The Air War

Short notes on the Great War

The Great War is famous for introducing tanks—first at Somme, then in great numbers at Cambrai in 1917—which replaced cavalry as the choice for mobile warfare. But it can be noted for a more sinister innovation that was to be a staple of all future wars—WW-II, Korean War, Vietnam and the wars over Iraq in our times: bombing from the air, not only of military assets, but, especially, unarmed civilian populations. As early as Jan 1915, the German zeppelins had demonstrated this with a raid on the English midlands; London and other cities were targeted next. In all, zeppelins made 40 raids in Britain, dropped 220 tonnes of bombs and killed 537 people. In 1917, German Gothas, twin-engine aircraft with potent loads, spread terror and panic. Foreshadowing the Blitz in 1940, thousands of Londoners took shelter in the Tube and night shift output dropped to 27 per cent of normal. German airpower waned along with its general enfeeblement; RAF founder Lord Trenchard took note. His mission to carry out long-range bombing of Germany bore fruit too late for this war, but the Handley Page night bombers of 1918, each capable of carrying 16 112-pound bombs and of flying for eight hours, indicated the future.

***

Subedar Bhim Singh of 6 Rajputana Rifles returned to his native place Ketu near Jodhpur in 1919, carrying an epic scar on his forehead. His grandchildren, born decades after his time on the African front in Egypt during the First World War, often wondered aloud where he got the mysterious mark. Their father, Bhim Singh’s son, also an armyman, finally told them the story. One night in 1918, the soldiers were fighting hard from their trenches, brandishing their “Vickers”, the water-cooled machine-guns of the time.

“They fought long after they ran out of water to cool the guns, which led to terrible overheating. That awful night, a bullet grazed past my grandfather’s skull, leaving a permanent mark,” says Col Jaidev Singh Rathore, retired cavalryman and Bhim’s grandson. After his return, Bhim Singh got the military decoration, IOM, Indian Order of Merit.

The Rathore clan, once destined for kingship, missed it by a hair’s breadth generations ago, but launched four successive generations into military service. They claim seven officers, born from the same grandfather or his brothers, serving and retired. Even their matches seem to have been made-in-the-military. “My wife’s family has three generations in the army. Everyone among us, given a chance, will join the forces,” says Col Rathore. His son, Aditya Rathore, is a serving colonel in the cavalry. Between them, the family has covered the two World Wars, Hyderabad and Goa’s liberation, Burma, the conflicts in 1962 and 1965 as well as 1971. Just about every border post in India has hosted a Rathore.

This is how—word of mouth rather than official records—ancestors of Indian fighters in the First World War remember their forefathers today. Some 1.7 million were scattered over all fronts the British fought, and their families still tell their stories, looking back from lives vastly altered over a century.

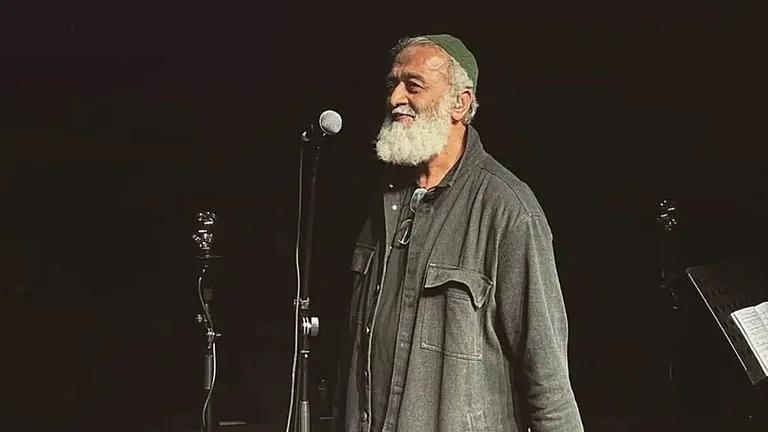

Harry Chowfin, right, was meticulous in saving army records. (Photograph by Madhupriya Choudhry)

Take Jhajjar native Lt Gen Raj Kadyan (retd), who’s settled in Gurgaon post-retirement and has lately signed up for another kind of frontline (he’s joined the Aam Aadmi Party and is their candidate from his hometown). His grandfather, Sepoy Sardar Singh of 1st Jat Regiment, was the first in the family to join the army in 1911. After travelling far and wide, to Belgium and Lille, France, and participating in both World Wars, he retired in 1939 as Jemadar holding two decorations, the Order of British India (OBI) and IOSM, equivalent to the Indian army’s VVSM. All five Kadyan brothers, as well as their grand-uncle’s clan, went the army way; and their sister married into the army.

Gen Kadyan’s wife Anita is also from a family that can trace its steps to the Second World War. Their children, Rahul and Roopali, chose civilian life. “My son is a senior vice-president in Reckitt-Benckiser in London and he will join me in my campaign this month,” says Gen Kadyan. He is convinced the country needs change, and says, “People have tried all the major parties. There’s rampant corruption and misgovernance that now needs to be genuinely fought.”

The life and work of Indians who served in the First World War is rarely more than a personal record. One unusual case is Harry Ensign Chowfin’s, whose granddaughter (from his daughter) Madhupriya Choudhry self-published a grand volume of his painstakingly-kept scrapbooks and documents last year. Madhupriya took to organising the wealth of detail he compiled through the war and into the 1960s. This includes photographs from the Great War, which Chowfin joined in 1917. “My grandfather was a record-keeper in the army, and his habit, I think, became his whole life. Every telegram, document and clipping possible, he stored. I had two trunks full of written, annotated material when I started,” she says. The Chowfins of Garhwal came from China with the East India Company to work on Uttarakhand’s fledgling tea plantations. Chowfin, disliking the disciplinarian care of his brother, and unable to resist the war-time spirit of adventure, ran off on September 17, 1917, (apparently a cloudy day) to join the 8th Lucknow division.

