We are at the dawn of the golden jubilee year of India’s spectacular victory against Pakistan in an all-out war, fought on two fronts, bringing an end to the atrocities and carnage perpetrated by Pakistan on a peace-loving people in erstwhile East Pakistan. It is time to remember and reflect upon the sacrifices, complexity of stakes and decisions that altered the course of the Indian sub-continent’s history, besides redrawing its geography. Significantly, India catapulted itself as a power to be reckoned with in the world order. On December 16-17, 1971, over 92,000 West Pakistani soldiers, sailors, airmen, paramilitary personnel, policemen and civilians surrendered to India in East Pakistan, ending 24 years of Pakistani rule. Bangladesh was finally liberated!

Advertisement

The sacrifices were immense: 12,189 personnel of India’s armed forces were either killed, reported missing or wounded with lifelong disabilities.

ALSO READ: How The West Was Won

The estimate of Bangladeshi people killed ranges from three lakhs to three million. The death toll of Bangladeshis rose steeply in the months preceding the war, due to the genocide committed by Pakistani Army, aided by pro-Pakistani militias. This planned military crackdown, codenamed Operation Searchlight, was directed by Pakistan President Yahya Khan to crush the Bengali nationalist movement, with the ‘H hour’ set at 0100 hours on March 26, 1971. Almost concomitantly, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared independence.

Advertisement

Another disastrous fallout of Pakistan Army’s massacre was the massive influx of refugees from East Pakistan to India—the number touched 10 million in just four months. By June 3, 1971, the 509 refugee camps set up along the border were finding it impossible to cope with the scale of migration. Large camps, run by ex-army personnel, had to be established in eight states across India.

ALSO READ: To The East We Went and Won It For Them

For India the perils were clear. Besides the humanitarian crisis, the political, social, economic and security consequences could be disastrous. Described as a ‘holocaust unmatched since Hitler’, Pakistan’s objective of the genocide was to force Bengalis to seek refuge in India so that a demographic change could be effected, by replacing them with West Pakistanis. Exploiting the situation, Pakistani agents were infiltrated along with refugees for sabotage in India. Many were apprehended in Assam and Meghalaya.

Indian domestic opinion was growing strongly in favour of strong action and recognising Bangladesh. State legislative assemblies of UP, Bihar, Assam, Nagaland and Tripura passed resolutions recognising the state of Bangladesh. The Centre was initially cautious, clarifying in July 1971, “we are not opposed to the recognition”, and the decision would be taken at an appropriate time, “when we find that it is in our national interest and also of the freedom fighters”.

ALSO READ: Bayonets Fixed: Fight Of Their Lives

The timing of India’s recognition of Bangladesh was a critical decision. On the one hand, for the recognition to be effective, ability to intervene decisively in East Pakistan was an imperative. This would involve preparations for a swift military victory, before Pakistan could secure UN intervention, with active American and Chinese assistance. On the other hand, there was a limit to how long the liberation struggle could survive in the face of Pakistani barbarism.

Advertisement

The potential of Chinese Communist influence was around in the wings—the Naxalbari revolt in West Bengal, insurgencies in Northeast India. If India did not rise to the hopes of a secular Awami League, they may well be forced to seek alternatives for survival, or perhaps be compelled to cede space to ‘extremists’, seeking to succeed on an India ‘let us down’ plank.

The political leadership of East Pakistan, including the Awami League, had for long tried to get their due within the larger construct of united Pakistan. The seeds of the political struggle were sown as early as 1948, when Jinnah refused to accept the demand for Bengali to be recognised as a national language. There were riots in the 1950s over the Pakistan government’s decision to accord national language status only to Urdu. The fundamental causes of language and ethnic marginalisation, were catalysed by inequitable distribution of national resource, economic exploitation and unfair political representation in the Pakistani parliament.

Advertisement

ALSO READ: All Boots Lead To The Sugar Bowl

The government of Pakistan’s negligent handling of the November 1970 Bhola cyclone that killed 5,00,000 people was the proverbial last straw. Riding on the wave of resentment against West Pakistan, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League won a landslide victory in the December 1970 general elections, securing 160 of the 162 seats in East Pakistan. His arch rival, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party, won 81 of the 138 seats in West Pakistan. But neither the military dictatorship nor the political leadership (read Bhutto) in the West was prepared to share power with East Pakistan.

Advertisement

Between December 1970 and March 1971, Mujibur Rahman’s hopes for the constitutional acceptance of his ‘six-point demand’ were finally dashed. The ‘six points’ were aimed at removing the inequality between the two wings of Pakistan. They called for a true federation of Pakistan: the federal government dealing only with defence and foreign affairs; measures to stop the flight of capital from East to West Pakistan; powers of taxation and revenue collection to be vested with the federating units; separate accounts for the foreign exchange earnings of the two wings; freedom with the federating units to establish trade links with foreign countries; foreign exchange requirements of the federal government to be shared proportionately and East Pakistan to have a separate militia or paramilitary force. The March 1971 Op. Searchlight, targeting students, the intelligentsia and Awami League, sealed the fate of the ‘six points’ finally, and quashed the nascent nation’s talent.

