Youth in Taloja Jail face neglect and despair behind iron walls.

Solitude and systemic failures quietly erode prisoners’ mental and physical health.

Hope fades as corruption and indifference shadow daily life in prison.

Taloja Jail: Lives Fading in Silence Behind Iron Walls

The author, who spent 10 years in jail, details the painful experiences of the inmates and the cold attitude of the authorities

Narya was a prisoner in Taloja Central Jail, Navi Mumbai. He was young and had already spent a few years in jail. With overgrown hair, a thick moustache and a full-grown beard, he was an eccentric who would roam the prison yard with complete disregard. Since he routinely got into quarrels with the jailer and physical fights with other inmates, people were wary of him. Otherwise, he would get along well with other inmates. Once, he hit a jail superintendent on his face, after which the jailers mercilessly tortured him by resorting to nalbandi—where the prisoner is made to lie flat on the floor with his feet hooked to the iron bars of the prison, his soles are then relentlessly beaten with a baton.

He was declared “mental” (mentally unwell), and pumped with “mental injections”. He was thrown into solitary confinement. Because of his fortitude, jail officials did not antagonise him much. The careless pumping of medications into his body and the solitary confinement took its toll on his state of mind, deteriorating it further. He was afflicted with tuberculosis and was admitted to the prison hospital. He had been accused of rape, but was not convicted due to stagnant court proceedings. Communication with his family was sporadic. He was practically living off ganja and developed severe mental health issues. He was returned to the circle—one of the five enclosed buildings housing 500-550 prisoners each in Taloja Jail. Narya ended his days in this pitiable state as a mental health patient in the prison hospital in 2024.

Ramesh Salunkhe, Circle No: 3; Barrack No: 8

One night, Ramesh Salunkhe sat at the foot of my bed and said, “Sir, I need to tell you something important. In our tribal hamlet (Mangao), minor girls are being trafficked. A huge racket is underway. A young girl from my family has also been dragged into it. I will give you the phone number. Please try to free those girls once you get out.” “One more thing,” he pleaded. “Sir, can you have someone from your legal team to represent me? That way I can get my trial started.”

These are some glimpses of my conversation with the youth. I spent the last seven months with the young man. I was part of his handi, the secret meal preparation set up by the prisoners to compensate for the substandard prison meals. He was our barrack leader, extremely sociable, but also strictly disciplined. He had the art to ensure all barrack members did their assigned tasks. A multitalented artist, skilled artisan, and worker, he was accused of crimes under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012, (POCSO).

His family background was that of extreme poverty. That’s why his dream of getting out of prison, marrying his beloved, and living happily had slowly eroded and vanished. The prison walls had crushed his romantic fantasies. Three years passed. As more doors to get out of prison shut on his face, his behaviour started getting edgier. When the silent turmoil inside him would erupt, he would shout obscenities or would just stay mum or wrap a bedsheet and sleep. For the same reason he took up smoking ganja—going to any length to acquire it. For years he had neither seen the world outside, nor had he seen his mother and brother. He never received a money order.

Is there no freedom and justice for the prisoners? Do the “people of India” become outsiders once they are accused of a crime?

All this made him completely dependent on ganja. His routine was to stay up past midnight and sleep during the day. The Ramesh, who in the beginning would diligently undertake arduous exercise sessions, had started wasting away, completely demoralised. No contact from home. No one trying to get him out of prison. As his dream of getting out was shattered, he was mentally disturbed. He also developed severe psychological issues. He caught a fever and was constantly battling it for 2-3 months. He did not receive appropriate treatment. He had lost all hope to live. Consequently, he stopped eating. One night, he fainted on the bed. He was admitted to the J. J. Hospital, but he died there 15 days later. I received this news early morning when we were let out of our nightly lockup. I was left stunned. This event took place in December 2024.

For Taloja Prison—as is true of most prisons in Maharashtra—these kinds of frequent deaths raise questions about our criminal justice system. Completely healthy individuals, full of vitality, collapse all of a sudden… are finished… but the prison administration remains indifferent. This complacence has created a catastrophic problem of prisoners’ mental and physical health. The atmosphere in the prison without autonomy, justice, social belonging, and with ramshackle medical services and inhumane treatment is lethal for the prisoners’ mental health.

Mental Health Problem? “Ram Bharose!”