His ship sailed from Palamkot to Basra to Baghdad where he joined a cricket club and a theatre group. When he returned, he asked to be in the Indian army’s veterinary service, finally landing in Dera Ismail Khan, some 350 km west of Lahore. “I learned from going through the records he left that even a century later one’s work can be perfect, completely faithful to its necessary features. It was humbling to find that I, living a life of letters, had to do so little to make his book complete,” says Madhupriya, an advertising executive for 15 years now running her own agency.

Take off Subedar Karam Singh’s grand daughter-in-law, Veena, is an IAF officer

Brig J.S. Dhadwal, whose grandfather Nayak (Havildar Sahib) Tehri Ram left his village Fatehpur near Patiala for Lille, France, in 1914 and returned in 1919, has no written record of his grandfather’s service. He’s heard much about him from his own family though. Tehri Ram was one of the first commissioned into the Dogra battalion, which didn’t exist prior to 1914. Four generations later, members of the Dhadwal clan cover between them the infantry, armoured corps, cavalry and the armoured regiment.

Brig J.S. Dhadwal now lives “a pleasant retired life” in Patiala and Delhi, where his son is a serving officer, but recollects his grandfather’s tough life and post-retirement years. “Trench warfare in the First World War was terribly harsh. Soldiers witnessed limbs being chopped off, and suffered frostbite in which they lost fingers, toes, hands or feet. There were few survivors among those who fought alongside my grandfather, but when asked if he’d like to join another regiment, he refused outright. He said he’d die rather than leave the ones he’d struggled with,” he says.

Tehri Ram, who did some time in the nwfp in Bannu and then Basra, shipped to Italy and France’s trenches in a few months. He, however, picked a life pension of 8 annas a month, which inched up to Rs 14 a month in 1960, a paltry sum by any reckoning. Yet, the grandfather’s tall presence had even his great granddaughter keen to join the army in the late ’90s. She didn’t make it through though. “It’s their loss,” says Brig Dhadwal, “My daughter is in Mumbai now, married and considering an active career in law.” He feels it was the “military discipline” of those areas—Patiala, Hoshiarpur, where thousands were recruited—that keeps the men joining the army.

Bikramjit Sra is another descendant of a World War-I veteran, his great-grandfather Saudagar Singh Sra of 22nd Punjab having been in Mesopotamia. “Everything I am, I suppose, I owe to the military service of my grandfather and great-grandfather,” says Sra, 36, who lives and works in Gurgaon and trained as an engineer and MBA. He now works for niit and lives in Gurgaon with his family, whereas his grandfather, now 90, lives in Chandigarh with his father, a retired revenue service officer. “My family would still have been farming in our native village Manga Sarai, if not for the schooling my father got access to after his father’s military service,” says Sra. Sra’s father and grandfather were the first and second to graduate from their village.

Prof K.C. Yadav, who heads the Haryana Academy of History & Culture, says that though many Indians joined the war effort as soldiers, when they returned they often became agents of social change. “They were able to bring changes in outdated customs and traditions. In particular, they became advocates of women’s education,” he says.

Subedar Maj (Hon Capt) Bahorang Lal of Kurmali in western Uttar Pradesh enrolled as a Sepoy in 19 Hyderabad as a result of financial hardship. He was Subedar Major of 10 Kumaon initially, and retired in 1941, with a pension of Rs 200, which he collected at Muzaffarnagar. “My grandmother exercised strict control over this pension. She’d ask him to account for every penny because he was quite a spendthrift. A lot of it went into his favourite sweets—imarti, rabri—but he also started a school in his village, where poor students were taught free of charge,” says his grandson, Col (retd) Y.P. Singh. Bahorang Lal’s role in the First World War, though not in any of the major theatres, saw him active in anti-insurgency operations in Waziristan. It was a supportive role that had him spend over a decade in Quetta and Bannu. At the time of recruitment, several western Uttar Pradesh villages had boycotted enrolment, but Bahorang Lal persuaded a few to sign up. This, along with his role in the tribal areas of Waziristan, earned him an OBI.

The first to join the Indian army in Col Narendra Singh’s family was Subedar Karam Singh, who served in 19 Hyderabad regiment (later 19 Kumaon regiment). Karam Singh, native of a little-known village, Bhanear near Ailum, UP, served in East Africa and NWFP. “I had the misfortune of not knowing my grandfather,” says Narendra, now retired and living in Meerut. His father, Lt Col Shyam Singh, also joined the army. An extremely strict, no-nonsense man, he set exacting standards and spoke very little. “My father lost his father immediately on being commissioned and his younger brother soon after,” says Narendra. Nevertheless, the sons as well as a daughter-in-law are in the forces. The family rather cherishes their contribution over 100 years of continuous military service, which includes six who died fighting in Malaya and Singapore with the then 419 Hyderabad regiment, later famous as the 4th Battalion, Kumaon regiment. The War Memorial in Keranji, Singapore, bears the names of all six, inspiring a fourth generation to carry on with military service.

Pragya Singh is a senior special correspondent with Outlook