In the rich storytelling traditions of the patua scroll artists of West Bengal, there exists a version of the Ramayana that is distinct from all others. Unlike most other Ramayanas—even ones that are critical of him—Chandrabati’s version has perhaps irked Ramayana enthusiasts the most, as she spends no time eulogising Ram. Or critiquing him. Instead, she completely ignores him.

Her story starts with a river in Sita’s village and her miraculous birth. While maintaining some of the basic plot points, Chandrabati’s short, humble Ramayana in Bangla takes liberties that few Ramayanas of the time had taken. Not only does Sita tell the story herself, she also snubs the great war—the central theme of Ramayana, and dedicates few lines to it.

Instead, she chooses to add detailed episodes about both Sita and Rama’s birth, where she minutely describes the pregnancies of Mandodari and Kaushalya. The stories are told through a “Boro mashi”—a woman’s song about everyday sorrows. It’s as if she mentions Ram and the war, just so that she can tell the story of “Sita’s sorrows”.

ALSO READ: Who Is Ram And What Is His Story?

In her 1997 paper titled, ‘Rewriting the Ramayana: Chandrabati and Molla’, Nabanita Dev Sen noted that Chandrabati showed no interest in following any particular literary tradition. Her work did not aspire to be read and praised in the court of men. And it definitely wasn’t.

For the longest time, Chandrabati’s Ramayana was dubbed the worst Ramayana ever written. And there are at least 300 iterations of the tale of the God-King Ram. Chandrabati has been critiqued (mostly by male scholars) for her stylistic weakness, for her lack of mastery of the Sanskrit language, and for failing to stay true to the script.

Sen, however, posited that “Chandrabati’s Ramayana was rejected not because it was incompetently crafted or incomplete, but because it was not a traditional text. It is a woman’s text, an atypical retelling of the Rama tale in which Rama is first marginalised and then criticised from a woman’s point of view. In fact, Chandrabati’s Ramayana was never even properly read for what it actually was: the story of Sita’s journey from birth to death,” Sen wrote.

ALSO READ: Who Is Ram? Defining The Enigma

Chandrabati’s Sita would have been all but forgotten had it not been for the patua storytellers of West Bengal, who kept Sita’s story alive in their scrolls. And the songs of women’s everyday sorrows.

The discovery of Chandrabati’s Ramayana in the late 20th century by feminist scholars was a revelation for many Indian women and scholars, who went on to write their own versions of Sita’s story. These ‘feminist’ retellings of Ramayana often explore the various facets of Sita and try to tell the story of Ramayana through Sita’s perspective. They show Sita not as the tame, submissive “pativrata” wife who walks through fire with a smile on her face to prove her chastity to her husband, but as a fierce, even wilful woman with agency and sexual urges.

“As a woman, we are immediately drawn to other women characters, and so the idea of retelling normative texts from the perspective of women made sense to me since it directly affects the way women are expected to behave and be. And there are so many strong women in ancient Indian texts such as the Mahabharata, who have nevertheless been overshadowed by the male characters, becoming mute objects in the background,” Samhita Arni tells Outlook. She has co-authored Sita’s Ramayana, a graphic retelling of the Ramayana with patua artist Moyna Chitrakar. Arni, however, admits that in the beginning, Sita failed to excite her. “I was naturally more drawn to the Mahabharata. In contrast, Sita appeared very tame and submissive. And silent.”

And there was good reason for that.

In the 2,000 years since the Ramayana was first written by the sage poet Valmiki, the story of Ram and Sita have undergone many edits, omissions and additions. And much of it has to do with the way Ram treats Sita at the end of the tale.

The Maharashtra government, in 1988, posthumously published Volume IV of B.R. Ambedkar’s Riddles in Hinduism, which contained an article, “The Riddle of Rama and Krishna”, in which he noted, “Rama was not an ideal husband. His treatment of Sita was in fact extremely cruel. He even puts her through an agnipariksha and later abandons her in the forest, with no thought of the fact that she is pregnant.” It was just one of the many explosive statements made by Ambedkar on the popular perception of deified literary characters.

The essay led to a prolonged political offensive against it by the Hindu right wing, which claimed as always that such interpretations of the Ramayana were hurtful to the religious sentiments of the Hindus.

However, Ruth Vanita, author of The Dharma of Justice in the Sanskrit Epics: Debates on Gender, Varna, and Species, points out that Ram’s treatment of Sita has been over millennia one of the two most important narratives for Indians to discuss and criticise men’s and society’s treatment of women.

Vanita, who specialises in British and Indian literary history, adds, “Different Ramayanas have thus told the story differently, mostly with regard to the ending”.

In her seminal essay on Sita titled, ‘Rejecting Sita: Indian Responses to the Ideal Man’s Cruel Treatment of His Ideal Wife’, author and academic Linda Hess studied the way the trial-by-fire episode played out in different versions.

In Valmiki’s text, Ram asks Sita to undergo an agnipariksha to prove that she had remained untouched by other men. She passes the test. However, growing restless of rumours about Sita’s promiscuity proliferating through the kingdom, Ram decides to abandon Sita at a time when she is pregnant with his twins.