Advertisement

Work on contingency plans for Pakistan’s military crackdown against East Pakistan had commenced soon after the 1970 December election results were known. By end February, the surge in military deployment in East Pakistan had begun, and so were the diplomatic preparations. Yahya Khan was assured of America’s commitment to Pakistan’s integrity.

By 1969, Pakistan was proving itself to be more useful than ever before to the US, by providing secret channels of communication with China. The top US leadership—Nixon and Kissinger—were of the view that the seething China-Soviet Union tension could be exploited to benefit the US. Given China’s size and growing importance, the US could leverage its relations with China to counterbalance Soviet involvement in the Third World, which would help in a respectable exit from Vietnam.

Advertisement

The US tilt towards Pakistan had two immediate effects; first, President Nixon ordered a review of the earlier Johnson administration’s embargo on US arms supply to Pakistan; and second, US presidential directions not to ‘squeeze Yahya Khan’ in this crisis, i.e. the US would look the other way even as the deplorable genocide was perpetrated by Pakistan. Meanwhile, facilitated by Pakistan, Kissinger visited China in July 1971. Following the visit, it was made clear to India that the United States would not intervene in the event of conflict between India and Pakistan, even if China did so.

ALSO READ: 50 Years Of Unlearning

Advertisement

China, on its part, adopted a cautious stance, driven by multiple considerations. First, the splitting of Pakistan was not in China’s interests, as a liberated East Pakistan would naturally tilt towards India. Second, China needed to retain its influence on the pro-China political parties. These parties had not performed well in the December elections, and with the Pakistani Army’s onslaught against the Bengalis, the remaining influence would further weaken. For these two reasons, China was not inclined towards favouring Pakistan’s military solution.

At the same time, China needed to support Pakistan, as their relations were growing closer after the India-China war of 1962. In 1963, Pakistan had illegally ceded 5,180 square kilometres of strategic territory in Ladakh’s Shaksgam valley to China. After the Johnson administration’s embargo on supply of arms, Pakistan was becoming dependent on China for military and economic aid, while trying to open up relations with the Soviet Union.

Advertisement

ALSO READ: Taka Talks In A Tailored Suit

In early 1969, in the China-USSR military clash along the Ussuri River, China had suffered relatively heavier losses. In Vietnam, China’s involvement in supporting Ho Chi Minh against the US was increasing. Opening two fronts, against two superpowers, weighed heavily on China’s strategic calculations. Under these circumstances, Pakistan’s efforts in bringing about a China-US rapprochement were too significant to be disregarded.

Overall, China chose to be indifferent to the massacre in East Pakistan, calling it an internal problem of Pakistan, even as it continued to supply arms and ammunition to Pakistan. China was bitterly critical of India’s actions, like harbouring Bangladesh’s government in exile, accusing India of expansionism. The massive influx of refugees was of little concern to China.

Advertisement

ALSO READ: Going Mega For Growth

India had open borders with Nepal, Sikkim, and Bhutan. Sikkim was not part of India then, and there were road links between Nepal and China, which could work to India’s disadvantage should China choose to intervene. China and East Pakistan together threatened the Siliguri Corridor, which connected India with the Northeast, where both China and Pakistan were fanning insurgencies. Amidst all this there were occasional attempts by China to mislead India by showing signs of attempting a thaw in relations.

With the China-USSR rift intensifying, Moscow was keen to deepen its relations with India. In 1969, Soviet Union proposed a Treaty of Friendship to secure a special relationship with India. India was initially reluctant due to its commitment to the policy of non-alignment. For the crisis in East Pakistan, on the one hand, Moscow wanted to dissuade India from military intervention, and on the other hand, tried to persuade Pakistan towards a political resolution. But with the growing connect between US and China, and their support for Pakistan, the die was cast for an exclusive relationship between Moscow and India.

Advertisement

On August 9, 1971, the foreign ministers of India and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics signed the treaty of ‘Peace, Friendship and Cooperation’. The treaty, valid for twenty years, was aimed at “expanding and consolidating the existing relationship of sincere friendship” between the two countries. Article IX of the treaty stated, “In the event of either party being subjected to an attack or a threat thereof, the high contracting parties shall immediately enter into mutual consultations in order to remove the threat and to take appropriate effective measures to ensure peace and the security of their countries.”

Meanwhile, Pakistan, emboldened by the support from US and China, and the ambiguous position taken by many countries, with or without a nudge from the US, hardened its stance. In August 1971, Pakistan first issued a white paper, squarely blaming Mujibur Rahman and the Awami League for the crisis. Mujib was tried for treason, 79 of the 160 elected members of the National Assembly, and 195 of the 228 members of the Provincial Assembly, were disqualified.

Advertisement

Beginning September 1971, a civilian governor and ten provincial ministers were appointed. Two of the ten ministers were rebel Awami League leaders, the other eight were unelected. Having marginalised the Awami League, the Pakistan government ordered by-elections for the vacant seats, to be held from November 25 to December 9, 1971. This was meant to be Pakistan’s political solution to the crisis.