There is only one psychiatrist in the Taloja Central Jail, and even she does not work full-time. Normally, the prison has one or two counselors, but they are not enough to serve the needs of thousands of prisoners. At present, the psychotherapists serving in the prison aren’t even adequately trained. The Taloja Central Jail does not have an MBBS doctor or surgeon. All the five doctors appointed are Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery (BAMS). Even the chief medical officer (CMO) only has a BAMS degree. There is no separate ward or even nursing staff or caretaker for people with mental health issues. That’s why prisoners do not receive appropriate mental health support. Other medical issues, at least, receive medications, but that is not available for mental health issues. Only sleeping pills are handed out for such problems! Even if you ask them [medical staff] to visit you, one cannot find out the exact diagnosis of the psychological conditions. For serious psychological issues such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and emotional trauma, there is no avenue to seek psychiatric care in a hospital. Counselling is out of the question; even sympathetic communication with the afflicted is absent. They are labelled “mental” and derided. Their self-esteem, dignity, and human rights are trampled upon. This cruel and inhumane treatment ensures that a person is driven to “madness”, as it is labelled. There is no sympathy, sensitivity, friendliness, humanity, or even a kind word for them. There are no reformative activities. Some prisons run educational programmes, skill development, and entertainment programmes, but these are limited in nature. Even then they are mostly a publicity stunt for the officers. There is a severe lack of stress relieving measures.

Under the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, each prison in India must ensure mental healthcare and support. Not just the Taloja Central Prison, no other prison in Maharashtra has ensured the complete implementation of this law. In Maharashtra this law is disregarded. There is no mechanism to enforce it. This agony never reaches the judiciary. Even if it did, it would only lead to tarikh pe tarikh (endless court appearances). What is happening federally to the constitution is happening at the prison level to this law.

The Factory Churning out Mental Health Problems

“Ae malik tere bande hum,” (as the faithful) is how people approach the doctor, but the doctor says, “Just do meditation.” But there is no quiet. A barrack meant for people is filled with 40-45 people! The harsh atmosphere of the prison, lack of freedom and justice, lack of social contact heightens the depression, anxiety, and the stress of the prisoners. Prolonged legal procedures and solitary conditions lead to several mental health issues. Due to not receiving appropriate counselling on time, incidents of suicide among prisoners are on the rise. Without mental support, a number of prisoners feel restless, irritable, stifled, disinterested, hopeless, intolerant, angry, aggressive, and entertain suicidal ideation or murderous thoughts. Something feels amiss between the mind, body, and the rest of the world.

This constant restlessness creates an embittered dysfunction within an inmate. They are losing their mental balance. Being imprisoned, they lack control over their situation. They cannot think straight. As a consequence, resorting to intoxicants, superstitions, apathy, insensitivity and instability becomes more likely. The damaged, unstable self keeps bursting out. Some are scared, some delusional, some irritable while others are constantly shrouded in a cloud of depression. Some are extremely talkative like Lucky from ‘Waiting for Godot’ or utterly silent. The situation gets out of control and the mind starts cowering. It is true that the country’s miasmic air also flows freely through the prison.

The average age of the people incarcerated in the prison is around 26-27. Most people are from the age group of 20-40. At least 94 per cent of prisoners are undertrials. In Maharashtra, the number is 84 per cent, while countrywide, it is 75 per cent.

About 75 per cent of them had been working, while those under the age of 18 and outside the prison—had not cleared their 10th board exams. The youth of the country is wasting away in the prisons. The aged are increasingly being afflicted by psychological issues while the youth is drowning in intoxication. Dalits, Adivasis, and Muslims are twice more likely to be imprisoned than their representation in the entire population. All kinds of disparities are growing in our society. The rich are getting richer; the poor are getting poorer. The one per cent minority has stolen 40 per cent of the country’s wealth, while the majority of the population is thrown into an abyss of misery. This so-called development is being done in broad daylight in blatant disregard of the Constitution. Access to not just power, property and rights, but also to education and health, is vastly unequal among this majority. Most of them are poor, oppressed, exploited, half-literate, and desperate, and hence, are considered thieves. The oppressors, real thieves wear suits and blazers and so their wealth is legitimate. Justice is on sale in this country. Seldom is it generous with the poor. That’s the reason you won’t find any counsellors for legal matters of poor prison inmates. That is why there won’t be anyone to help with their deteriorating mental health. And that is why they are blowing away their life in prisons.

