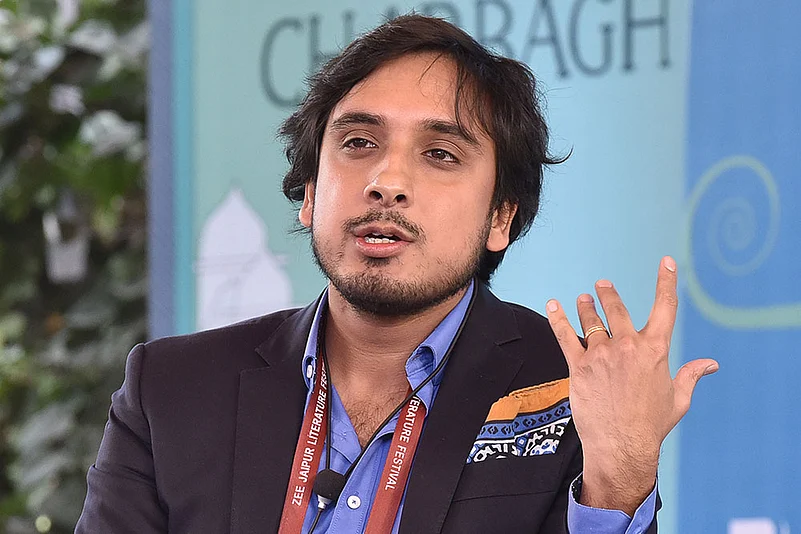

Charmed and dazzled by Kanishk Tharoor’s debut, Swimmer Among The Stars, a collection of bijou, lapidary short stories, critics have lain on their backs, legs akimbo, begging to have their tummies tickled. Alongside the breathless reviews have been the many breathless profiles focusing on his illustrious parentage (his father is Shashi Tharoor, and his mother Tilottama Mukherjee is a prominent academic) and his glamorously peripatetic upbringing.

It is, no doubt, hard on Tharoor fils, in India at least, to have his work seen through the prism of his father’s celebrity, to be always uncertain of whether praise is sincerely meant or criticism is motivated by envy. For those of the latter persuasion, there is fuel for their ire in opening sentence of the collection’s opening story, Elephant at Sea: “In the late summer of 1979,” it begins, “the second secretary of the Indian embassy to Morocco received a cable that undid his considerable years of training and left him floundering.” In the next paragraph, Tharoor writes: “With telegrams to the ministry, it was important, first, to be terse so that you were considered economical and second, to be sharp... WHY SHIP ELEPHANT STOP EMBASSY ALREADY HAS CARS STOP.”

Glib and jaunty, the reader might expect from this a trifling tale. Instead, Tharoor turns the story into something plangent, elegiac. It retains its humour but the mahout and elephant are linked by a loneliness, a sense of dislocation that marks all the stories. “You and I”, the mahout tells his charge, as he prepares to flee into Morocco’s space, its silence, “are now so alone in the world”. In another story, UN ambassadors, referred to by the countries they represent, find themselves marooned in space as the world disintegrates. Connection, though sought, in weightless games of table-tennis, in dancing, in sex, is almost impossible to achieve. In yet another story, a group of patrons in a tea house continue to talk and drink as clouds of dust are raised by the hooves of the horses of advancing conquerors.

The barbarians are at the gate and is there anything left to do but carry on as if the determined act of drinking tea can not only suspend reality but extinguish it? But the tea drinkers have as much to fear from their own compatriots, angered by their indolence and disrespect. Tharoor is drawn to those out of kilter with the world, those who are left behind or who opt out. In the title story, an old woman, the last living speaker of a language, tries to explain to a group of well-intentioned ethnographers what it feels like to lose your mother tongue but to still feel its rhythms, to see its ghosts, to have it ripple the smooth surface of the language of daily use.

How can people survive the severing of links to their history, the loss of objects that contain whole human stories? Some of the stories in Swimmer Among The Stars, particularly the 14-part Mirrors of Iskander, take the form of those shards of history found in museums that purport to tell us something of who we were and perhaps who we now are. A Lesson in Objects, the only story here told in the first person, appears incongruous at first, a banal rendering of the end of one juvenile affair and the strangled beginning of another, but it is of a part with the others in its protagonist’s very sense of being out of time and place, misunderstanding something crucial about the ways of the world.

That lack of understanding leads to pain as a poor miner discovers in Portrait with Coal Fire, when he sees a photograph of himself in a magazine sent to him by the photographer. He is confronted by an image of how he is seen by the world and he recoils, hoping desperately that the photographer will make amends and print a photograph of how he sees himself, a posed one with his family with him “wearing a clean lungi, [his] hair parted to the side...proud and smiling”. Swimmer Among The Stars is a promising debut, wide-ranging and thoughtful. It is in places a touch precious, too determinedly wistful—I found myself longing for some loss of narrative control, for the prose to break free of its decorous shackles—but this is mere quibble.

The Word

Some reviews of Kanishk’s book have also mentioned his twin brother—a commentator with Washington Post—and his recent wedding festivities.