The Angry Hills

- NSCN(I-M) chief T. Muivah, coming home after 40 years, is stopped from entering Manipur

- State government fears resurgence in the Greater Nagalim struggle

- Manipur under ‘economic blockade’, protests rip through state

- If stalemate continues, NSCN(I-M) threatens to “go underground” again

***

“It’s do-or-die for us. We will sacrifice our lives for our leader,” a young boy stoically told us before merging into the crowd of men, women and children gathered at Mao Gate at the Manipur-Nagaland border on a sunny morning earlier this month. It’s not clear if, moments later, as they charged in through the barricades, amidst the teargas shells, stone pelting and firing of gunshots, it was he who died along with another Naga student. But what is clear is that, in an inversion of the ancient tale of Helen of Troy, in which a city burnt because one woman would not go back home, two Indian states are on the verge of bursting into political fire because one man cannot.

Thuingaleng Muivah, the 74-year-old general secretary of the separatist National Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isak-Muivah)—NSCN(I-M)—is no Helen of Troy. He is a man, a plain one at that, and the son of poor peasants. More importantly, he’s driven not by romantic love but by the fire of identity politics. In the last few days, he has certainly demonstrated that he still has the fire, generating mayhem while engaged in a quest that is both intensely personal and political—to find a way back to his ancestral village, Somdal, after a gap of nearly four decades.

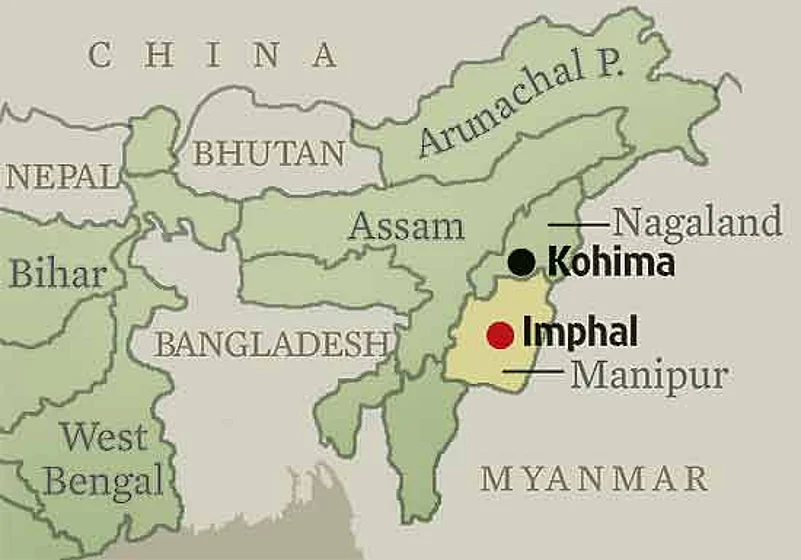

Trouble started immediately after the NSCN leader announced his plan to visit Somdal, situated in the remote hills of Manipur, earlier this month. While the Centre, which has had an intermittent ceasefire deal happening with the NSCN since 1997, gave its nod, in Manipur, Muivah’s proposed visit to the Naga-dominated region immediately raised the spectre of Greater Nagalim (the NSCN’s desired Naga homeland, which includes large parts of present day Manipur). The Manipur government’s official spokesperson, N. Viren, baldly told Outlook earlier this week, “Muivah stands for the disintegration of Manipur and Manipuris do not want him here.”

So there was bloodshed as Muivah’s supporters clashed with the Manipur police at the border; then came a Naga-imposed ‘economic blockade’ on Manipur. Transport routes to the state pass through Nagaland, and even essential commodities weren’t going through. In between, the seven Naga legislators in the Manipur assembly resigned in protest against the ban on Muivah. “The situation is grave,” Viren told Outlook. “The prices of food and other essential goods have skyrocketed. Even life-saving drugs are not reaching hospitals.” With the crisis spiralling, the Centre initiated a series of moves to end the stalemate. The Nagaland and Manipur CMs were summoned by the PM, top central ministers visited the two states. But to little avail.

