Lifestart

- The maternal mortality rate (MMR) in India is 254 per 1 lakh live births (2004-2006), down from 301 in 2001-2003

- India has set itself an MMR target of 109 by 2015, which Unicef says the country will not be able to achieve

- India wants to see how Bangladesh brought down MMR

- Indian health officials will travel to Bangladesh to study that country’s intervention models

***

Despite efforts by the government to arrest the alarming maternal mortality rate (MMR) in India, progress has been very slow in the past few years. Outlook has now learnt the government is considering taking a leaf out of Bangladesh’s efforts at containing maternal mortality. India’s MMR is currently 254 per one lakh live births; the target is to take that figure to 109 by 2015. Unicef’s ‘The State of the World’s Children’ report released this year estimated that “78,000 women die from pregnancy and childbirth” every year in India and that the country was unlikely to achieve the 2015 target.

Amit Mohan Prasad, joint secretary in the Union ministry of health & family welfare, says, “The latest figures have shown that our MMR, which was 301 in 2001-03, has come down to 254 in the 2004-06 period. This is largely due to the success of Janani Suraksha Yojna (JSY), which is being seen as a success internationally.” The JSY, which falls under the umbrella of the National Rural Health Mission (NHRM), covers all pregnant women belonging to households below the poverty line and above 19 years of age for up to two live births. JSY integrates ante-natal care, institutional delivery with cash incentives and post-delivery care. “We are open to learning and exchanging ideas,” says Prasad. “Many countries want to adapt some of our intervention methods and we don’t mind studying theirs.”

In Bangladesh, the Australian Aid Programme in 2008-09 achieved positive results in decreasing maternal mortality rates in a pilot project. A 13 per cent decrease in MMR was achieved, from 254 per one lakh live births in 2007 to 221 in 2008 (compared to the national rate of 320). This is seen as a giant leap in checking MMR in Bangladesh. Indian health ministry officials will be travelling to Dhaka to study Bangladesh’s initiative in detail to implement them back at home. “Bangladesh has had very intensified efforts in the areas that record high MMR. Results only come from the betterment of the overall medical system. And since their health system is weaker than ours, we want to study the few things that caused this positive outcome and hopefully implement it,” says a health official.

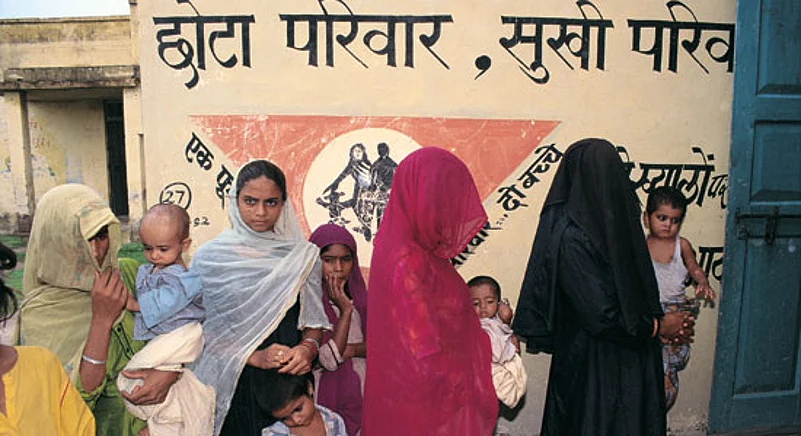

In India, efforts have focused on increasing the number of institutional deliveries in rural areas, spreading awareness on contraception and family planning and mobilising more skilled health workers. But it’s the cash incentives to delivering a baby in a hospital that have brought more women to hospitals. Prasad insists that since the project only started in 2005, the full results will only show in the next assessment. However, he did not want to comment on the chances of India failing to achieve its 2015 target.

For India, another struggle is against the huge gaps in the healthcare system from state to state. Two-thirds of all the maternal deaths in the country occur in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkand, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Assam. In these states, the administration of schemes has largely failed. Nepal, on the other hand, has made a giant leap, bringing down MMR from 540 to 280. This is being seen as a result of the legalisation of abortion in 2002. Also, Sri Lanka has the lowest MMR in South Asia at just 27 in 2002. A well-connected maternal healthcare system and a large number of institutional deliveries have led to these results. India could take a few tips from these countries too.