When Veerendra—a famous Punjabi actor and cousin of legendary actor Dharmendra—was shot dead at the sets of Jatt Te Zameen on December 6, 1988, the Punjab insurgency was at its peak.

Though his murder remains a mystery to date, Preeti Sapru, a Mumbai-based actress, director, and producer, who was the slain actor's co-star, recalls that the incident left the Punjabi filmmakers shell shocked.

Undeterred, Sapru made sure the Punjabi film industry didn't die at the hands of militancy. She mortgaged her jewellery to raise money for Qurbani Jatt Di which released in 1990. Besides writing and directing, she played a double role in the film. While the star cast included Dharmendra, Raj Babbar, Gurdas Mann, Yograj Singh and Mehar Mittal, the famous singer Sukhwinder Singh composed its music.

Almost 23 years later, Sapru is elated over the worldwide release of her upcoming movie Teri Meri Gall Ban Gai but seems concerned about a strange paradox. “There is still an overflow of the movies. We need to learn from Telugu cinema, and produce quality movies,” Sapru tells Outlook.

Although this leading lady in Punjabi cinema with a few Hindi films to her credit was the first to introduce singers as protagonists in Punjabi movies, she says that the monopolies of a few singers have started to dominate the industry. The actor-director had cast Hans Raj Hans, a BJP parliamentarian, and Malkiat Singh in Mehndi Shagna Di (1992).

Sapru observes, “Now what is happening is that the singers are promoting themselves through their film companies instead of helping the medium to evolve into a vibrant industry. At present, what’s required are collaborative efforts by well-intentioned filmmakers, producers, distributors, and actors.”

Punjab cinema, which dates to British rule in India, produced the first sound film, Heer Ranjha, in 1932. Since then, several Punjabi movies have earned international recognition and the industry even gifted Bollywood with remarkable talent. While the industry was hit hard by the pandemic, Sapru and many other new-age filmmakers have high hopes that the industry will soon bounce back.

Before becoming a parliamentarian and then chief minister, Bhagwant Mann worked in Punjab’s entertainment industry. Mann recently warned Punjabi singers who glorify gun culture and drugs. But this was not the first time that a Punjab chief minister expressed concern over the industry people's alleged obsession with underworld traits. His predecessors such as Charanjit Singh Channi and Captain Amrinder Singh too had raised such concerns.

While Channi proposed a law to stop such music and movies, Capt. Singh had ordered a special drive to check such video and audio clips. On one such drive in 2020, 509 public buses were scrutinised and 212 were challaned. Incidentally, it was during Singh’s tenure that Punjabi singer Shubhdeep Singh Sidhu (Sidhu Moose Wala) was booked for promoting violence and screening of the movie Shooter, reportedly a biopic on the notorious gangster that then got banned. In the last state assembly election, Sidhu unsuccessfully contested on a Congress ticket.

However, Paramjit Singh Judge, former president of Indian Sociological Society and a professor at Guru Nank Dev University, is agitated over politicians and the “moral custodians of society” for stereotyping Punjab film and music industry.

He adds, “Artists have every right to express themselves as long as they don’t violate the law of the land. But there is nothing unusual shown in Punjabi that is not part of the popular culture in the rest of the country. How can we ignore violence in the name of religion? Marijuana is considered as Shiv ji ka prasad. Why isolate Punjab on this account? We have literature as old as 600 years that glorifies violence and nasha (intoxicants).”

He asks, “If depicting violence were to be banned, how one would stay off Sarbloh Granth, which includes worship of the sword? There's a sect in Sikhism that glorifies it. There is a whole tradition of singing in Punjab which is called ‘Vir Gatha’. In almost every Indian society, there is a tradition of singing about war, bravery, valour, and a particular tradition of violence.”

Saying that violence and valour are universal in nature just like sensuality, Judge asserts that Punjab should not be excluded and shamed.

“These politicians should stay away from the cultural sphere,” he says, citing the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution. He adds, “Some people started talking about proletariat culture and proletarian cult. Lenin had to intervene and stop it. But we have totalitarian regimes that dictate what one must do and what one doesn’t have to.”

He further points out, “Look at the Hindutva groups digging out stories of warriors. When we talk about this at a micro level, we are talking about domination and conflict.”

On whether violent songs and movies make people violent, the professor points at Japan, saying, "That country produces more violent films, but their society is largely peaceful.”

Pali Bhupinder Singh, a film director and professor at Panjab University, calls chief minister Mann’s comments as “unfortunate and misplaced”.

Quoting lyrics of a Punjabi song, Jailan de Bichchon Phone Aange, Singh says, “One can’t blame the writer or singer for such a song. The song doesn’t promote violence. It only talks about a larger issue that jail authorities should be concerned about. Unfortunately, artists are always soft targets. When a big political leader walks on the road, he is always surrounded by 30-40 gunmen. I think this practice promotes violence as they inspire awe in people.”

