The Rs 80,000-crore Great Nicobar project is criticised for endangering one of the world’s most pristine ecosystems and violating tribal and environmental safeguards.

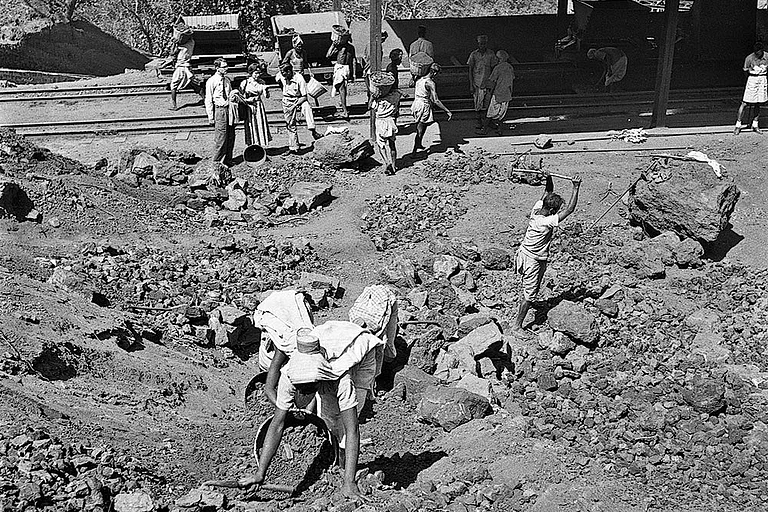

Massive deforestation, displacement of indigenous communities, and disregard for seismic risks highlight the project’s ecological and moral costs.

The project reflects a failure of governance and scientific reason, prioritising spectacle and profit over sustainability.

The Great Nicobar Catastrophe

The Great Nicobar project is not merely environmentally destructive; it represents a collapse of governance, scientific rationality, and moral responsibility.

In the name of Viksit Bharat (Developed India), the Indian state is preparing to commit an act of environmental and cultural genocide on one of the planet’s most pristine ecosystems. The Rs 80,000-crore Great Nicobar Island mega-project—comprising an international container trans-shipment terminal, an international airport, a power plant, and a township for over 3.5 lakh people—epitomises the hubristic development model that equates construction with progress and spectacle with success.

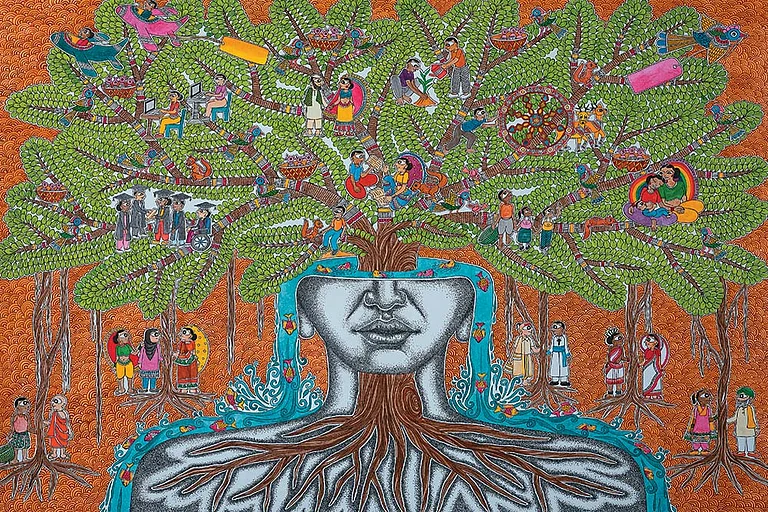

Great Nicobar, the southernmost island of the Andaman–Nicobar archipelago, shelters ancient rainforests, critically endangered species, and two small indigenous communities—the Shompen and the Nicobarese—whose ways of life are woven into the island’s ecology. Situated on an active seismic fault line and still bearing the scars of the 2004 tsunami, it is among the worst possible sites for heavy infrastructure. Yet, the government, in its characteristic haste, has bulldozed through environmental clearances, ignored tribal rights, and dismissed scientific warnings as anti-national obstructionism.

The Great Nicobar project is not merely environmentally destructive; it represents a collapse of governance, scientific rationality, and moral responsibility. The long-term ecological, cultural, and economic losses will dwarf any strategic or commercial gain. Above all, it reveals a political culture that values spectacle over sustainability and domination over deliberation.

Ambition Without Wisdom

The project’s scale is staggering. About 166 square kilometres of dense tropical forest will be converted into integrated development zone housing: A deep-water transshipment port at Galathea Bay to rival Singapore and Colombo; a greenfield international airport designed for civilian and potential military use; a 450-MW power plant; and a new township for over 350,000 people—nearly 200 times the island’s current population of 1,761, mostly indigenous.

The government’s justification rests on strategic grounds: Great Nicobar’s location near the Malacca Strait supposedly makes it vital to India’s Indo-Pacific ambitions. The port, it argues, will reduce dependence on foreign hubs; the airport will enhance both connectivity and military readiness. Employment generation and “regional development” are the familiar refrains.