The architecture of this prison building is depressing too. Even more depressing is to be forced to look at the inmates in the barrack opposite you after the lock-up. The triggers to traumatise someone are built into the building. There is no soil for your feet to touch, much less for trees to grow. No flowers. No greenery. No good smell. No breeze. Where would one find vitality? How will one breathe? As a result, a person wilts from within before dropping down like an autumn leaf.

There is also an extreme scarcity of water (water is for sale in prison). Without water, your decent healthy body starts smelling. If it rains, the roof leaks. Each prisoner gets one or at best two buckets of water every day. Of that, how much to allocate for drinking, and for bathing, or to wash clothes or use for the toilet or to clean dirty dishes after meals. The toilets are all clogged without water. The drains overflow with human excreta, layers of bidi and cigarette buds, and a thick red layer of spit tobacco. The wet waste and leftovers are dumped in the barracks and left to rot. It makes you throw up.

The rotten smell stings your nose. Your head hurts. Just filth everywhere. Odour, mosquitoes, malaria, dengue, flies and skin diseases rule. Meals must be had in the same filth while trying to get rid of the flies. You must sit there. Sleep there, uneasy and cramped among so many people. Of course, the filth in toilets and drainages is left to be cleaned up by people from a specific caste or community. Look at this prison of caste and caste in prison! It drives you mad. Whereas, the jailer and guards are living a luxurious life full of Pepsi, Coke, sweets and namkeen at the cost of the inmates, and on top of which, they will look at the prison inmates with disgust and say, “You guys are lucky. The government is providing you with free food and shelter.” And these petty tyrannous Neroes, sucking the blood of the inmates at every step, stand in crisp uniforms to make a grand salute to the flag on Independence Day! A microcosm of what happens at the Red Fort!

A strip search is conducted upon entering the prison. Self-esteem is crushed, the prisoner is humiliated. From the get-go, there are fights over space, water, over drying clothes or over bedding. It becomes a daily drama. Queues for water in the morning. Queues to wash your clothes. Queues to cut your hair and nails. Queues for the toilet. Queues for tea, breakfast, lunch and dinner. Queues for the canteen. Queues to meet your family or lawyer. Queues for treatment. Queues for your court dates. Queues for justice. Longest queues for smallest things. If you break the queue, you get a whack on the back. Three chapatis of such low quality that even a dog would not eat, tasteless subji, some questionable thing that floats on the daal or the subji, but there’s no other option but to eat it. And the officers and administration make sure the meals remain substandard so that they can sell good quality meals to richer inmates in the black market. The canteen inside the prison serves as a shop for the inmates. It is supposed to provide essential things to the inmates on a no-profit-no-loss basis. But the jail authorities hike up the prices of the goods and earn in lakhs. There is a complete bottom-up chain of these illegal earnings all day, every day. The Directorate of Enforcement (ED) is unreachable here.

They create a false scarcity of beddings for the inmates like a streetside market, and then sell them for up to Rs 10,000. A bed for Rs 10-150,000; Rs 10,000 to appear for a court hearing; Rs 150,000 if you need to go to an external hospital; Rs 20,000 if you want to make a particular meeting happen; Rs 1 lakh per month if you want delicious meals for a whole month; and, Rs 1 lakh if you want to chat to your heart’s delight on a video conference. The jail has become a hotbed of scammers and thieves. It’s all pleasure for the rich prisoners, but more than a punishment for ordinary inmates. The whims and cravings of the richer inmates are satisfied at the cost of poor inmates’ ration and rights. But you can’t really say anything against it because the jail is still under the terror of angrezon ke zamaanein ka dandaa (unreformed remnants of British justice).

The human brain gets fried because of the constant fear, stress, violence and uncertainty in the prison. Slavery is normalised. The slow poisoning seeps into the veins. The inmates become robots. They start working mechanically to the clock. The prison keeps running on their free labour. The remaining ones march on the beat of a fascist drum. Say “Jai Hind” out of fear. This is double confinement. First upon the arrest, then upon entering the prison—individual freedom is destroyed.

