In southern Chhattisgarh and its bordering areas in Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, guerilla platoons are being wiped out in security offensives.

1928, Mao Zedong, a central committee member of the Communist Party of China (CPC), presented the idea of an agrarian, ‘protracted people’s war’ for the Chinese revolution.

The first fruits of the Mao-inspired land, crop and wage-related agrarian armed struggle came in the revolts in Telangana (1946-51) in south India and Bengal in eastern India (1946-51).

Tracing The Naxalites: How India’s Maoist Insurgency Is Crumbling in 2025

The Maoist doctrine of agrarian armed struggle influenced sections of India’s Left since the 1940s and posed a major security threat to the State, only to crumble rather rapidly in 2025

Muppala Lakshmana Rao must be quite a restless man now. 2025 has been the worst year for India’s Maoist rebels, who launched a mission to overthrow the Indian State through an armed, agrarian revolution way back in 1967. Known to the world as Ganapathi, Rao is one of the architects of the revival of Left-wing insurgency in India, after the first wave of the Maoist aka Naxalite movement faltered in the early 1970s. Over time, the Indian Maoists became one of the largest and most lethal Left-wing armed groups in the world, perhaps second only to the western Asia’s Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

He is past his mid-70s. Going by his organisation’s practice for elderly leaders, he likely lives in some urban centre—away from the jungle life of guerrillas. His party, the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist), is faced with unprecedented setbacks in its stronghold of central India’s forested and hilly tracts. Reports of rapid crumbling of the mighty force that he helped build over four decades keep pouring in.

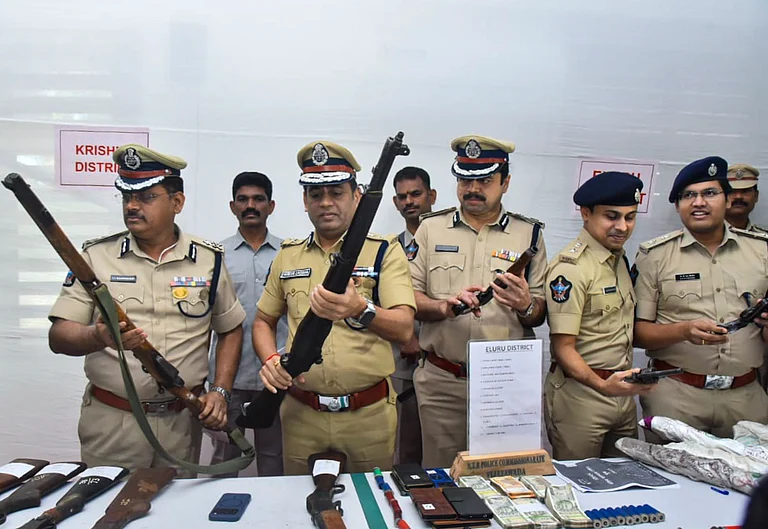

In southern Chhattisgarh and its bordering areas in Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, guerilla platoons are being wiped out in security offensives. Dozens of fighters are laying down their arms. The Maharashtra-Madhya Pradesh-Chhattisgarh (MMC) zonal committee has publicly sought three months’ time to surrender. The Telangana state committee has unconditionally extended its unilateral ceasefire.

“This is the first time since the Naxalbari (1967) and the Srikakulam (1968) struggles that four members of the central committee and 17 members of state committees, in addition to the general secretary, have been martyred in the space of a year,” the party said in a statement issued in September 2025 on the occasion of the 21st anniversary of the CPI-Maoist’s formation. It acknowledged the need to address “questions arising in the revolutionary camp regarding its future”.

The worst was yet to come. In just about two months after the statement was issued, five more central committee members were killed—Odisha in-charge Modem Balakrishna, key Jharkhand leader Sahdev Soren and Kadri Satyanarayana Reddy, Katta Ramachandra Reddy and Madvi Hidma of the core Dandakaranya leadership, as well as several state committee members. Besides, four central committee members, Pothula Padmavathi (Sujatha), Takkalapalli Vasudeva Rao (Ashanna), Pulluri Prasad Rao (Chandranna) and Ramdher (Majji Dev) surrendered before the police.

Above all, politburo member Mallojula Venugopal Rao (Sonu), Ganapathi’s comrade for nearly five decades and one of the architects of the Maoist structure in its heartland of Dandakaranya, has not only surrendered before the police along with five dozen fighters with their weapons, but also called the armed struggle a failed venture and called upon others to lay down arms. The surrenders organised and encouraged by Sonu and Ashanna led to the handing over of 227 weapons to the state forces.

