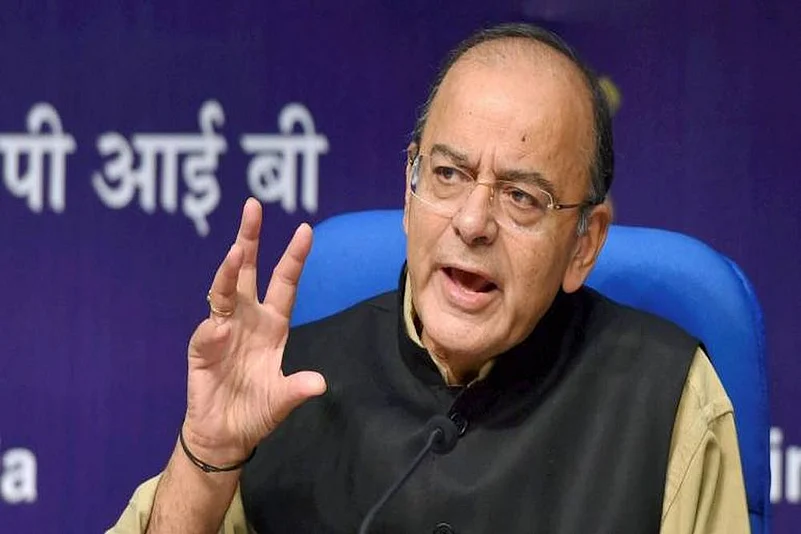

The country’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s “intolerance” to criticism from a Cabinet colleague triggered the opening Constitutional amendment that prohibited free speech if it “adversely impacts friendly relations with foreign states”—a law that paradoxically stemmed from an exhortation for a united India, Union minister Arun Jaitley said on Friday.

It was his resentment over industry minister Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s appeals for an “Akhand Bharat” amid the 1950 Delhi Pact which sought to guarantee minorities in nascent India and Pakistan their rights that led Pt Nehru to change of legislation which hindered “free speech” that is a part of the “basic structure of the Constitution”, Jaitley noted on social media, describing the incident as a “forgotten chapter” in India’s post-Independence history.

Advertisement

“If an amendment dilutes it (free speech) through an unreasonable restriction, it will be liable for challenge on the ground of violation of the basic structure (of the Constitution),” according to the Facebook post, made on the 117th birth anniversary of Mookerjee who went on to found the Bharatiya Jana Sangh which in 1980 became the BJP of which Jaitley, 65, is a senior leader.

The bilateral agreement, also called the Nehru-Liaquat Pact (Liaquat Ali Khan being Nehru’s Pakistani counterpart), on April 8, 1950, prompted Dr Mookerjee, a representative of the Hindu Mahasabha he led for three years from 1943, to resign from the Cabinet in protest. The Calcutta-born leader took further strengthened his public position against pact by speaking “extensively” against it in Parliament and outside, reiterating that it went against his philosophy of ‘Akhand Bharat’ that meant Undivided India, Jaitley recalled.

Advertisement

“Pt Nehru over-reacted to Dr Mookerjee’s criticism”, as the ‘Akhand Bharat’ was, for the PM, “an invitation to conflict since the country could not be reunited other than by war.” Nehru advised his deputy, Vallabhbai Patel, to consider action against Dr Mookerjee. “After consultation with Constitutional experts, Sardar Patel’s opinion was that he could not prevent Dr Mookerjee from propagating his idea of ‘Akhand Bharat’ under the Constitution” and that it would require a Constitutional amendment if the PM wanted an end to the matter.

“Dr Mookerjee, on the contrary, claimed that Pakistan wanted a war and was already at war with us, having captured a part of our legitimate territory of Jammu and Kashmir,” says Jaitley. Thus, “to suggest that his speeches on ‘Akhand Bharat’ would lead to a war was not acceptable.”

Thus, in 1951, an amendment Bill on this was introduced in Parliament, which as a central assembly was duplicating earlier as a Constituent Assembly, notes Jaitley, who holds the finance portfolio in the present Narendra Modi ministry. The Facebook post, hailing Dr Mookerjee as an eminent parliamentarian and statesman, notes that he formed the Jana Sangh “as an alternative ideological pole” in 1950 when Pt Nehru’s Congress was the country’s dominant political party. “Today, the BJP has replaced the Congress as the key ideological pole in Indian politics.”

As for the pertinent Constitutional amendment, its circumstances have been discussed in detail in a book brought out last year, Jaitley pointed out. Republic of Rhetoric — Free Speech and the Constitution of India, by lawyer Abhinav Chandrachud, “traces the history of the entire debate on free speech from the Constituent Assembly till the publication of the book”.

Advertisement

The amendment Bill, Jaitley noted, was referred to the Select Committee of Parliament, of which the PM “himself became a member”. Its report, submitted within a week along with a note of dissent, was debated in the Lok Sabha on May 29, 1951. The Bill was eventually passed and became a part of the Indian Constitution despite opposition from “several senior members such as H.V. Kamath, Acharya Kripalani and Naziruddin Ahmad” besides Dr Mookerjee.

“They argued that such a provision does not exist in any Constitution in the world. It was too widely worded and could even prevent a legitimate debate of foreign policy issues. It was argued that the Constitution had been in force for only sixteen months and it may not be prudent to bring a hurried Constitution amendment,” says Jaitley. “But Pt Nehru was determined to go ahead. His principal response was if you criticise a head of a State or a foreign State, that country may launch a war against us. This would adversely impact India’s sovereignty.”

Advertisement

According to Jaitley, Pt Nehru argued that “we cannot imperil the sovereignty of the whole nation in the name of some fancied freedom which puts an end to all freedoms”. Dr Mookerjee countered that “such a widely-worded amendment could prevent a legitimate debate on issues pending with Pakistan, not merely on the treatment of minorities or what was happening in Jammu and Kashmir; it would also prevent us from commenting on issues relating to evacuee property.”

Jaitley’s post ridicules the very idea of the amendment, noting that the “world is consistently changing” and so are the international alignments. “Erstwhile opponents become allies or vice versa…. Governments can be cautioned or appreciated for the course they follow. They can even be criticised,” he added. “In the absence of debate and even criticism, there would be only one opinion expressed which is detrimental to a democracy.”