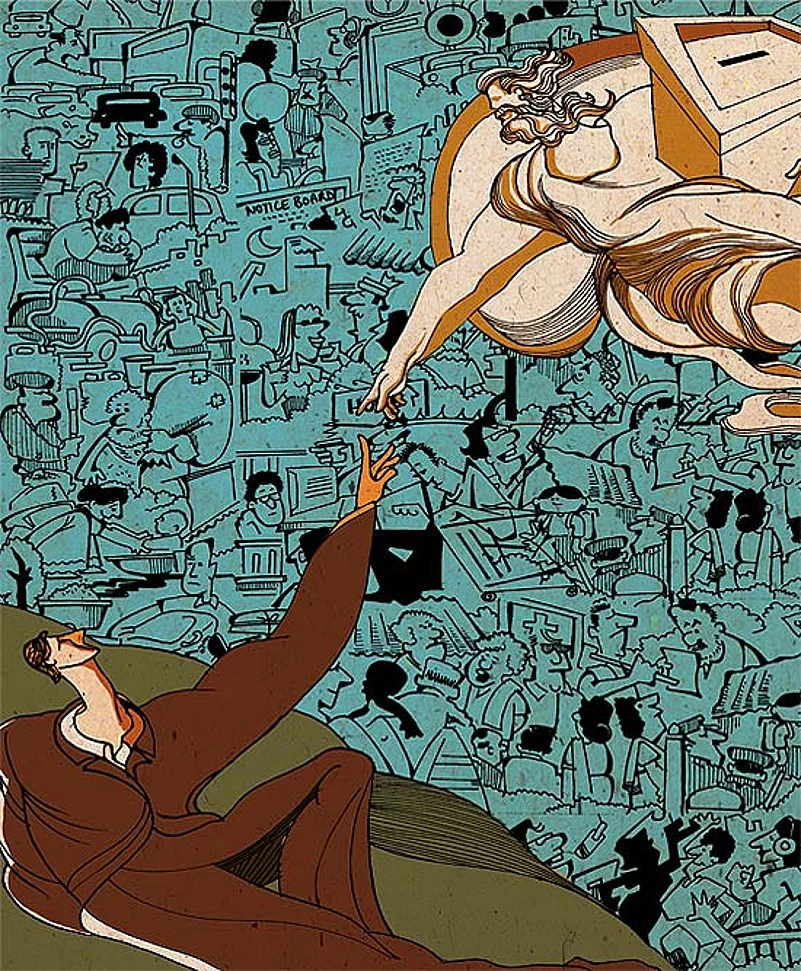

The significance of the outcome of the 2014 general election will go much beyond the obvious one: the number of seats and the vote-share parties get. Far more revealing would be the extent to which the verdict reveals the impact of trends and processes that have shaped India’s polity, economy and society for close to five decades. These haven’t received the requisite attention of the media, focused as it is, and expectedly so, on personalities and events and on issues of immediate concern and interest to voters. But these trends have figured in several works by Indian and non-Indian scholars, if only in bits and pieces.

These trends and processes have ebbed and flowed haphazardly and have their bright and dark sides. Overall, however, they have metamorphosed India into a country far removed from the one that gained independence in 1947. Their cumulative effect has been to shift the hubs of power, influence and authority away from entrenched positions towards other hubs that rarely, if ever, figured in the debates of the phalanx of distinguished men and women who framed the Constitution.

The first shift has been from the Centre to the states. Its initial intimations came from the demands for the reorganisation of states along linguistic lines in the early 1950s. But the Congress’s domination of the political system was such that few questioned its long-term impact on the federal structure. One early pointer to this impact was the election of a Communist government in Kerala in 1957 and its subsequent dismissal. But Congress hegemony received a first major jolt when it suffered defeat in several state elections in 1967. Indira Gandhi sought to contain the threat of further emasculation when she split the party in 1969. But the threat escalated. Her riposte was to impose a state of Emergency in June 1975.