Arguing that there was nothing unusual that was shown in Punjabi movies when compared with Hindi films, Singh goes on to say, “We usually make movies on marriages, interpersonal relationships or slapstick comedies.”

Both Sapru and Singh feel that Punjab entertainment industry has a potential to generate massive employment and revenue for the state government. According to them, the state government should develop a film city and encourage Punjab film and music industry in every possible way through a concrete policy.

Discussing successive Punjab state government’s apathy towards film artists, Sapru adds, “Barring the exception of Dara Singh, Punjab government couldn’t get Padma Shri to any other reputed artist working for Punjabi cinema. It is really painful for us.”

While lauding chief minister Mann’s association with the Punjab film industry, Singh, whose movie Gurmukh: The Eyewitness is scheduled to be released worldwide in two months, says, “We have genuine expectation that he will promote Punjabi entertainment industry. The immediate steps that need to be taken with the government's backing include developing Mohali—that already houses more than 50 studios—as a film city.

“We need a separate censor board at Chandigarh just like other film industries in South India. We must get our movies cleared from Mumbai and it's non-Punjabi speaking officials. The Punjabi filmmakers' union must get a status of quasi-judicial body. In many states like Maharashtra, the theatres must allot one show to a regional movie on a daily basis. This needs to be made a norm in Punjab, as well increase efforts to promote Punjabi films.”

Many industry insiders believe that unthinking adherence to the outworn ideas plague Punjab cinema.

“No doubt the industry has seen tremendous improvement in production quality and expansion of distribution networks in recent years. But most of the movies still revolve around old subjects that reinforce the regressive value system,” says Daljit Ami, a noted writer-filmmaker and director of Educational Multimedia Research Centre, Punjabi University at Patiala.

While comedy is the mainstay of Punjabi cinema, Ami says most of the movies bring out a brand of comedy "previously confined to the gatherings of men’s cocktail parties". Such comedy promotes "unevenness" in the society.

Ami notes, "The argument we get to hear is that the audience wants this kind of content only. But the issue has another side to it. Cinema primarily caters to those young people who experiment with all kinds of intoxicants and perform several misadventures. But society takes responsibility in every possible way. Therefore, their argument shows only a lack of social commitment on their part.”

On the other side, Ami adds national award-winning filmmakers like Rajeev Kumar have touched upon socially relevant issues, saying “Just before the pandemic, he shot Chamm (2017) that showcases the life of tanners. Though the film was made on a shoestring budget, he screened it across Punjab villages on his own to raise social awareness.”

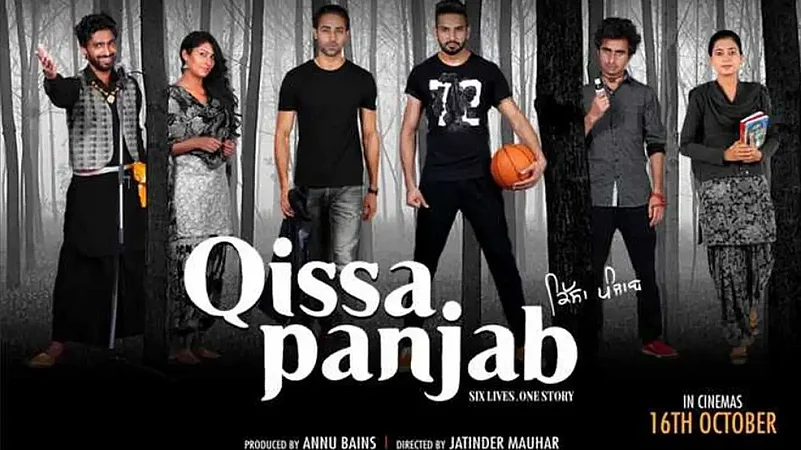

Ami specially mentions filmmaker Jatinder Mauhar. Prior to Udta Punjab (2016) that highlighted the drug abuse problem in Punjab, Mauhar had made Qissa Punjab (2015) on the same subject.

“Though there is no comparison between the successes of two movies, we always manage to recover the money that we invest in our movies,” says Ami, who has to his credit documentary films like Karze Haith (2001) on the plight of farm labourers.

Ami has co-authored Sadde Aale with Jatinder Mauhar, director of the film that released on April 29. The movie happens to be the last completed film of late actor Deep Sidhu who died in a car crash earlier in February. The movie depicts how farm distress has been weakening Punjab’s farming families.

Ami says Punjab society is afflicted with problems like drugs, violence, casteism and patriarchy and that filmmakers must feel socially responsible to address these issues.

“The art must challenge social evils instead of endorsing them. If your movies celebrate all these issues, you may make a lot of money, but you will be failing as an artist,” he says, before asking, “The question remains whether cinema being a commercial entity wants to humanise the society or not.”