In fact, in some versions, Lakshman takes Sita to a forest and deserts her there without any explanation or parting words from Ram. These acts make Ram appear far from being the patnivrata maryada purushottam he is projected as by many.

The Tamil poet Kamban reimagines Ram as a romantic, with his version depicting more moments of conjugal bliss and togetherness between Ram and Sita. However, Kamban’s Ram is even harsher in his denouncement of Sita at the time of the “trial by fire” episode.

ALSO READ: Lesson On Environment From Ramayan

It was Tulsidas, however, who, in his retelling of the epic (known popularly as Ramcharitmanas, and the one adapted by Ramanand Goyal for the Doordarshan magnum opus) invented the definitive alibi to excuse Ram’s drastic behaviour toward Sita by introducing a trick that completely destroys the essence and originality of Sita’s own character.

He introduced the idea of ‘Chaaya Sita’, an illusory version of Sita that Ram had replaced the real Sita with, in the middle of the tale. At the time of the agnipariksha, Chaaya Sita goes back into the fire, while the real Sita comes out unscathed. Tulsidas’s Ramayana also cuts out entirely Ram’s derogatory words to Sita, referring only to some “harsh words”.

“Sita’s protest at the end, when she refuses to return to Ram and prefers to return to her mother, the Earth Goddess, powerfully raises question of injustice within the Valmiki Ramayana. The debate is so strong that the TV Ramayan had to include the episode of her exile and protest on popular demand,” Vanita points out.

The changing of Ram’s attitude towards Sita also meant that Sita herself changed through the retellings. In the Valmiki Ramayana, Sita expressed her outrage and protested against Ram’s behaviour during the trial-by-fire, and showed agency in ordering Lakshman to build the pyre for her to self-immolate in protest.

In Tulsidas’s Ramayana, Sita’s protest goes missing and she is almost confident and happy before stepping into the flames. As Hess points out, “As there is no cruel speech by Ram, there is no outraged rejoinder by Sita either. Sita becomes more silent.”

In the past centuries, many authors, academics and feminists have tried to give Sita her voice back, and “feminist” retellings of the Ramayana abound through the vast oeuvre of Ramayanas, much before the word “feminism” was globally perceived.

In tribal retellings, for instance, in what is now the Chota Nagpur plateau region, Sita has often been seen as the embodiment of an agrarian expert and nature warrior who brought prosperity to her “father” Janak’s land, making her deeply rooted to their relation with their land.

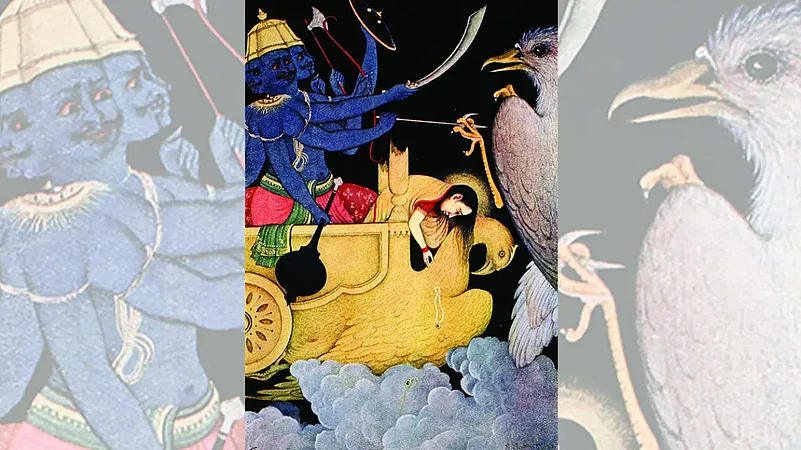

Valmiki himself chose to re-imagine Sita as a powerful force in Adbhut Ramayan, in which she takes the form of Kali and unleashes vengeance upon earth. It is she who kills Ravan, not Ram.

“I have written about the 15th-century Sanskrit-language Adbhut Ramayan, which shows that Sita, the Goddess, is more powerful than Ram and defeats a more powerful Ravan in battle; Ram ends up worshipping her. But she chooses to play the role of the less-powerful wife in the story as we know it,” Vanita tells Outlook.

Gond Ramayani, a series of seven tales that begins after Sita’s rescue in the Ramayana, tells the story of Lakshman, who is made to go through a trial by fire to prove that he was not infatuated with Sita. In fact, the relationship between Sita and Lakshman has several significant variations in regional or tribal Ramayanas.

In one such attempt to rewrite Sita’s history, Snehalata Reddy, in her 1973 one-act play Sita, gave the titular heroine a powerful voice that asks questions many have echoed before and after her: “I am not afraid of death, Lakshman, but I’m afraid... of this awesome male domination and the helpless, pathetic and unbelievable martyrdom of women (in the name of dharma).”

Which brings us back to the question many have asked over the centuries: was the Ramayana unfair to Sita? Ruth Vanita does not think so. “A literary text is not “unfair” to anyone. It merely tells a story and raises questions,” she points out. “People are unfair to each other.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "Being Sita in a Man’s World")