This assault on the very edifice of democracy generated a backlash she hadn’t reckoned with. Her party was routed in 1977. This is when India got its first non-Congress government at the Centre. It didn’t last too long. Indira Gandhi returned triumphantly to power in 1980 and continued with her autocratic ways. Her assassination in 1984 and the massive Congress victory that followed deflected attention from the proliferation of largely caste-based parties in the states. They received a fillip after the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s report on reservations for OBCs in 1990. The formation of the first coalition government at the Centre under V.P. Singh’s stewardship bore vivid testimony to the quickening pace of the decentralisation—some would call it fragmentation—of the polity. Successive NDA and UPA governments have all functioned as coalitions. Indeed, as evidence of the changing nature of the federation, new states were carved out under their dispensation on a basis that wasn’t a purely linguistic one—in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and more recently in Andhra Pradesh. More such demands have come to the fore. No party that seeks to rule at the Centre can afford to ignore the interests—and indeed the whims and fancies—of regional leaders. That includes the dynasty-ruled Congress, which hasn’t allowed leaders from its own ranks to acquire clout.

One collateral gain from this trend is that Article 356 of the Constitution—that allows the Centre to dismiss a state government—can no longer be used summarily, the way it once was until the late 1980s. Another gain has been that national parties like the Congress and the BJP, which favoured something akin to a unitary state, will perforce have to be attentive to the demands made by the states. These include a more equitable transfer of resources, measures like tax rebates, grants of subsidised loans, loan waivers, grant of special status etc.

New Centre-state coordination mechanisms would also need to be put in place to counter terrorism, which respects neither the borders of states nor the borders of neighbouring countries and to nip in the bud forces of regional chauvinism that seek to intimidate ‘outsiders’ or forces that resort to violence in the name of religion. Efforts would have to be made to ensure that regional parties do not interfere in the conduct of foreign policy vis-a-vis the neighbours or vis-a-vis countries with substantial populations of Indian origin.

Back story Indira Gandhi was decisive, even peremptory. (Photograph by Magnum, From Outlook 28 April 2014)

Overall, therefore, a push for greater federalism is on the cards. However, this trend has a flip side to it: most regional parties are family fiefdoms or under the sway of a single individual. There is as yet no sign that they are prepared to let go of their stranglehold. But all are agreed that things won’t fall apart and that the Centre will continue to hold only if it pays more heed to the interests of the states.

The second shift is from the state to the market. For more than 30 years after independence statist intervention in the economy was the order of the day. It was the motor of development. The goal was self-sufficiency. The private sector had its place in this licence-permit raj—but a decidedly secondary one. It was the public sector that was allowed to flourish. The picture began to change after Indira Gandhi’s return to power in 1980. The steps she took to liberalise the economy were tiny and hesitant. They picked up pace during the Rajiv Gandhi era. But the paradigm shift happened under P.V. Narasimha Rao’s watch in 1991. A World Bank expert hailed it as the most significant event after the implosion of the Soviet empire and China’s embrace of the market economy. Atal Behari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh hastened the process.

Global integration and domestic deregulation accounted for the economy’s spectacular growth. (It did slow down in the UPA’s second term in power.) But the reforms had their share of critics who railed against India’s ‘meek submission’ to international financial institutions and multinational corporations. The reforms, they further charged, had widened social and regional disparities, encouraged the growth of crony capitalism, generated scams and devastated the environment. Reforms didn’t create jobs in adequate numbers or contain inflation either.

Partly to address such criticism and partly to improve their electoral prospects, the UPA initiated a slew of social welfare measures targeting the poor and marginal sections of society. These have also been criticised on the grounds of faulty implementation and the intolerable pressures they bring to bear on the public exchequer. However, governments in future won’t dispense with these measures altogether. Nor will critics be able to stem the tide of reforms. The state’s control of the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy is bound to loosen further to the advantage of corporate India—not least because aspirational Indians, even from the SCs, STs and obcs, repose much greater trust in jobs than in freebies and entitlements.