In August 1971, Pakistan also issued a district-wise list of refugees, which included approximately one-fourth of the actual number of people that fled from East Pakistan as a result of the genocide. According to analysts, the list just about covered Muslim refugees, implying that Hindu refugees would not be allowed to go back. The situation was a clear message to India. There would be no political solution.

Advertisement

India decided to build military pressure. Support to Bangladeshi freedom fighters was increased. The force was organised into action groups, intelligence cells and guerrilla bases. Between August and November 1971, three field batteries of artillery were raised, comprising deserters from the Pakistan Army. In November, the East Bengal regular battalions were grouped into three brigades. A 500-strong Mukti Bahini naval force and Mukti Bahini air force also came into being. By end of November 1971, Mukti Bahini comprised over 83,000 men, of which 51,000 operated inside East Pakistan.

Deeply concerned at America’s carte blanche to Pakistan and the attempts to sow dissent between Awami League leaders and freedom fighters, India stepped up its diplomatic blitz. The USSR was inclined to maintain a balanced posture, using the August 1971 Treaty of Friendship with India, at best, as a tool to coerce Pakistan for a political resolution of the crisis.

Advertisement

The Indian leadership reached out to London, Brussels, Vienna, Washington, Paris, Moscow, Bonn and others. On November 4, 1971, then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi took a tough stance at her meeting with Nixon. The following day came the unfortunate remark by Nixon, that she was being “a bitch”. Despite the mixed reactions in Europe, India was clear that there was no place for international mediation between India and Pakistan, and that scaling down troop deployments from the borders was unacceptable. In India’s view, the solution lay with Pakistan releasing Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, and resuming negotiations with Awami League.

On the ground, Mukti Bahini operations and border intrusions increased in frequency and intensity. Pakistan made frantic efforts to seek UN intervention, and concomitantly put up a façade of a civilian government. Besides the deceit of a sham civilian government in East Pakistan, Yahya Khan was also grappling with internal faultlines in West Pakistan, between his own ambitions of holding on to power, and those of Bhutto’s. By now, Pakistan had assessed that with the Soviet Union solidly behind India, UN intervention was unlikely to succeed.

Advertisement

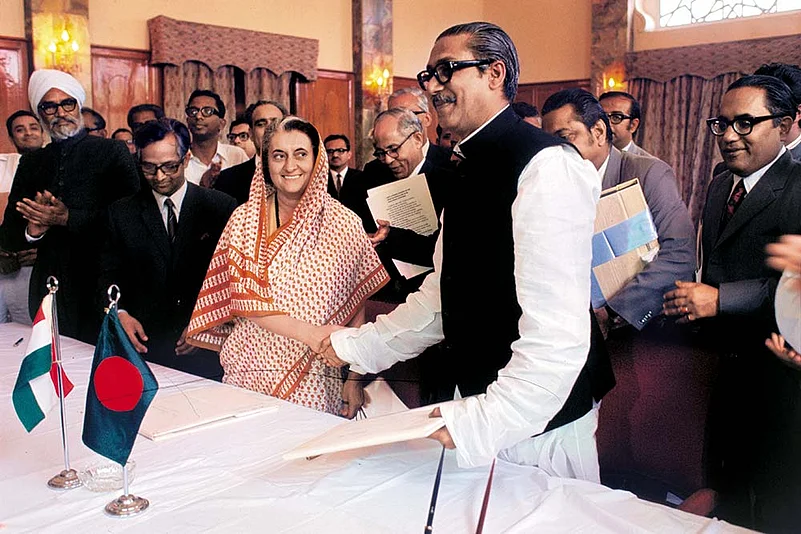

On December 3, 1971, Pakistan launched preemptive air strikes on many Indian air bases along the western front. Pakistan’s strategy was to attack in the West, so as to relieve pressure in the East. This was more than enough reason for India to take the much awaited decision of recognising Bangladesh. The 1971 India-Pakistan war for liberation of Bangladesh had begun!

The time available to India was limited, as the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet sailed into the Bay of Bengal through the Malacca Strait. The Seventh Fleet, led by the 75,000 tonne nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, had over 70 fighters and bombers. The fleet included the guided missile cruiser USS King, guided missile destroyers USS Decatur, Parsons and Tartar Sam, and a large amphibious assault ship, USS Tripoli.

Advertisement

Despite the pressure, the war witnessed some very fine operational manoeuvres by India’s armed forces, executed in a superbly shaped diplomatic and political environment, where the entire nation stood as one. With total air dominance provided by the IAF over East Pakistan and a de facto naval blockade, the Indian Army, supported by the BSF and the Mukti Bahini as the force multiplier, executed a ‘lightning campaign’, and Dhaka fell in less than 13 days, providing the finest military victory for India. More importantly, a victory for the people of Bangladesh against an unjust, oppressive and fanatical regime.

(The author is member of the National Security Advisory Board; director, School of Military Studies, Strategy and Logistics, Rashtriya Raksha University and Former Deputy Chief of Army Staff. Views expressed are personal.)