But beneath the rhetoric lies deep irrationality. Great Nicobar’s remoteness, fragile ecology, and seismic instability make it one of the least suitable sites for such development. India already possesses substantial under-utilised port capacity along its coastline, which could be upgraded at a fraction of the cost and risk. According to government data, the 12 major ports of India had a combined handling capacity of roughly 1,630 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) in FY 2023-24, while actual throughput was about 855 million tonnes, implying 52 per cent capacity utilisation. Further, the broader Indian port sector shows current capacity of about 2,604 MTPA and projected annual additions of 500-550 MTPA up to FY2028.

In contrast, regional competitors dominate container shipping: the Port of Singapore, for example, handles more than 40 million TEUs (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units) annually, while the Port of Colombo achieved a record 7.78 million TEUs in 2024. Given these numbers, embarking on a mega-transshipment hub in a remote seismically-vulnerable island like Great Nicobar appears speculative at best. India already possesses underutilised port capacity along its coastline, which could be upgraded at a fraction of the cost and risk. Competing with Singapore’s decades-old maritime networks and Colombo’s strategic geography is a fantasy.

No comprehensive cost-benefit or disaster-risk assessment has been published. The project appears driven more by the regime’s obsession with headline-grabbing announcements than by economic or strategic logic.

The Environmental Catastrophe

The environmental cost is incalculable. The first phase alone involves clearing about 50 square miles of undisturbed rainforest—between 850,000 and 5.8 million (some estimates indicate ten million) trees—to make way for roads, runways, and concrete. These are not secondary or degraded forests; they are primary tropical ecosystems that have evolved over millions of years and form part of the globally recognised Sundaland biodiversity hotspot.

The government’s proposal to “compensate” by planting trees in Haryana—thousands of kilometres away and in a completely different ecological zone—is scientifically ludicrous and morally cynical. As one ecologist observed, it is like demolishing the Taj Mahal and promising to build a replica in Gujarat.

The biodiversity losses will be catastrophic. Galathea Bay, where the port is planned, is among the world’s last major nesting sites of the critically endangered leatherback turtle. Dredging for the harbour will displace silt, suffocating coral reefs and seagrass meadows that sustain marine life. On land, the Nicobar megapode, tree shrew, flying fox, and crab-eating macaque—all endemic species—face extinction. Numerous endemic plants, some yet unrecorded by science, will vanish before they are named.

These forests also provide indispensable ecosystem services—carbon sequestration, water regulation, coastal protection, and climate moderation—that never appear in official economics but are vital to human survival. Destroying them releases vast quantities of stored carbon, destabilises rainfall, and erodes natural barriers against tsunamis.

The economic value of these services far exceeds any potential revenue the port might yield. But since they are “free” and not monetised, they are treated as expendable.

The Tribal Genocide

The Great Nicobar project imperils not only biodiversity but entire human cultures. The island is home to two indigenous groups—the Nicobarese and the Shompen—whose lives are inseparable from the forests that sustain them.

The Shompen, numbering fewer than 300, are among the world’s most isolated peoples, classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). They are semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, with little immunity to common diseases and minimal contact with outsiders. Their survival depends entirely on forest resources and social isolation. The Nicobarese, though somewhat integrated, also depend on forests and coastal ecosystems.

The influx of 3.5 lakh settlers will obliterate their world through displacement, disease exposure, loss of resources, and cultural assimilation. Even if physically undisturbed, their food sources and social fabric will collapse. Experts from Survival International and other bodies have warned that the project could lead to the extinction of the Shompen people. This is not alarmism but a sober reading of global history: isolated tribes rarely survive forced contact with industrial civilisation.

Legally, the project violates every protection guaranteed to tribal communities. The Forest Rights Act (2006) mandates their free, prior, and informed consent. The PESA Act (1996) requires consultation for development projects in scheduled areas. Even the Constitution, through the Fifth Schedule, safeguards tribal lands from exploitation. All these provisions have been bypassed through procedural manipulation. Public hearings were held without proper notice, in languages the tribes do not understand. Institutions tasked with protecting the environment and tribal rights were sidelined. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs’ warnings were ignored; the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes’ concerns were brushed aside.

In the Modi government’s vocabulary, dissent equals sabotage, and ecological caution equals anti-nationalism. What is unfolding is not development but state-sponsored cultural genocide, conducted in the full knowledge of its consequences.

The Seismic Insanity

Equally alarming is the site’s geological vulnerability. Great Nicobar lies directly above the convergent boundary of the Indian and Burmese tectonic plates—the same fault that triggered the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, killing over 230,000 people. The island’s coastline was permanently altered; entire settlements vanished.

Building ports, power plants, and an urban settlement for 350,000 people on such terrain is reckless to the point of criminality. Recent seismic activity around the Nicobar Islands, including clusters of small quakes and warnings of possible volcanic disturbances, underline the continuing risk.

No credible evacuation or disaster-preparedness plan exists for the projected population. Even if technically possible, safeguarding such a massive settlement against earthquakes and tsunamis would require astronomical costs and still offer no real safety. The government is gambling with hundreds of thousands of future lives for the sake of a vanity project.

