On Tuesday, December 7, a scrum of over 50 British and international journalists were crammed into court number one in the Westminster magistrates court, central London. There were TV crews from Japan and Algeria, print reporters from Russia, a radio team from Spain. Outside, the scene seemed straight out of a showbiz trial—Pete Doherty nabbed with drugs, Paris Hilton caught driving over the drinking limit, Tom Cruise suing someone. One passerby asked, “Who’s in there?” A photographer cleaning his lens answered, “WikiLeaks bloke.” The passerby sighed, “Aah.”

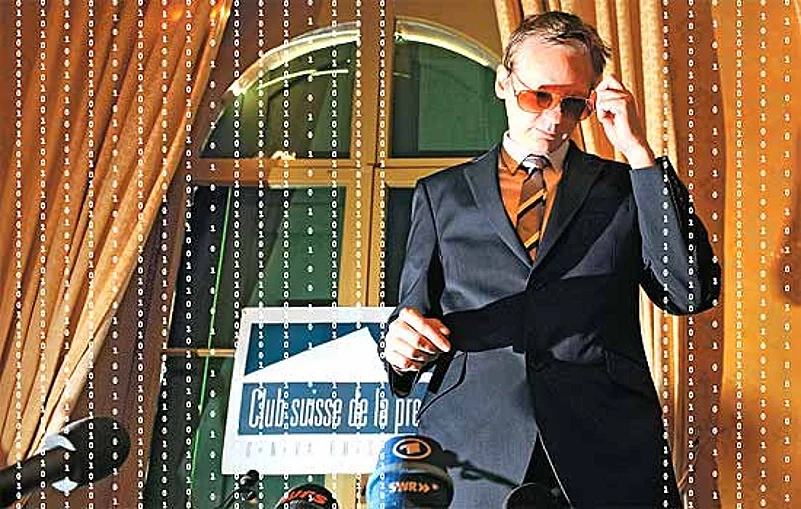

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is indeed a celebrity now, with a global footprint, his face recognised everywhere, his name giving the jitters to powerful world leaders and evoking a range of responses among common folk—from admiration to exultation to confusion and scorn. His fame spread far and wide from the time the United States deployed its formidable power to launch an international operation to prevent the WikiLeaks website from releasing some 2,50,000 diplomatic cables that American embassies worldwide had sent to their headquarters in Washington. Unable to sabotage Wikileaks or stem the release of cables shared with five media outlets—the Guardian, the New York Times, Le Monde, El Pais and Der Spiegel—America and other western countries then sought to at least temporarily incarcerate him, to set him up as an example for audacious netizens daring to challenge powerful governments.

.jpg?w=801&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&dpr=1.0)

The hunt for Assange began soon after Interpol released an arrest warrant on November 20, based on the sexual assault charges two women, Anna Ardin and Sofia Wilen, had filed in August in Sweden. Tired of shifting from one hideout to another to evade the police, Assange surrendered and was brought to the court on the same day for bail hearing. During the court proceedings, the following charges emerged against Assange—that he apparently continued to have sex with Anna even when his condom came off and she wanted him to stop; that he coerced her into sex on another occasion by “using the weight of his body to pin her down”; and that he allegedly had sex with Wilen while she was sleeping.

.jpg?w=801&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&dpr=1.0)

| Bitter Swedes Sofia Wilen and Anna Ardin file charges |

Is Assange a cyber-Osama then, using deadly firepower, albeit of the technical kind, to embarrass and hurt the mighty United States to achieve his ideological goal? And what is Assange’s goal? Is he an anarchist relishing the discomfort of the powerful? Or a poster-boy of post-modernists seeking a new, transparent way of governance? Steven Aftergood, who directs the Federation of American Scientists project on government secrecy, feels the indiscriminate use of the word terrorism has drained much of its original meaning. “It’s possible,” says Aftergood, “to see WikiLeaks as an anarchist enterprise that stands outside of existing structures of power and authority, practising a form of coercive transparency that disregards the security and privacy interests of nations and individuals.”