The third shift is from government to civil society. Thanks to the extensive coverage it has received in the media, the latter, spearheaded by the middle classes, has made its voice heard on a host of issues: violence against women, children and minorities, political and bureaucratic corruption, protection of the environment and of the rights of communities whose lands are exploited for their forest and mineral wealth, misuse of powers by the police and the armed forces, providing relief and rehabilitation to victims of natural or man-made disasters, catering to the needs of slum dwellers and senior citizens, punishment for those who exploit superstition and blind faith for personal gain and so forth. Never before have so many young people, who were chastised for their lack of interest in public affairs, taken to the streets in such large numbers to compel the government to pass laws or take strident action against the wanton abuse of citizens’ rights.

The enthusiasm initially generated by the Anna Hazare movement and by the early success of the fledgling Aam Aadmi Party indeed testifies to a new phenomenon in public life. Protests are no longer confined to seeking quotas and entitlements. They are for better civic services, safeguarding the security of women and, above all, for effective, transparent and accountable governance.

However, the swift disenchantment with the phenomenon also calls for introspection. One reason for it surely is the propensity of the protest movements to reduce complex issues to a single point—corruption. Another is to make wild and unsubstantiated allegations against prominent politicians, business leaders and bureaucrats. Yet another is to rail against all established institutions—from Parliament to courts and several government-appointed bodies.

All of this came to be seen as the misuse of an otherwise powerful weapon that citizens are entitled to wield: the Right to Information Act. But that can in no way detract from the fact that civil society now has the wherewithal to muster public opinion against or in favour of a particular cause of concern or interest to it. Such pressure from ‘below’ for transparent and accountable governance has added a vibrant dimension to Indian democracy. It will continue to keep the nation’s movers and shakers on tenterhooks.

First push JP galvanised political change in the 1970s. (Photograph by HT)

The fourth shift is from an upper-caste-dominated political and economic system to one where those on the lower rungs of the social ladder play a more and more prominent role. The process began barely two decades after Independence, in southern and western India, where the struggle for social equality has a long history. It gained salience in the rest of the country during the Jayaprakash Narayan-led movement against Indira Gandhi’s regime. And it gathered steam with the implementation of the recommendations of the Mandal Commission report.

Along the way, the so-called intermediate castes, who gained the most from land reforms, swiftly managed to acquire political power and, by and by, to control the bureaucracy and the police. They then began to accumulate economic clout as well. Marathas in Maharashtra, Jats in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, Lodhs in Madhya Pradesh, Reddys and Kammas in Andhra Pradesh, Vokkaligas in Karnataka, Vellalas in Tamil Nadu and Yadavs in the three populous states of the North. But they have had to give way to those just below them.

The trajectory of the initial beneficiaries of the system of reservations—SCs and STs—has been along the same lines though the pace of their progression has been distinctly slower. Overall, however, India’s age-old caste system has undergone a thorough overhaul. The more egalitarian caste composition of elected bodies reflects the change of this peaceful social revolution. So does, increasingly, the presence of the lower castes in other fields of public endeavour such as business and the professions.

This is not to argue that caste-based identity is a thing of the past. It still matters in elections. But the exploitation of the sense of victimhood has begun to fetch diminishing returns. The Muslim minority is an exception to this trend. But even this minority (especially its educated and urbanised sections) has started to question those parties that have sought its votes without bothering to seriously address its bread-and-butter issues. To that extent, the growing presence of the lower castes in the power structure through the reservations system or on the strength of meritocracy has also brought about a sea-change in the functioning of Indian democracy.

The fifth shift is from a geriatric India to one where an overwhelming proportion of the population is below the age of 35. It is most evident in the corporate world and in politics, though the young are making their presence felt in just about every other domain of activity. None can afford to ignore them. That should be obvious from parties’ manifestos for the 2014 elections.

