The world politics book is neither official rhetoric nor diplomatese. "It is a pretty good opening book for students of world politics, anywhere in the world," says Bajpai. Students won't read paeans to the noble Non-Aligned Movement as they would have in the old textbooks, but a more considered, critical assessment. The book has a sharp chapter on US hegemony and is blunt on US political and military failures in Iraq and its human rights record in Guantanamo Bay but does not shy away from criticism of the Soviet political system and is interestingly nuanced on globalisation. While there is no real critique of India's nuclear policy, different positions are set out on Indo-US relations "that are perhaps too complex to be managed by a single strategy", and students are encouraged to make up their own minds.

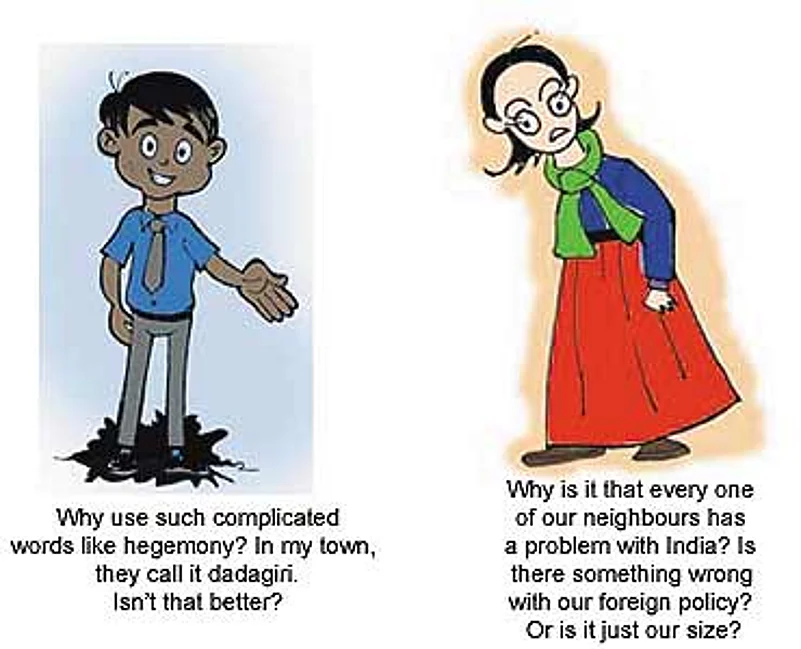

And that, really, is the biggest strength of this new crop of books. They do not force categorical judgements on students, but prod them to work out issues for themselves. There are no invitations to rote learning: facts and chronologies are hived off into boxes. The text is analytical, as are the exercises supporting it. And instead of masses of unbroken text, there's an impressive wealth of visual material: edgy cartoons, classy infographics, evocative newspaper clips and pictures (for instance, ones by Homai Vyarawalla in the Indian politics book recreate the ambience of different phases in recent history). A couple of cheeky kids, Unni and Munni, keep popping up on the margins of the text to ask inconvenient questions, like why "every one of our neighbours has a problem with India? Is there something wrong with our foreign policy? Or is it just our size?"

One that they don't ask but which needs asking, is: Teaching civics was easy, but where are the teachers to teach the new political science? Textbooks, after all, can do only part of the job.