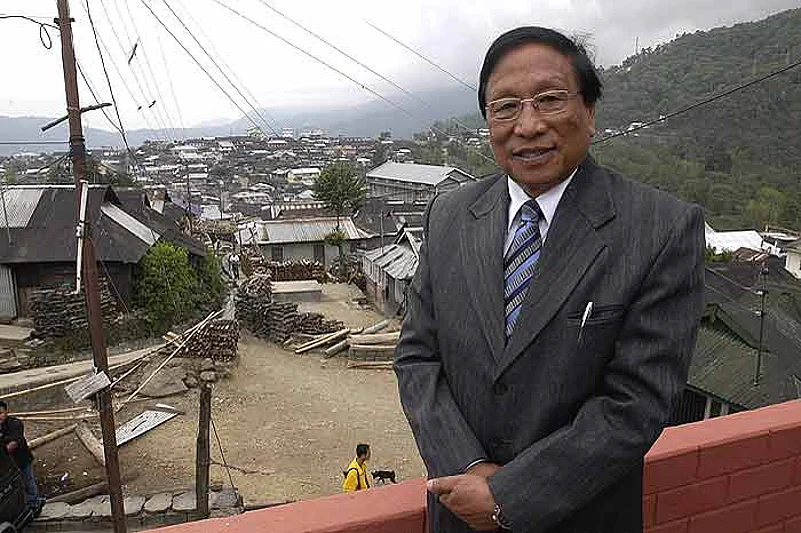

Meanwhile, the man over whom all this ruckus has erupted bides his time at the little hamlet of Viswema on the Nagaland-Manipur border, “until”, he tells Outlook with an air of quiet understatement, “things are a little calmer”. We meet in a house atop a hill, after climbing up a winding set of stone stairs guarded by Kalashnikov-bearing sentries. Muivah stands at the edge of the terrace, looking out into the horizon...a vista of blue mountains, covered in grey mist. He looks patient rather than perturbed, determined rather than dismayed.

Naga protestors block NH-39, Manipur’s lifeline

He changes from casual clothes into a formal suit for the interview and photo-session, explaining that he wants to look neat. Statesmanlike, perhaps, is what he means. “I’m human too,” he says, when we ask him why he wants to go home. “When my parents died, I could not be with them. I want to visit their graves.” In conversation, he refers frequently to his mother, whom he calls “Mummy”, and says he “misses” her terribly. In a more political vein, he adds: “She instilled in me the value of an identity.”

The Meitei-Naga conflict is at the heart of the current stand-off and, not surprisingly, if Muivah is to be drawn out, it is on this subject. The Hindu Meitei community, which politically dominates Manipur, treated the Christian Nagas as “untouchables”, Muivah remarks. He says he has to this day not forgotten the sting of a Meitei insult. “I was in Class 3 at the time. My parents had taken me to work in the city on a road-construction project. My employer refused to shake my hand. He said for a Naga, it was audacious of me. I felt humiliated.”

Muivah uses incidents like this to explain, and justify, the quest for a separate Naga identity. It’s difficult to imagine that the friendly, gentle man sitting across the coffee table was, less than two decades ago, on the Indian government’s list of “most wanted” terrorists. That this man has spent a large chunk of his life out in the wild jungles stretching from India to China through Burma and other parts of Southeast Asia, leading a guerrilla army once referred to as the “most dreaded insurgent outfit” India had ever confronted. That there was once a price of Rs 1,00,000 on his head—an official notice that, incidentally, is yet to be formally revoked. That he has travelled the world on fake passports until he was caught one time by immigration officials at a Thailand airport (he made an unsuccessful attempt to escape from the country by jumping bail). For his fervour, he’s suffered a host of physical injuries too, even had teeth knocked out in a brush with the Indian army. He has also, “as per the compulsions of guerrilla warfare”, ambushed, yes, shot dead “the enemy”, but never, he insists, “innocent civilians”.

So has the man mellowed with age? Is his visit really as apolitical as he and his followers say it is? Or is there a “more dubious design”, as Manipuris firmly believe. “If this is only a personal visit,” Viren asks Outlook, “why did he have meetings planned in various venues across Manipur?” We ask Muivah, why now after nearly 40 years? “I think there is a season for everything,” he says. “I’m old. I couldn’t come home all these years because we were underground.”

It’s not clear, at this point, how the current stalemate will be resolved. But one thing is for sure: the stand-off has only added to Muivah’s stature among his own people, even though he is a remote, somewhat inaccessible figure for most of them. Outside Muivah’s house, an NSCN leader tells us, “The ceasefire can go to hell. We are ready to go underground over this issue.” Hopefully, it will not come to that again.