The project’s approval process exposes the authoritarian tendencies that have come to define governance under the current regime. Environmental clearances that should have taken years were granted in months. Public consultations were perfunctory; scientific objections were buried. The Expert Appraisal Committee and the National Board for Wildlife—statutory bodies meant to safeguard the environment—became rubber stamps.

This pattern—announcing mega-projects, fast-tracking approvals, and criminalising criticism—defines the regime’s model of governance. It privileges optics over substance, authoritarian efficiency over democratic deliberation, and propaganda over prudence.

Developmental Hubris and the Long-Term Losses

Beyond moral and ecological devastation, the project entails immense long-term costs that no economic calculus acknowledges.

Scientific and Medical Value

The forests of Great Nicobar represent an irreplaceable repository of genetic diversity, shaped over millions of years of evolution and isolation. Scientists estimate that tropical rainforests harbour up to half of the world’s terrestrial species, most of them still undescribed. Each species is not merely an ecological ornament but a potential source of biochemical innovation. Humanity’s pharmacopeia—from quinine, derived from South American cinchona bark, to vincristine and vinblastine from the Madagascar periwinkle used in cancer therapy—owes its breakthroughs to precisely such environments. The rainforests of Great Nicobar, lying within the Sundaland biodiversity hotspot, may similarly contain compounds with antiviral, antibacterial, and anticancer properties yet undiscovered. Their loss would mean the erasure of an entire molecular library before science even reads its first page. The island’s unique fauna—its crab-eating macaques, Nicobar flying foxes, and tree shrews—are of exceptional evolutionary interest; their extinction would permanently foreclose avenues for genetic and biomedical research that could benefit humankind. In an age when pandemics remind us how fragile our biological security is, destroying one of the world’s richest natural laboratories is an act of collective folly.

Ecological Debt

We are, in essence, liquidating millions of years of natural evolution to underwrite a few decades of speculative growth. Once these ecosystems are destroyed, they cannot be recreated by human ingenuity or afforestation schemes. What takes nature millennia to weave—the symbiosis of soil, species, and climate—is unravelled in months by bulldozers. The loss is not just ecological but civilisational: a depletion of the Earth’s living capital that future generations will inherit as ecological debt. This debt accrues silently, through eroded coastlines, altered rainfall, and vanishing biodiversity, yet it compounds faster than any fiscal deficit. The true cost of Great Nicobar will thus be measured not in rupees or dollars, but in the diminished inheritance of those who come after us—a planet stripped of its biological imagination.

Economic Irrationality

Even on narrow fiscal terms, the scheme is deeply indefensible. The project’s headline cost is commonly reported in the range Rs 72,000-81,000 crore (roughly US$ 9-10 billion). The port component alone is being planned with a total capacity of up to 16 million TEUs (with Phase-I capacity often cited at four million TEUs). By contrast, established regional hubs already dominate: Singapore handled 41 million TEUs in 2024; the Port of Colombo 7.8 million TEUs in the same year. Independent observers and conservation experts warn that the capital cost is likely understated and the risk of remote-location, earthquake/tsunami-vulnerability and operations in an untested environment is likely vastly under-accounted; at the same time, the revenue assumptions are widely regarded as optimistic given entrenched market shares of Singapore and Colombo and the many other new terminals emerging. Put bluntly: spending Rs 75,000 crore to build capacity that would still struggle to match throughput of existing regional players, while incurring steep yearly operating and disaster-resilience costs, is unlikely to produce revenues that even approach payback—let alone offset the irreversible ecological and social losses.

If India genuinely requires additional port capacity or strategic presence in the Andaman-Nicobar region, alternatives exist. Mainland ports such as Vizhinjam, Ennore, or Paradip could be developed at far lower environmental cost and greater economic sense. Military infrastructure, if necessary, could be strengthened on already disturbed terrain without annihilating primary forests or indigenous cultures.

But exploring alternatives demands rational policy-making, scientific humility, and moral restraint—qualities that the current developmental ethos dismisses as weakness. The regime equates scale with strength and concrete with modernity, blind to the long-term ruin it bequeaths.

A Test of India’s Soul

The Great Nicobar project is not merely an environmental issue; it is a moral and civilisational crisis. It asks what kind of nation India seeks to be: one that bulldozes ancient forests and exterminates fragile cultures for illusory gains, or one that measures progress by its capacity for restraint and stewardship.

To proceed with this project is to enshrine ecological destruction and cultural annihilation as instruments of national pride. To abandon it is not to oppose development—it is to affirm sanity, science, and the sanctity of life.

A truly developed nation is not one that builds the largest ports or airports but one that protects what is irreplaceable. The forests of Great Nicobar, the leatherback turtles of Galathea Bay, and the Shompen people cannot speak in policy meetings or courtrooms. They depend on our capacity for reason and compassion.

If this project continues, India will have committed an irreversible crime—against nature, against its own Constitution, and against future generations. It is still possible to stop this catastrophe, to choose deliberation over destruction, and to show that development need not mean devastation.

History will remember the choice we make.