The memories of those who lived in Bombay, before it became Mumbai, the bustling, overpopulated megapolis, are intricately connected to a labyrinth of congested streets with tenements known as chawls. Amol K Patil, a performance artist, owes his artworks to his roots in these chawls where he was born and raised. 36-year-old Patil studied visual arts from the Rachana Sansad Academy of Fine Arts and Crafts and is the initiator and participant of several collective practices and exhibitions around the world since 2013. His work takes the viewer through the multiple media that he works with—performance art, theatre, music, kinetic art and video installation.

Taking inspiration from his life in the chawl, Patil embarked on the project ‘What is Human Becomes Animal’, which brought to life the situations faced by sanitary workers in Mumbai, the conditions they worked in and the caste discrimination they have faced and continue to face today. Arguing that their work conditions and the daily degradation they face are beyond inhumane, ‘What is Human Becomes Animal’ foregrounds socio-economic discrimination and inequality. Patil also looks at the growth of Bombay into Mumbai, an overpopulated megapolis where the workers are dwarfed by the scaffolding of centralised urbanisation.

Patil’s father was a Powada Sahir—a theatre artist, interpreter and poet who went from one village to another, telling stories from the epics and addressing various social issues such as the devastating effects of immigration and its traumas. Reefing through old cupboards in his family home, Patil discovered an old dicta tape-recorder, a Walkman and cassettes that captured sounds of immigrant dialects that his father may have recorded. Patil used these recordings as part of his work, ‘Afterglow’, exhibited at the Yokohama Triennale in 2020. Patil also found theatre scripts showcasing the dilemma of a migrant’s life in the then Bombay and handwritten songs of his grandfather—also a Powada poet.

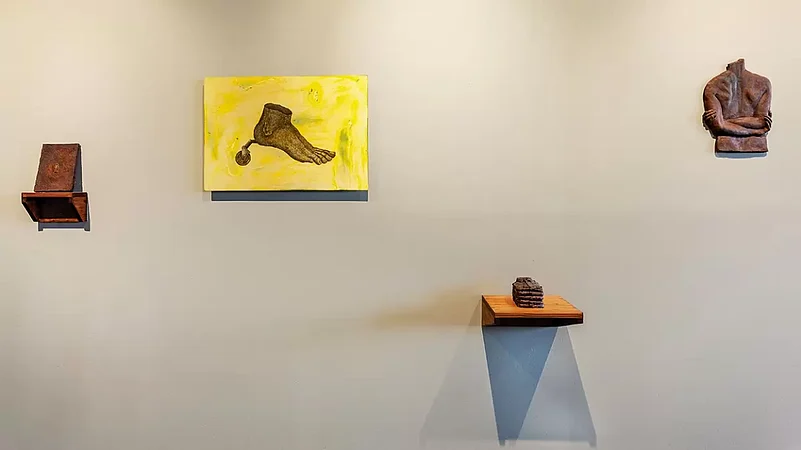

At Kochi, Patil exhibited his kinetic work ‘The Politics of Skin and Movement’ which explores the idea of movement, motion and life. The artist speaks to Haima Deshpande about the numerous events and people that have shaped his perspective as a person and as an artist.

There is a lot of emphasis in your art on the Dalit community and the jobs they do. Could you elaborate on your interest in the subject?

The initial engagement with the subject began with a solo show that happened in 2013. The main premise of the show was based on Marathi theatre, after which I started looking at the archives of my father and grandfather.

Looking at the generational archives of two different time periods helped me a lot in developing an understanding of the Dalit community. I started visiting the locales and having conversations with the people of my generation —locals, friends and neighbours. That also molded my understanding about the community and its structure.

The realization that came to mind was the existence of a silent conversation in our everyday life about casteism—in government offices and so on. I use these themes and subjects in an attempt to open up spaces of interactions for people to access these conversations, these missing histories and to also bring up a futuristic conversation about change and resistance in everyday action.

Chawls have been a central theme in your works…

I grew up in an area of chawls which is specific to Mumbai and is basically a form of social housing for factory and mill workers built in the early 1900s. The reference to chawl architecture and the habitus in the practice comes from these memories and experiences.

Could you describe the themes used by your grandfather and father in their artistic practice?

My grandfather was a poet and my father was a theatre artiste. Going back through the archives of these histories, I found cassettes filled with sounds and dialects of my father which he had recorded for his theatre scripts. I also started reading poems written by my grandfather which included songs from a protest tradition which has continued since the 17th century. These songs are called ‘chawda’. These archives had a strong impact on my understanding of the Dalit community.

Your kinetic installations are always very popular...

People are quite curious about the kinetic installations since as a whole they appear as a still image. However, on a closer look one can see subtle movement. These subtle vibrating movements make the experience more engaging for the viewers.

How do you perceive the impact your works have on your viewers?

The impact differs across different spaces and its interactivity with people. Like in India, different questions arise about how a generation is looking over a time period of local histories.

In terms of the formal aspects, the audience try to connect with the subtle movements of the kinetic installations. That way, the viewers also embody these movements and become a part of the experience. I like the play of subtle humour in the art works. Also, it is always a pleasure to see the interaction of the people with the kinetic works and their different reactions.

What is the message your work intends for the viewer?

Through my practice I try to bring into conversation the issue of the missing archives of the Dalit community such as looking into the everyday lives of the community living—the way the young people of the community do the work of cleaning along with their theatre practice. The works also opens up a discussion to think about these situations in a futuristic way. Basically, the work makes it possible for a larger audience to access these archives.

(This appeared in the print edition as "And The Archive VIBRATES")