However, given the numbers of young people, the system is faced with a humongous challenge. It needs to provide them with quality education and vocational skills. And it needs to ensure that they get the security of gainful employment. Unless this challenge is confronted in right earnest, the demographic dividend could swiftly lead to a demographic liability. That could destabilise society and the democratic order in ways best not imagined. Either way the young will continue to change India as never before for at least another three decades.

Less obvious, but by no means less significant, is the sixth shift—from a male-centric India to one that is more gender-balanced. Even as atrocities against women continue to grow, there is a greater awareness today than at any time in the nation’s history of their rights to security, education, health and jobs. And while no end is yet in sight to the ‘moral policing’ or to the variations of ‘khap justice’, there is no gainsaying the fact that women are increasingly breaking the glass ceilings that have kept them confined to the kitchen and the marital bed. And this even without the much-promised reservations in Parliament and legislatures.

Their involvement at every echelon of the political, economic, social and cultural power structures is ushering in another quiet revolution. It threatens the culturally-shaped privileges and prerogatives of the Indian male as never before. And that is all to the good. Despite setbacks, the quest for gender parity is all set to accelerate.

New movement Crowds heading for Anna Hazare’s famous protest at Ramlila Maidan, Delhi. (Photograph by PTI)

Two other shifts merit attention. They relate to mindsets and attitudes. The first one (highlighted time and again by the distinguished scientist R.A. Mashelkar) is a move away from ‘techno-nationalism’—which was inevitable during the long period when India was denied access to critical technologies—to ‘techno-globalism’. It is driven by robust global knowledge and innovation hubs that are intrinsically linked to the globalisation of the economy. Transnational companies turn to them to create goods and provide services across several geographies.

But ‘techno-globalism’ also addresses challenges ranging from climate change to the water crisis. Indian engineers, scientists and managers are at the forefront of this trend though the country has a long way to go before it emerges as a global innovation hub. Budgetary allocations for research and development are niggardly. Political interference and bureaucratic wrangling stymie innovation. But given the burgeoning national mood in favour of a rapidly growing and competitive economy, ‘techno-globalism’ is poised to take a great leap forward.

The other shift, a corollary of the one mentioned above, is from an inward-looking India to one that is more and more outward-looking, thanks to satellite television, the internet and travel and/or stay abroad for education, jobs or tourism. The exposure to the outside world has had considerable impact on lifestyles but also made Indians more aware of the elements that should constitute their cultural and national identities.

In the former instance, shades of saffron have surfaced across large swathes of the country. And in the latter instance, there is a heightened concern with the growth of cross-border terrorism rooted in religious extremism. Across the board, however, there is an eager willingness to reach out to the outside world to develop the economy and guarantee the nation’s security. Nowhere is this shift been more pronounced than in the conduct of India’s foreign policy. Though it has witnessed several avoidable ups and downs—due largely to a lack of an invigorating vision and an energetic leadership—it has managed to cope with the challenges of the post-Cold War world. The move away from a moralising, ideologically-driven non-alignment to an unsentimental, pragmatic multi-alignment that keeps a sharp focus on interests of critical importance to the country’s economic growth and military prowess is here to stay.

What these trends and processes suggest is that the binary of ‘India Shining-India Whining’ that has shaped public discourse for the past decade limits one’s understanding of the profound transformations in the country since its independence. They could perhaps even herald the advent of another republic in all but name, a republic that would be different in spirit and temper from the one that the people of India gave themselves on January 26, 1950.

The preamble of the Constitution mentions ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ as the republic’s distinguishing features. The first has been reduced to a simulacrum. The second has received a battering under all governments. But be grateful for small mercies. Our republic is also democratic. That alone will allow us to make a bonfire of the hubris, conceits and vanities of the nation’s lords and masters.

The writer is a consulting editor with the Times of India and a member of the editorial board of The World Post