As I was reading Vidhu Vincent’s drawings and the lines that accompanied them on the Emergency, I wondered, a bit ruefully, how Narendra Modi failed in ensuring that trains in India ran on time! If he willed Indian Railways into punctuality in May 2014, that would have given a magnificent ‘Sab ka saath sab ka vikas’ resonance to it. I suspect the reason for this apparent failure lies elsewhere. Being a man of futuristic vision, he thought it would be better to focus his attention on smart cities and bullet trains instead of wasting precious time on India’s unmodern, noisy, inelegant trains. The numerous smart cities across the country that materialised from nowhere in the past seven years, and the hundreds of brand-new bullet trains that crisscross our vast republic at breakneck speed, testify to this assumption made in good faith.

Advertisement

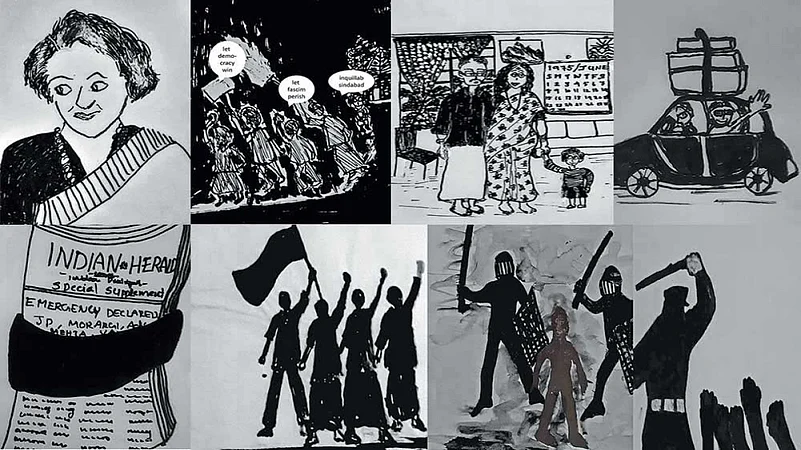

Vidhu’s graphic memoir on the Emergency is a personal tale and a critique. She is, literally, a child of the Emergency. Like ‘midnight’s children’, one is tempted to call people born during the 21 dark months of the 1970s ‘Emergency’s children’, but the trouble is they are now living through a hell much worse than the one they were born into. Although the period between 1977 and 2014 cannot be described as heavenly by any stretch of imagination or intellection, one realises, rather poignantly, that even heaven and hell are perceived in relative terms.

If rule of law can be used as a yardstick without any regard to issues of ethics and morality, the Emergency was perfectly legal with some aberrations. The undeclared Emergency during the past seven years has been mostly illegal. A comparative look at the mental state of the victims (mostly Muslims) of Sanjay Gandhi’s forcible sterilisation campaign and the cow vigilantism of today can possibly clinch the truth of the relative nature of heaven and hell on earth. A Muslim man who might have gone through both ordeals must feel thankful to Sanjay for limiting his murderous zeal only to children not yet born!

Advertisement

Vidhu’s memoir is a subtle critique of how Kerala, including her own family, vociferously supported the Emergency. The state, which always stood out for its progressive veneer, shamelessly voted back to power a government that brutally implemented the Emergency. Kerala has acted in total contradistinction to the national mood on many occasions, but the two that bear distinctive political implications are the state’s ignominious celebration of the Emergency and its contemporary rejection of Hindutva.

The former shows the state up as one with no compunction in embracing authoritarian tendencies. The latter, interestingly, reflects an uncompromising stance against communalism and bigotry. Is it then fair to conclude that the Malayalis are comfortable with authoritarianism so long as it is secular and consistent with some semblance of constitutionalism? Or is it that they have evolved over the years to become a bulwark against both communalism and authoritarianism? A third possible inference would be that the state’s rejection of majoritarianism is merely a result of its demographics in which the minorities constitute nearly half the population, and a large chunk of the majority community is still in thrall with Kerala’s largest Hindu party (in the limited sense of having a substantial number of Hindus as members and supporters)—the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

Vidhu Vincent’s graphic memoir is not an attempt at solving these vexatious and intriguing riddles about Kerala, but the drawings and the text point to all of these without being rhetorical. It also portrays the conscientious rebels who acted out of their political convictions even when their families and communities remained ardent admirers of Indira Gandhi and her Emergency. That she was born into a diehard Congress and devout Christian family but evolved into a secular leftwing political activist and filmmaker is also a reflection of not only her own metamorphosis, but of many others in that generation whose time of birth coincided with the decline of the values and ideals that defined the freedom movement and the founding fathers (and mothers) of the Republic.