Yet, the narrative woven around bin Laden has various tones and shades, each signifying different meanings to different people and nations. It’s the same with the WikiLeaks founder. Like Osama, Assange is a non-state actor whose turf is not a country but the whole world. Again, both seem to derive immense pride and pleasure out of opposing the world’s only superpower. Osama and Assange’s rhetoric harps on the hypocrisy of the powerful; both deftly exploit the mass media to spread their message. Neither commands a large organisation—the WikiLeaks team is said to consist of a total of seven members—and are dependent for their efficacy on volunteers who are attracted to them for their charisma and spectacular feats. Both seem to expand their following even as the attacks from the US gain in ferocity. And, finally, both sanctify their actions in the name of trying to usher in a just and humane world order.

Leave Osama aside. Assange and a just order, is that a contradiction in terms? In a way, Assange’s philosophy is aimed at transforming institutional behaviour, rendering it more transparent. The New Yorker’s Raffi Khatchadourian spent days with the man in his “secret bunker” when he was preparing a video release of the Apache helicopter attack on innocent Iraqi civilians. Raffi wrote, “Assange...emphasised...his mission is to expose injustice, not to provide the even-handed record of events. In an invitation to potential collaborators in 2006, he wrote, ‘Our primary targets are those highly oppressive regimes in China, Russia and Central Eurasia, but we also expect to be of assistance to those in the West who wish to reveal illegal or immoral behaviour in their own governments and corporations’.” He also believes, says Raffi, that a social movement to expose secrets “could bring down many administrations that rely on concealing reality—including the US administration”.

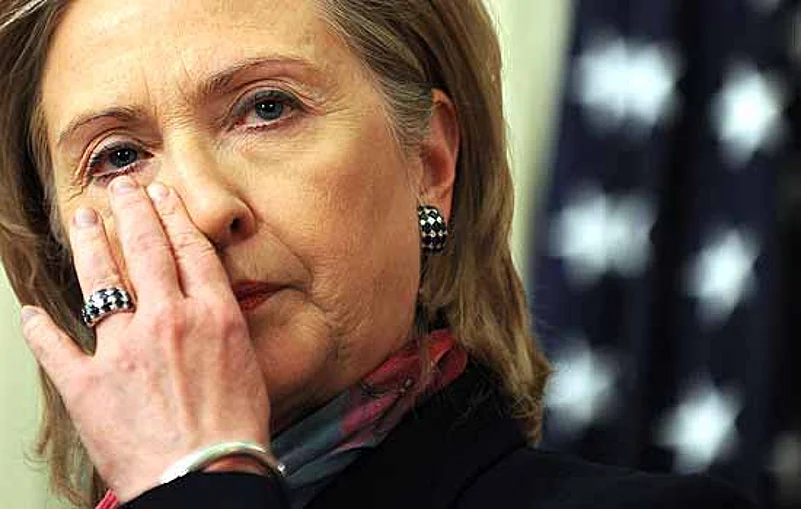

US SOS Hillary Clinton warned of leaks affecting ties

Assange articulated his philosophy through the Apache video. It opens with a quote from George Orwell that Assange had selected—“Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give the appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Weaned on Kafka, Koestler and Solzhenitsyn, Raffi says Assange defines human struggle “not as left versus right, or faith versus reason, but as individual versus institution”. An excerpt from an essay he wrote in 2006, the year in which WikiLeaks was founded, bears out his antipathy to regimes and gargantuan institutions. “To radically shift regime behaviour, we must think clearly and boldly, for if we have learned anything, it is that regimes do not want to be changed. We must think beyond those who have gone before us and discover technological changes that embolden us with ways to act in which our forbears could not.” In this remark you can well see the blueprint of what WikiLeaks was to become—a secret-busting, whistle-blowing website involved in exposing the dark side of governments, ruffling the world’s powerful and rich in America, Asia, Europe and Africa.

