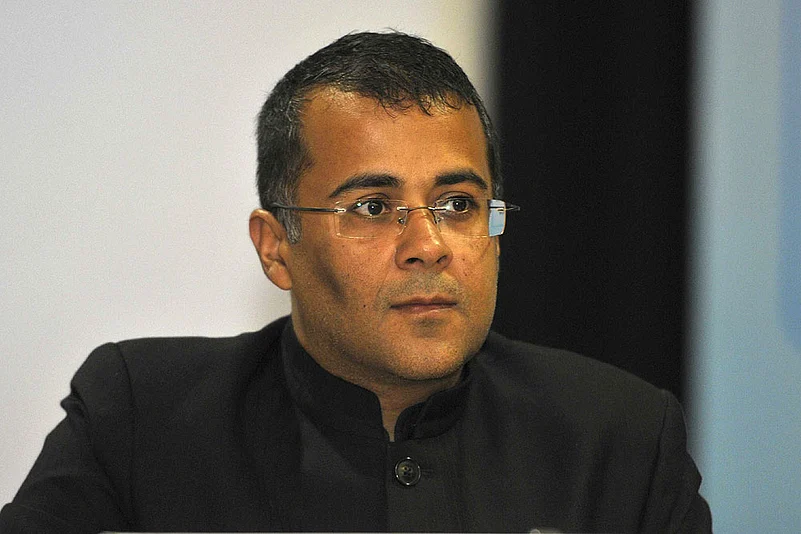

I write this as a teacher in Delhi University and as an elected Academic Council member. There was a time when university elitism was gently lampooned in a famous limerick, which said of an English paper that “Shakespeare answered very badly/Because he hadn’t read his Bradley”. In a less gentle vein, people have for years been asking what relevance Chaucer or the Silver Poets have. But it’s time to forget the notion that education may have to do with something you didn’t already know about—opening up a whole history, a world of aesthetics, and questions of power. We are now blithely going pop. Chetan Bhagat is in the syllabus.

A few points, humbly submitted. One, yes, it’s a proposed syllabus still, not an adopted one. And yes, it’s not quite true that Chetan Bhagat has replaced Tagore and Amitav Ghosh. He comes in as part of an elective paper on popular fiction, offered to honours students from outside literature. Tagore and Amitav Ghosh have only been dropped from the core literature courses. Tender mercies. Ghare Baire (The Home and The World) has been excised outright. The Shadow Lines has been banished to a place befitting its title—an optional paper on Partition literature.

Two, this proposed syllabus emerged from an exercise without even minimum consultation with teachers—thanks to the exigency/emergency Delhi University has been thrown into for some time (those who have followed the semester, FYUP, CBCS travails would understand). The committee that suggested this was formed in secrecy, without statutory sanction, and is non-representative if you look at the diversity of institutions/teachers imparting education in English Literature in DU.

Three, on page 42 of the proposed syllabus, where Bhagat is included, you find the title of the paper and four texts listed out. Nothing else. When you frame a syllabus, especially at the undergraduate level, you provide a framework to study the texts, without which it makes no sense. You can include Mein Kampf as part of a paper on Autobiography or Fascism or, if you go by the current trend, Nationalism, but you have to propose a methodology of analysis/study. Once it is there, one can, of course, limit oneself or go beyond those frameworks in the classroom.

Four, I am not against ‘popular literature’. In fact, as a teacher, I am concerned with understanding how something is popular and something else is not, while trying to critically expand the limits of ‘literature’. With Chetan Bhagat or without him in the syllabus, many of us try to locate the intersections of art, commercial success, canon formation and youth culture on our own. In fact, I hear there has been an excellent MPhil dissertation in DU that critically compares the fiction of Amitav Ghosh and Chetan Bhagat.

Therefore, this is not about any one book offered by a single teacher to a small set of students. When adopted, it will be taken up in 70 colleges by thousands of students. And, if you care to understand the subterfuge of the CBCS model-syllabus, adopted with extremely restrictive stipulations by the UGC two years ago, you will realise the imminent danger. The DU syllabus, sans any critical framework, may again be verbatim copied as the national model, seriously compromising academic rigour, while unleashing the entire political economy of ‘kunjification’ (guide notes industry).

Five, Chetan Bhagat is the Chetan Bhagat of today only because English is not just a language in our society; it is power, access, privilege. It is a caste that makes many unspeakable and marks many as untouchable. The aspirational value attached to it is central to his being a cause celebre, along with his ability to please political authority of the governing kind. His English is read as ‘literature’ because of the deficit/surplus of English ensured by India’s ruling system.

I bring him to my classroom even without having his book prescribed; I subject him not to the scorn of the elite but of the educated (I don’t mean ‘university-educated’, but, if I may say so, socially-politically educated). His ‘acceptance’ speech/posts/tweets after the ‘inclusion’ in the syllabus—self-congratulatory, scornful, imbecile—is familiar to me due to the many classroom vivisections of ‘popular’, ‘literature’ and ‘popular literature’ I am habituated to.

Six, and this is my coda. Chetan Bhagat as a public entity is humongous in the market, utter trash as a writer and, as an intellectual, non-existent. If not gold, he’s quicksilver—in a matter of a day, he first Twitter-bowed to DU teachers for his inclusion and then tele-bashed one such teacher for a critical view. The academia should certainly devote itself to some extent to understand his persona and psycho-social impact.

Bring him on, I say, though preferably not at the UG level, but always with conceptual frameworks and critical modes to denude and detoxify his misogyny, platitudinal, stereotyped effulgence, and locate him and his commercial success in a deeply unjust society that abounds with enforced illiteracies. In the meanwhile, please understand that the fight in DU is not only about him, your views on literature or mine, but about institutional responsibility, procedure, transparency, democracy and academic rigour.

(The writer teaches English at Dyal Singh College, DU)