When we look back now, the first Linguistic Survey of India—despite gallantly aspiring to the status of a scientific project, complete with gramophone recordings—is touched with the soft, beguiling light of late 19th century Raj romance. We have an Irish ICS scholar-officer with a thing for the folk life of Bihar. Images of mule-back journeys in pine-scented Jaunsar-Bawar. And that classic tale: a team of G.A. Grierson’s language hunters on the prowl in the badlands of Punjab, looking for a variety everybody else calls ‘Jangli’ (the name a decent hint of its reputation). On reaching the approximate area, they quiz the locals. You speak Jangli? No, no, it’s not us, it’s the folks over there. At the next stop, the same routine unfolds. Not us, over there. And so it goes till the posse of linguists finds itself in the middle of the Bikaner desert!

This sense of a threshold—half incipient science, half Indian folktale—perhaps holds a clue for us. The LSI was, of course, part of the mammoth, many-pronged movement to produce colonial knowledge. It’s of a piece with identical surveys in geology, cartography, anthropology—all exciting new sciences, anchored in the purest British empiricism. Their relation with power is obvious. The unknown is a source of fear. If you know something, you begin to control it. More than the military or the law, this was at the heart of British hegemonic power. It contained a taunt—we know you, ahistorical being, better than you know yourself—that the befuddled native swallowed whole.

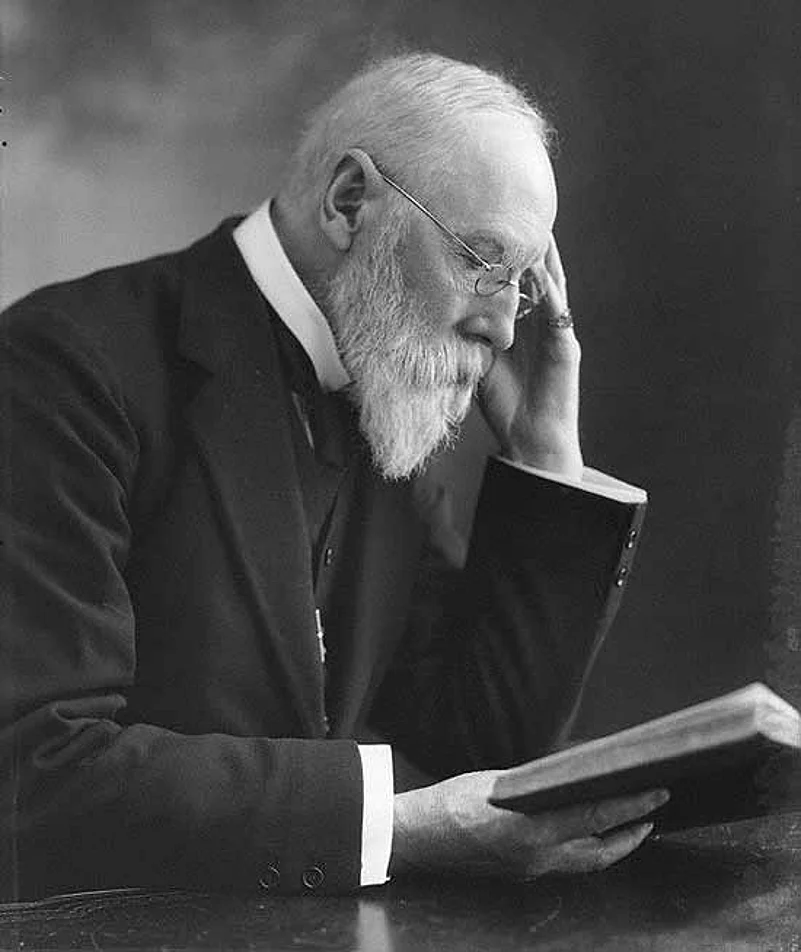

Grierson’s survey too was called a “great Imperial museum...(of the) linguistic botany of India”. The metaphor is revealing. Languages as living things; and here we had a whole bunch of specimens pinned to the book, like beetles or neem leaves, neatly annotated. As Shahid Amin reminds us, the survey and its recordings were not meant for Indian scholars, they were shipped out in their entirety to Britain, to become training material for young British civil servants.

Yet, we might find a kinship here with G.N. Devy’s PLSI. Surveys are done for a reason; they must cite a use-value for the data. All science has to justify itself. Grierson had to lobby the colonial administration for years before he could get his project going in 1898. He then spent three decades deciphering the data at his cottage in Surrey. You get a sense that he was in love with the pursuit of pure scholarship, that all this somehow exceeded the defined aim of fashioning a colonial tool. Like Jesuit scholarship leading to secular knowledge, it overflows a limit. The earliest linguistic field studies were done by missionaries, with the aim of producing Bible translations. But the science emancipated itself, became its own end. The PLSI, running into our ultra-utilitarian climate, is trying earnestly to cite some domain of ‘applied’ use. (Many exciting ones do beckon, in programming, speech technology et al.) But ultimately, no use-value is needed to justify it. What we have here is a popular atlas: it seeks to break the insular walls of science and reveal India’s linguistic richness to itself. Indians, less passionate about their own languages than erstwhile colonials, may pause a while to look at the mirror: this is who we are, how we are.

The author is deputy managing editor, Outlook; E-mail your columnist: menon AT outlookindia.com