In such a scenario, the powerful, unaccustomed to challenges, were bound to retaliate. True, a range of world powers have taken a terrible hit. Says Julian Borger, diplomatic editor at the Guardian, “It depends who you talk to, the Americans are very upset and braced in anticipation of what will come out. It’s a terrible blow for them in terms of confidentiality and ability to do their work and whether people will trust them in the future when they talk about anything that requires confidentiality.” Yet embarrassment doesn’t justify the hounding of Assange, whose leaks of cables certainly don’t threaten anybody’s life. As Dr Premen Addy of Kellogg College, Oxford University, says, “If anyone’s life is at risk, it’s because the US government went to war on two fronts and caused mayhem. Instead of addressing that, they are running after who did what on WikiLeaks.”

| “It’s a coercive transparency that disregards privacy and security interests of nations and individuals.” S. Aftergood, Project director on government secrecy |

| “If anyone’s life is at risk, it’s because the US government went to war on two fronts and caused mayhem.” Premen Addy, Kellogg College, Oxford University | ||

| “It’s a kind of joke, isn’t it? (But) leaks of this kind will reduce institutions to employ PRspeak all the time.” Claire Fox, Director, Institute of Ideas, UK |

| “What’s coming out of WikiLeaks is potentially good for democracy. But it’s also potentially lethal.” Dr Vittorio Bufacchi, University College Cork, Ireland | ||

Assange’s supporters claim the legal sideshow in London is simply a crude method of gagging him. Jo Glanville, editor of the UK-based Index on Censorship, says the retaliation against WikiLeaks reeks of hypocrisy and selective targeting. After all, nobody has threatened to take action against those in the print media who are co-publishing the WikiLeaks cables. Adds Stephen Kohn, executive director of Washington’s National Whistleblowers Center, “They have declared WikiLeaks Public Enemy No. 1. There’s clearly no proportionality here.”

Others like Todd Gitlin of Columbia University, though, think WikiLeaks “has made it more difficult to conduct diplomacy, which is a necessary function of governments—all governments”. Diplomacy, as we all know, requires immense patience and time—governments talk to each other for years before reaching an agreement; there are harrowing negotiations and bargaining not immediately intelligible to people, and leaders often do reach secret understandings to bring to reality a larger vision they have in mind. Hence, the question: should every aspect of diplomacy, or governance, be shared with people?

Perhaps this is why the cables furore has split the commentators more sharply than WikiLeaks’ two projects pertaining to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The leaked cables haven’t as yet highlighted human rights abuses, prompting Claire Fox, director of the Institute of Ideas, a UK think-tank, to quip, “Well, it’s a kind of of joke, isn’t it?” Really, she asks, would you be interested to know trivia such as Libyan leader Gaddafi’s fondness for botox? But the judgement on the cables depends on your perspective, even on where you are located. To those in the West, it might seem mere gossip to know that members of the Saudi royal family love to drink and party hard, but to most Arabs it’s a story with immense political undertones. Again, the WikiLeaks expose of the doublespeak of leaders in Pakistan might not astonish citizens of other countries, but it has outraged citizens there.

Claire, however, attacks Assange’s philosophy. “He has made the point that the new politics is the individual against institutions which are involved in a big conspiracy that needs to be unravelled. This kind of approach is incredibly dangerous. Leaks of this kind will reduce institutions to speak in PR language all the time.” The riposte of Dr Vittorio Bufacchi, lecturer in philosophy at University College Cork in Ireland, is quick: “What’s coming out of WikiLeaks is potentially good for democracy. But it is also potentially lethal—it all depends on the nature of the leaks.”

Democracy, Dr Bufacchi says, demands transparency and openness, a condition that is necessary for people to repose faith in those commanding authority. And nothing is a better deterrent to all the bad practices of democratic politics than public exposure. Dr Bufacchi, however, warns, “It would be naive to deny that on the international stage liberal democracies are under threat from non-liberal and non-democratic forces. In this struggle for world supremacy, knowledge coming out of WikiLeaks could be used to discredit, if not undermine, the appeal of liberal democracies. If that were to happen, things could get serious.”

Few, though, deny that WikiLeaks, as also the internet, has changed the rules of the game—in politics, journalism and diplomacy. As Borger says, “previously a journalist could probably hang a career on obtaining five or six cables like WikiLeaks, let alone access to 2,50,000. It definitely changes the landscape of what we do.” And for all this, we perhaps owe a token of gratitude to Julian Assange.