"We've a vast tradition of nude pictorial depiction. In fact, it's what we study."Vivan Sundaram

***

Is it a coincidence that every time the Narendra Modi government finds itself in hot water, a saffron-tinged 'cultural' issue crops up that helps divert attention from its troubles? The saffron brigade's assault earlier this month on the Fine Arts Faculty, MS University, Baroda, provided a timely diversion for the Gujarat dispensation, under fire for the Sohrabuddin fake encounter case. The architect of the May 9 attack was Niraj Jain, a VHP-Bajrang Dal activist, and his target, 23-year-old final-year student Chandramohan Srimantula, a Lalit Kala award-winner.

It was upon being tipped off by a local journalist that Jain and his saffron stormtroopers descended on the Faculty and vandalised Chandramohan's works, on exhibit for an examination assessment. They claimed his artwork, of religious images with anatomical details, was obscene and offended their religious sensibilities. The police arrived and arrested the student, who was charged with being a threat to peace and communal harmony. He spent four days in the lock-up before the judge ruled that his intentions were not malafide, he posed no threat to public peace, and let him off on unconditional bail.

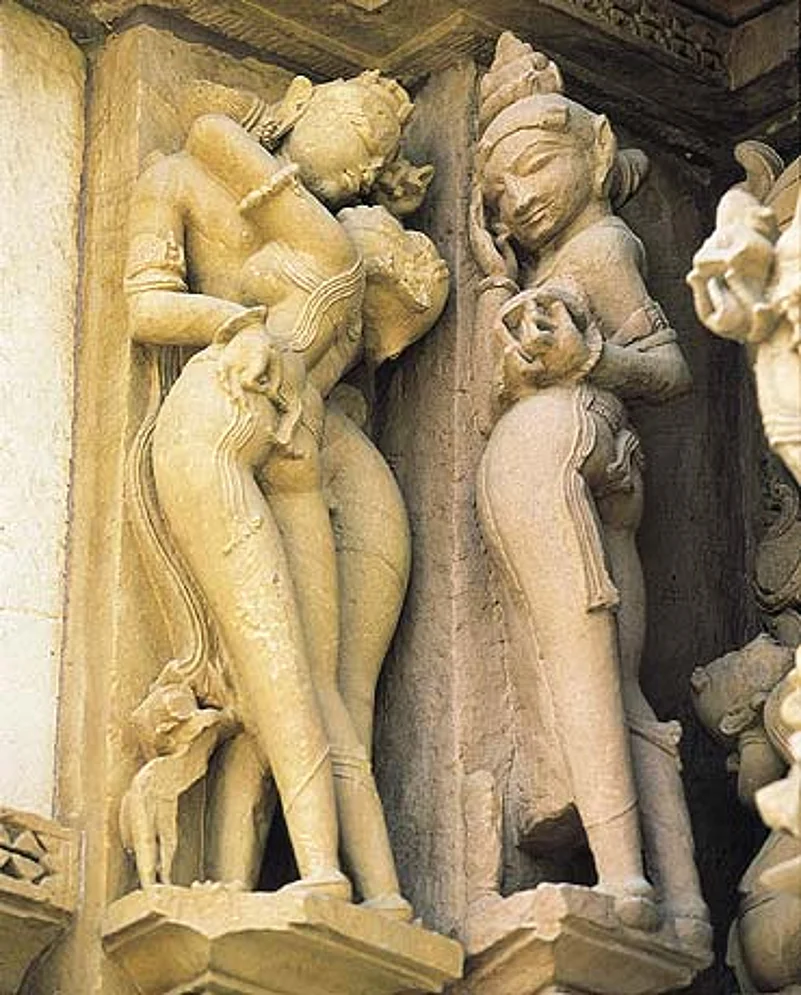

An amorous couple sculpted in a Khajuraho temple

Students and lecturers from the fine arts department, outraged by the arrest, protested by putting up an exhibition of Indian erotica, which was again disrupted by BJP councillors who arrived on the scene to hurl abuse at students and lecturers. MSU vice-chancellor Manoj Soni then demanded that the dean, Shivaji Panikkar, remove the exhibits. Panikkar refused, following which Soni suspended him and, aided by colleagues and BJP councillors, removed the exhibits and sealed the department.

Though the vigilantism of BJP goons had the state education minister Anandiben Patel's approval, MSU alumni, teachers, artists and intellectuals across the country voiced their unanimous outrage at the incident. Eminent Baroda-based artist Gulammohammed Sheikh said, "In a civilised society, any dispute or a controversial depiction or content of a work of art can be dealt with through dialogue and consultation with experts in the field, rather than be left to self-appointed moral police employing coercive means."

