The recent disaster in the Seraj region of Mandi district, Himachal Pradesh, exposes an unsettling reality: the current development model in the Himalayas is proving disastrous, unrealistic, and even risky.

The fragile mountains, which are already the most vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather events, are being pushed to the brink by a pattern of reckless construction and unplanned infrastructure projects, highways and power projects.

The so-called development may serve the short-term interests of a few chosen ones or political ambitions, even tourism activity, but it comes at the irreversible cost of community safety. The long-term sustainability of the people, whose co-existence with nature and mountain ecology has never been threatened, is currently at risk.

This is not the first time that Himachal Pradesh has witnessed a calamity of a massive scale, confined to one particular high mountain belt, which until 1990 was highly underdeveloped and riddled with poverty. Lack of road connectivity and poor health, education, and drinking water infrastructure have kept the region deprived for years. Many families struggled hard and also picked up labour and daily wage jobs, outside the area. But now there is a notable transformation on the ground.

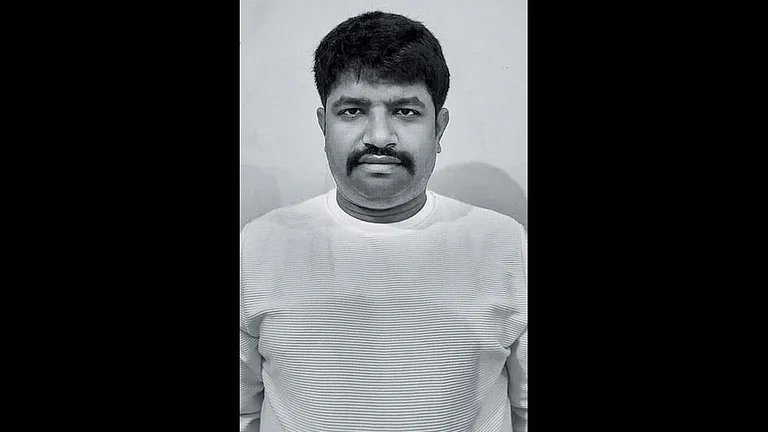

Former Chief Minister Jairam Thakur, now a sixth-term MLA from Seraj, recalls how his father, a mason, sustained the family.

“I would walk nearly nine kilometers each way—up steep mountain terrain—to attend school. Back then, there was hardly any sign of development. Since there were no roads, we spent our childhood dreaming of the day we could ride a bus. Access to basic healthcare and higher education facilities was also a distant dream.

Yet, the self-sustaining farm economy remained the backbone of the community's lush green forests and natural water streams.

But now, after five years of his chief ministerial stint, Seraj presents a picture of faster infrastructure growth, fruit property, developed markets, construction, and unaccounted health and educational institutions, even tourism projects worth hundreds of crores, also funded by ADB (Asian Development Bank).

Manshi Asher, an environmental justice activist, admits that Seraj is a region that has seen substantial development both in the expansion of the road communication network and new constructions in a short period during the Chief Ministerial tenure of the region’s MLA, between 2017 and 2022, and then also from 2022 to 2025.

“Facilities that come up, including in the health and education sectors, besides road connectivity, may be very important for the region. Yet it appears to have been rushed and unplanned for political reasons,” she underlines.

Truly so, such fast-tracked development, markets, and infrastructure-building activities in the ecologically fragile region without assessing the vulnerability of the sites can't be safe. The entire anthropogenic activity, indiscriminate disposal of the debris along catchments, and natural drainages contributed to the devastation.

Retired bureaucrat Tarun Shridhar, who had also served as Deputy Commissioner of Mandi, says frequent and increasingly severe disasters in Himachal Pradesh are the result of multiple factors. The state’s vulnerability to the environment and climate change, and the impact of global warming, are the biggest triggers. Yet, it’s more likely to be attributed to pervasive and unsustainable anthropogenic activities.

Here, he claims the time has come to debunk the phrase “natural disaster” because the fatalities and devastation caused by the extreme weather conditions—floods, cloudbursts, landslides, and house collapse—have more to do with haphazard development dictated by populism.”

In 2023, the monsoon wreaked havoc on the Kullu and Mandi districts as never before. Torrential rains, flash floods (in Beas), and landslides paralysed normal life for days, disrupting road communication, electricity, and water supplies. More than 500 people died. The loss as a result of the calamity was assessed at over Rs 10,000 cr.

The state’s PWD minister, Vikramaditya Singh, went on record to blame the state administration for not controlling massive mining activities in the riverbeds and building giant properties like hotels and commercial properties along the Beas River. The public infrastructure, as a result, bore the toll. The floods left the state completely ravaged.

The National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) is building four-lane projects that have felled thousands of trees, involved large-scale cutting of the mountains, and dumped the debris indiscriminately.

Even in Seraj, the hill cutting, muck dumping, and deforestation to build public infrastructure also played a significant role in the disaster. Thus, disasters have been a round-the-year phenomenon in the districts of Mandi, Kullu, Kinnaur, Sirmaur, and Chamba.

According to Surjit Radhawa, a former principal scientist at the HP Council for Science, Technology, and Environment, the topography of Seraj is quite peculiar. The areas, though, had been witnessing cloudbursts and monsoon rains even before. But destruction of this scale can’t be attributed to climate factors alone.

“Cloudbursts are a recurring phenomenon in mountainous regions. While specific meteorological conditions contribute to these events, intense convective activity is often a key trigger,” he explains. “However, the scale of devastation, as happened in Seraj, is significantly amplified when traditional flood channels are obstructed, debris is recklessly dumped on fragile slopes, and hill cuttings are carried out without scientific planning or regulatory oversight.”

He admits that it could be a wake-up call for the government to think of some alternatives to the development pattern and get a proper vulnerability study done on the areas before taking up any new activities or granting approvals to infrastructure projects.

Former Chief Minister Jairam Thakur, who has been camping in the area ever since the tragedy and has reached out to affected families, says it's wrong to condemn the development that happened at his initiative to meet the needs and aspirations of the people, who had lived in deprivation of facilities for years.

“There is an urgent need to investigate how not just one or two, but as many as 10 to 11 cloudbursts occurred within a brief period,” he urges. "Intense rainfall initially battered the region, followed by a series of powerful cloudbursts," recalls Jairam Thakur.

Moreover, the combined impact of flash floods and relentless rain created a catastrophic situation, leaving people helpless in the face of nature’s fury. Many families watched in horror as they lost their loved ones—some even while attempting to escape. Homes were inundated and stood no chance against such an overwhelming onslaught.”

It is essential, as Manshi Asher emphasises, to undertake a thorough assessment of the demographic and socioeconomic profile of the communities affected by the disaster. These populations, already vulnerable, now face compounded risks that demand urgent and thoughtful intervention.

She feels, “Policymakers and authorities must prioritise the development of a robust, need-based disaster response and rehabilitation framework—one that is shaped through direct consultation with the impacted families to ensure relevance, equity, and long-term resilience.

The larger question remains: who truly benefits from development—and at what cost?