As one of the last active organisers of India’s Maoist movement revival, Ganapathi needs to get in touch with the remaining politburo members, Devuji and Misir Besra (Sunirmal), and central committee members Malla Raji Reddy (Satyanna) and Ganesh Uikey (Paka Hanumanthu) of the central regional bureau and Asim Mandal (Akash) and Patiram Majhi (Anal-da) of the eastern regional bureau. Without intervention from a top leader with wide acceptance among the cadres, preventing the splintering or liquidation of different state units might be just a matter of time.

However, being one who has a bounty of Rs 2.5 crore on his head, Ganapathi, India’s ‘most wanted’ anti-State actor, has many traps laid out for him. General secretary Nambala Keshava Rao alias Basavraju was killed in May along with 27 other members of a platoon because some members of his unit had leaked information to the cops. In September, Satyanarayana Reddy and Ramachandra Reddy were picked up from their urban centres because cadres who had been their couriers had surrendered. Hidma was killed in November because the same people who arranged for his movement out of Bastar to Andhra Pradesh for medical treatment had tipped the police of his whereabouts, the Maoists alleged.

Who remains committed and who has turned a traitor is a difficult question, more so for Ganapathi, for whom the security agencies have now deployed additional resources.

1928, Mao Zedong, a central committee member of the Communist Party of China (CPC), presented the idea of an agrarian, ‘protracted people’s war’ for the Chinese revolution—as opposed to the Russian communist line of urban armed insurrections by the working class. This idea was then rejected by the CPC’s top leadership, but accepted in 1935. This started influencing a section of leaders and organisers of the Communist Party of India (CPI) in the 1940s, as the Chinese national liberation movement made fast progress with Communists in a key role.

The first fruits of the Mao-inspired land, crop and wage-related agrarian armed struggle came in the revolts in Telangana (1946-51) in south India and Bengal in eastern India (1946-51). The CPI’s guerrilla squads snatched weapons from the police and managed to ‘seize and distribute’ thousands of acres of land and tonnes of crops among the landless and poor. At the same time, hundreds of farmers died fighting the private armies of the landlords and the security forces.

While the party leadership rejected such armed struggle afterwards, and opted for the new Soviet line of ‘peaceful transition to socialism’, the ‘Great Debate’ between the Communist Party of Soviet Union (CPSU) and the CPC sharply divided the CPI. The CPC’s June 14, 1963, letter to the CPSU calling for ‘resolute revolutionary struggle by the people of all countries’ emboldened the pro-Chinese elements in the CPI.

Following the CPI’s 1964 split, the pro-Chinese organisers went with the newborn CPI(Marxist). They moved out of the new party in 1967 after West Bengal’s new state government, which included CPI(M) politburo member Jyoti Basu as the home minister, ordered the police to open fire on agitating farmers in northern West Bengal’s Naxalbari, where the CPI(M)’s farmers’ wing had called for armed actions for the ‘seizure’ of land and crops from the landlords.

The armed movement in Naxalbari itself died down within a few months, but Naxalbari-style armed programmes had spread to southern Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and Andhra Pradesh by the end of the year. Two separate parties were launched in 1969—the Charu Majumdar-led CPI(Marxist-Leninist) or the CPI(ML), which had an all-India presence, in April; and the Kanai Chatterjee-led Bengal-based Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) in October.

After creating waves of agrarian armed struggle in different states, the movement quickly faltered by 1971-72. Most members of the central committee and state committees were either killed, jailed or had quit/split by mid-1972. It was during this immediate post-1972 period—when the Naxalite movement had nearly exhausted its resources and energy—that the likes of Ganapathi, Sonu, Basavraj, Devji, Katakam Sudarshan alias Anand and Cherukuri Rajkumar alias Azad, among many others, came to the Maoist stream through the Radical Students’ Union (RSU), founded in 1974, with Sonu’s elder brother and Sujatha’s husband, Mallojula Koteswara Rao alias Kishanji, as a key figure.

When the CPI(ML) (People’s War) was formed in 1980, Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, a member of the CPI(ML)’s original Andhra state committee, became its general secretary and Kishanji was Andhra state unit secretary. Ganapathi headed the Karimnagar district committee.

Re-organisation was also taking shape in Bihar. During the 1980s, CPI(ML)(Liberation) and CPI(ML)(Party Unity), both of which had first generation Naxalites, had gained strength in central Bihar. The MCC, which had shifted its base to south Bihar (now Jharkhand) after early setbacks in Bengal, had consolidated its influence by the mid-80s.

The Maoists’ lethality has reduced—16,463 violent incidents were recorded between 2004 and 2014, but this number came down to 7,744 during 2014-24.