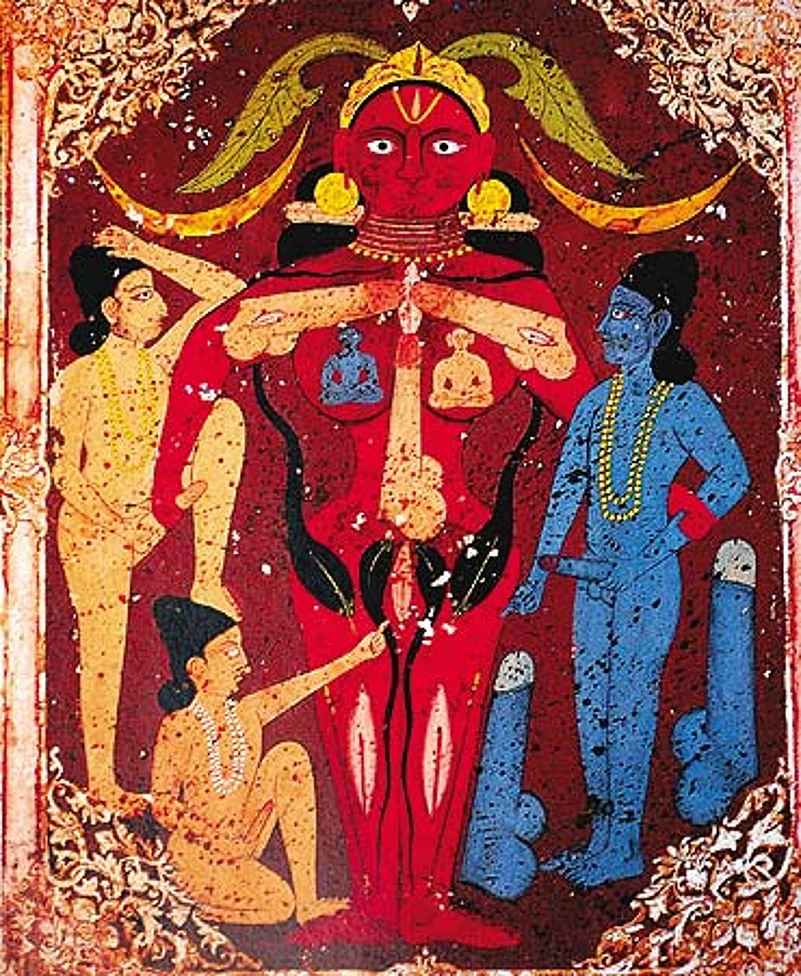

an 18th-century Rajasthani image of nude male devotees surrounding the personification of the female principle in the form of the goddess

Protests against the student's arrest and the suspension of the dean were held simultaneously in ten cities on May 14. Members of the public, including artists and activists, gathered to assert the right to free speech and expression, as well as an artist's licence to sample from and extend tradition. Artist Vivan Sundaram, an MSU alumnus himself, was among those who addressed the Delhi protesters. He later told Outlook, "We have a vast and graphic tradition of nude and erotic sculpture and pictorial representation. When I was a student there, we had hundreds of plates made of these images. It's what we studied. All artists begin from tradition."

Folk artists are equally incredulous. "I told the story to a group I work with, including Kalamkari and Patachitra artisans who spend their life making iconic images of Hindu gods and goddesses," says Laila Tyabji, chairperson of Dastkar, a society for craftspeople. "One explained that the depiction of love in painting and sculpture is 'an expression of the cosmic life force, not pornography', while the other said 'goddesses have only been clothed since the advent of movies and TV serials'." Artist Anjolie Ela Menon made a similar observation: "It is only since Raja Ravi Varma started clothing gods and goddesses in the vestments of his own times that the prevailing sense of prudery began to take root."

terracotta images of fertility goddesses, 4th-6th century

But while the erotic tradition provides inspiration to contemporary artists, it also implies limits to how they may use it. Asks Dr Madhu Khanna, professor of Indic Studies at Jamia Millia Islamia: "How far does an artist have the freedom to replace, distort, reconfigure religious imagery evolved over 2,000 years?" She believes that artists who use the ancient erotic tradition to fuel their work must also be sensitive to its conventions. "Erotic icons are not individual creations—they are created by parampara (tradition)," says Khanna, "Their depictions are based on a code of iconography."

The problem with translating erotic images from a traditional, devotional context to a modern, secular context is the absence of such a code. "Traditional art has a ritualistic canon," says well-known art historian Yashodhara Dalmia. "Contemporary art, strictly speaking, doesn't have any regulations."

Art critic and curator Alka Pande believes contemporary art has often more to do with irreverence and sensationalism, with being provocative. "These are things that have to be questioned. You cannot just use floating penises or demons coming out of a Mahakali, unless you are making an informed reference," she adds.

Actress Nandita Das at a protest meet in Delhi on May 14

So, while experts unanimously condemn the VHP's brute censorship, they also believe there are limits to artistic licence, defined by ethics and the artistic tradition, rather than the opinions of a religious fringe. And even if these limits are not heeded, there is place for criticism and correction. "A young person's art—I won't say it's great art—but we must allow students to explore, to make mistakes, that's how every generation finds new forms of expression," says art historian Shobita Punja. Adds artist Jehangir Sabavala: "It was for his professors and examiners to judge the work of this young artist, not for someone to barge in from outside and push him into jail. It's all heavily politicised."

"Criticism should be the domain of enlightened people," agrees Pande, adding, "possibly the judiciary." Or more appropriately, the professional critics, teachers and historians of art, who have been trained to understand our artistic tradition and to know when an artist has deviated from it.

"Our problem is that we have thousands of artists, and no critics," Khanna laments. "We need strong critics who are educated, cultivated and sensitised to their roots." Until then, the monopoly on art criticism seems to be in the grip of the least cultivated among us—politicians and goons.