Freedom Starts Where Fear Stops…

Humans are born free individuals. But freedom has cast a web of fear around us. Our culture lures us with false, hypocritical words, but its foundation is that of fear and exploitation. Cultural subjugation maintains complete control over brains, minds and thoughts, resulting in complete submission. Under this cultural subjugation, a person, far from figuring out what subjugates her/him, can barely realise she/he is subjugated in the first place. That is why a “Jai Hind” salute coming from an inmate’s mouth is an inevitable expression of his destroyed sense of self. There is fear everywhere, inside and outside of the prison—the fear of caste, religion, law and fines, power, prison, discrimination and poverty. This very fear erodes a human being’s self and a person is made a stranger to freedom.

Additionally, the inmates are deprived of their mother’s affection, siblings’ love, father’s support and friendships. Supportive words are unheard of, a caring touch is missing. Neither a happy moment nor a cathartic cry! No overwhelming moment of trust, no silent communication through the eyes. An invisible fear is always around, chasing us. This perpetual fear curdles every feeling, every trauma, every mindset, poisonously planting it into the body. The inmates forget their voice. Their words. Their expression. The sense of self will be destabilised, and mental health will suffer, the brain and body will suffer if feelings, trauma, disappointments, pain, complications of health and relationships, desire, aspirations and dreams are not let out. And it is this thwarted expression of creativity that creates psychological health issues.

The whole prison becomes an asylum ward. I’ve lived and breathed in this asylum ward for 10 years. I’ve seen people die in front of me. I’ve seen them grasped by mental afflictions. I’ve seen them staring into the void and mumbling incoherently. But I was always hopeful. I was full of thoughts. I believed in the pains of the Dalits and the labouring classes. My own life had, in a way, merged with their existential hardships. A political prisoner always knows that you have to survive it all—rain or shine, ill health or emotional pain, you have to make it through. The other inmates, however, have no option than to simply stare into the void. And wait incessantly—for justice, for home, for freedom.

A while ago, prisoners had to serve time under the shadow of death and the pandemic. Many rumours were going around that the inmates will be released. Then the elections happened. EVM scams happened. Governments changed through the ballot box. High talk of massive reform was floated around. But the rumours of the prisoners’ release remained rumours. They float these rumours. We wait endlessly. And we keep getting disappointed. And then the same jailer, the same jail, the same inmates, the same justice system. The same (in) justice. Nothing has changed for years. Kuch to baat hain ki hasti mitati nahi hamari (There’s something in us that we don’t perish).

Is there no freedom and justice for the prisoners? Is there no equality and fraternity for them? Is the Constitution dead for the prisoners? Do the “people of India” become outsiders once they are accused of a crime? As with Dalits, Adivasis and Muslims, are prisoners also made secondary citizens?

These are the scathing questions that the prisoners languishing in the Indian prisons are asking, as they continue to proclaim themselves as ‘the people of India’. They are trying to scream through the thick prison walls and reach all of us. Can we hear the voice of these people waiting endlessly in the country’s jails, demanding justice and basic human rights?

(Views expressed are personal)

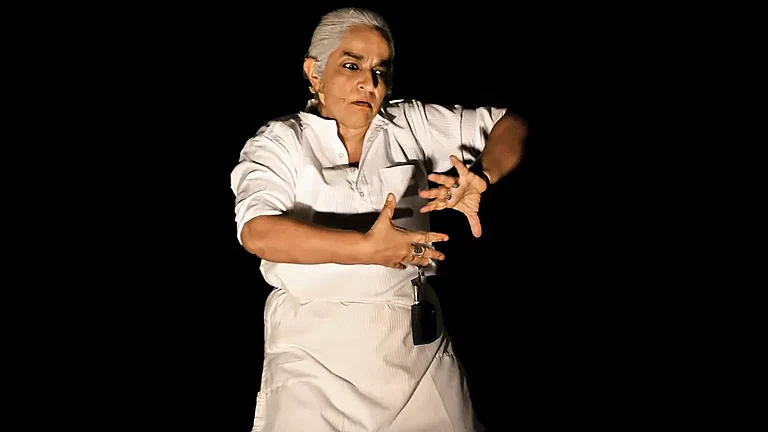

Sudhir Dhawale is an activist, poet and writer, and the editor of the bimonthly marathi magazine Vidrohi.

(This opinion piece in Marathi was translated by Anuj Deshpande and Mallika Kavadi)

This article appeared in the October 11, 2025, issue of Outlook Magazine, titled "I Have A Lot Left Inside" as 'Through The Cracks Of Prison'.

Tags