The movement impacted mainstream politics and rural life in many ways. Apart from bringing to the public sphere the nature of land, crop and resources-based exploitation in rural India, many of their demands entered the mainstream, though in diluted forms. But their mission was not merely extracting demands—they wanted to capture State power.

In 1980, soon after the formation of the People’s War, the party sent a group of about three dozen cadres split into seven squads to Andhra—bordering, densely forested and more inhospitable terrains of Dandakaranya to build a base area for the ‘standing army’ that the party wanted to set up. Subsequently, as the Andhra movement started facing setbacks with gradually increasing state offensives, a greater number of People’s War leaders and cadres shifted to Bastar in the 1980s.

The People’s War guerrillas mobilised the local tribal population, chiefly the Gonds and the Koyas, to stop paying a variety of taxes to the forest department and occupy forest land for cultivation. They ‘seized’ some land illegally occupied by the local influential people and distributed them among the landless. They built ‘paddy banks’ and ‘seed banks’ to make the area self-sustainable through improved and increased farming. They ‘confiscated’ oxen, goats and sheep from the landlords and moneylenders, distributed them among the poor farmers, and dug pits to store the dung as ‘manure banks’.

The likes of Ganapathi, Kishanji, Sonu, Basavraj, Ravulu Srinivas (Ramanna), and Satyanna, among others, underwent training from some former Liberation Tigers of the Tamil Eelam (LTTE) commanders in ambush tactics and the handling of gelatine, twice—in 1987 and 1989. In 1992, following internal strife in the People’s War, the party expelled Seetharamaiah and elected Ganapathi as the general secretary.

From the mid-1990s, they started forming Janathana Sarkars or people’s governments to administer areas under their armed teams’ control in Dandakaranya. Squads (5-7 members) were merged to form platoons (25-30 members) and platoons were merged to form companies (60-80 fighters). In 1998, the People’s War merged with the Party Unity (PU) and on December 2, 2000, the unified People’s War launched the People’s Liberation Guerilla Army (PLGA). In 2004, the MCC merged with the People’s War to form the CPI-Maoist. The party’s top leadership had the likes of Sushil Roy, Prashanta Bose and Narayan Sanyal who had joined the movement during its first wave in the late 1960s. The very next year, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh identified it as India’s single largest internal security threat.

The CPI-Maoist carried out some daring strikes on the security forces soon after but, according to the party’s statements, “the revolutionary movement across the country reached a defensive position by 2012”. The Bengal movement collapsed after Kishanji’s death in November 2011. Movements suffered in Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha as well. Their repeated attempts to create a base at the trijunction of Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu failed to bear any fruit. This prompted the party to shelve its plan to “develop the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA) into a regular army”.

How the Maoists’ lethality reduced becomes evident from the following facts—16,463 violent incidents involving the CPI-Maoist were recorded between 2004 and 2014, but this number came down to 7,744 during 2014-24. Whereas 1,519 security personnel were killed by Maoists during 2004-14, the fatalities came down to 509 between 2014 and 2024. Maoist violence claimed the lives of 1,005 civilians and security personnel in 2010, but this death toll came down to 150 in 2024.

On the other hand, the losses on the Maoists’ side kept increasing, as the State multiplied specialised force deployment and their firepower, used modern technologies for aerial surveillance and defusing improvised explosive devices, deployed choppers to airlift injured soldiers and drop supplies, besides deepening their ground intelligence network.

By the beginning of 2025, the security forces had set their entire focus on eight districts. The quadra-junction of Sukma (Chhattisgarh), Malkangiri (Odisha), Alluri Sitarama Raju (ASR) of Andhra Pradesh and Bhadradri-Kothagudem in Telangana was one key focus, another being the Abujmarh belt comprising Chhattisgarh’s Narayanpur and Kanker districts and their neighbouring Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra. The third major focus was the Indravati Tiger Reserve in Bijapur district, bordering Gadchiroli.

“The Party and the PLGA forces suffered severe losses because we did not withdraw some troops from Dandakaranya, the main centre of the Kagar war, to other regions,” the party’s central military commission said in a statement dated December 1, instructing the party forces to decentralise, move in small formations and avoid concentrating in smaller areas.

The occasion was the silver jubilee of the PLGA’s foundation. However, there wasn’t much scope for any celebration, not at least in December 2025. They are on the run, prioritising the protection of the remaining leadership over displaying any might.

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya is a journalist, author and researcher

This article appeared as The Red Army in Outlook’s December 21, 2025, issue as 'What's Left of the Left' which explores the challenging crossroads the Left finds itself at and how they need to adapt. And perhaps it will do so.