The regulations aim to prevent discrimination based on caste, gender, religion, disability, and place of birth, in line with constitutional principles.

Opposition by some upper-caste groups reflects entrenched anxieties over representation and perceived loss of socio-cultural dominance.

Provisions like Equal Opportunity Centres and Equity Committees seek to ensure fair participation for marginalised communities in institutions.

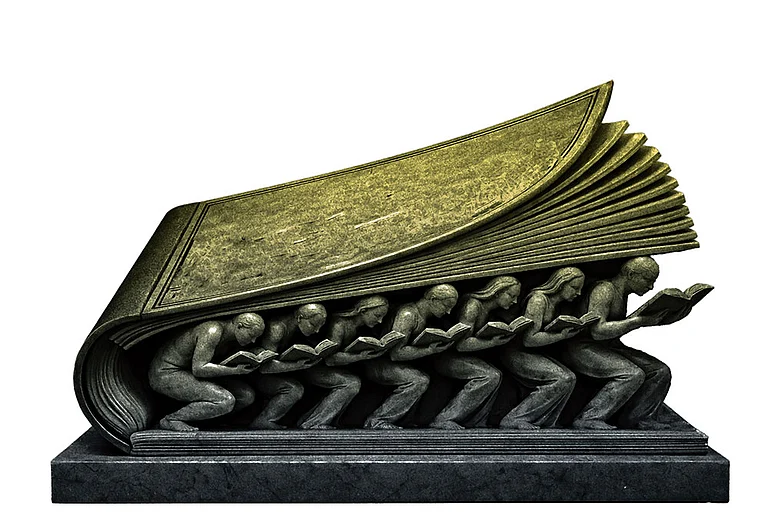

The Socio-Cultural Debate Over The UGC’s Equity Regulations

UGC’s 2026 equity regulations expose persistent caste and social divides in higher education.

The Supreme Court has stayed the University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulation, 2026. The regulations were strongly opposed by several savarna (upper-caste) groups across the country. Soon after the January 13 notification, several savarna groups organised large-scale protests.

Disagreements with government regulations are not unusual. However, the protests this time reveal a deeper social and cultural divide, which is particularly concerning.

It’s unfortunate that some individuals resorted to casteist attacks on social media, even targeting the country’s Prime Minister.

The UGC regulations provide guidance toward controlling discrimination in educational institutions. They aim to prevent discrimination in institutions based on religion, race, caste, gender, place of birth, or against persons with disabilities.

This aligns with the spirit of the Constitution. However, the controversy arose, while defining the word discrimination in one of its clauses, the UGC mentioned Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC) under the category of “caste-based discrimination.” The opposing side interpreted it to mean that “general category” or upper-caste groups were being seen as oppressors.

According to them, this regulation inherently portrays upper-caste individuals as accused and creates the possibility of misuse. Based on these concerns, the Supreme Court put a stay on the regulation.

The opposition reflects deeper socio-cultural anxieties around caste and representation.

The UGC regulation were aimed at addressing entrenched anti-equality sentiments and guiding educational institutions toward fairer practices.

The provisions in this regulation were supported by factual evidence collected by the UGC. The UGC informed the parliamentary committee and the Supreme Court that there had been a 118 per cent increase in cases of caste-based discriminatory behaviour in educational institutions.

A similar kind of opposition was also seen when, as the Law Minister, B. R. Ambedkar proposed the Hindu Code Bill on the floor of parliament. The aggressive resistance to the Hindu Code Bill reflected an attempt to preserve a conservative social order rather than uphold constitutional values. The bill was related to the rights of Hindu women, yet a section within Hindu society opposed it by claiming it would lead to the “destruction of Sanatan Dharma.”

When Jawaharlal Nehru withdrew the bill, the editorial of the mouthpiece of Arya Mahila Hitkarini Mahaparishad described it as the “victory of divine forces over demonic forces.”

Directly or indirectly, such ideas express caste dominance in the name of religion and culture. However, society must move beyond old conservative ideologies and progress along the constitutional path. This has also been the guiding idea behind the UGC regulation.

When the UGC regulations are viewed in its entirety, it does not appear to be indifferent toward any group. In the objective of the regulation itself, the context of eliminating discrimination based on religion, race, caste, place of birth, and disability have been included along with SC, ST, socially and educationally backward classes, and economically weaker sections. The opposition regarding Point 3, Part (C) of this regulations appear to be based largely on assumptions.

In this regulation, the appointment of a coordinator for the “Equal Opportunity Centre” and the formation of an “Equity Committee” do not reflect any intention of expressing discrimination against anyone.

It is also inappropriate to allege discrimination based solely on the inclusion of certain reserved groups in the Equity Committee under point 5, Part (7) of the regulations.

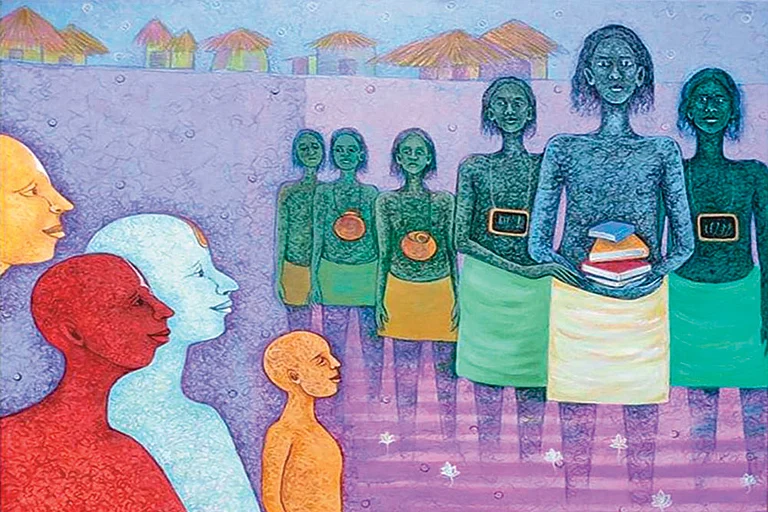

In fact, such provisions emerge from patterns of social neglect, due to which representation of deprived groups often fails to emerge within institutions. Even today, adequate participation of deprived and backward classes has not been fully ensured in central institutions. Incidents such as NFS (Not Found Suitable) in appointments and promotions in educational institutions have so far largely been linked with these very groups. Therefore, it does not seem reasonable to claim that this regulation inherently treats the general category as accused.

There can be possibilities of misuse of any legislation, and such possibilities may also exist in reality—but that is a separate matter, and it should be regulated. However, rejecting a policy solely on the basis of assumptions and speculation lacks logical soundness.

Our society has yet to overcome caste-based structure. Government data itself bears the testimony of caste-based discrimination.

Recently, a student from Tripura, Angel Chakma, was killed in Dehradun based on racial discrimination. Such incidents often receive attention only posthumously. Members of marginalised communities mostly endure discrimination silently, which often goes unrecorded. Provisions such as Equal Opportunity Centres or Equity Committees are necessary for this purpose. Differences of opinion on such issues are natural, but we must move toward a new future grounded in constitutional values.

If the UGC regulation were reversed under similar pressure, it would be unfortunate and underscore the ongoing challenges faced by marginalised communities in accessing equal opportunities.

Anuj Lugun is a contemporary Hindi poet from Jharkhand known for his writings on Adivasi identity and resistance. He is a recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar.