Points Of Departure

- Varun Gandhi has vowed not to badmouth his aunt Sonia, or cousins Rahul and Priyanka

- He was quoted as saying Modi’s rally in Calcutta in 2014 drew fewer people than claimed

- He has taken an ideological U-turn since his Hindutva-laden “hate speeches”

***

When Feroze Varun Gandhi wrote a congratulatory note to each of the 1,07,452 village pradhans elected in Uttar Pradesh in January this year, it didn’t come as a surprise. Son of Sanjay Gandhi, the BJP MP from Sultanpur had been barnstorming the state for some time, holding farmer-outreach programmes among other exercises, with an eye on the main chance. And his followers had created a social media campaign promoting the idea of projecting the party’s “most popular face” in UP as its CM candidate.

Various surveys too—conducted for ETV, India Today, Amar Ujala and ABP by different agencies—put him ahead of Rajnath Singh, Kalyan Singh and Yogi Adityanath, with Smriti Irani, apparently fancied by the Sangh parivar, way behind. But they may have been far too eager and the aggressive campaign put off the other contenders. And when his supporters plastered Allahabad last week with his posters to the exclusion of other state leaders, they cried foul.

It was an act of indiscipline, conceded state BJP chief Keshav Prasad Maurya. Eighteen party workers were admonished for launching the campaign and, in a one-on-one meeting, Narendra Modi is said to have told the 35-year-old to cool down. At the PM’s rally in Allahabad, Varun was not given a place on the dais. While Anupriya Patel, MP and ally, sat bang behind Modi, Varun only got a seat at the back. When he gave a miss to party chief Amit Shah’s dinner and meeting with MPs from the state that evening, it became clear that the MP may have shot himself in the foot, but not without showing the party elders that he could play the game.

Some say his decline in the party has not been sudden, though. In 2014, he was stripped of his position as general secretary and the party grapevine was quick to catch on that Modi and Shah had no soft corner for him, given their hatred for the Gandhi surname. He was seen as too independent, too cocky and too stubborn to their liking. He had pointedly drifted away from hardline Hindutva, consistently refused to badmouth his aunt Sonia Gandhi and cousin Rahul, and barely invoked Modi’s name in his own campaign.

‘Varun for CM’ campaign stepped on too many toes

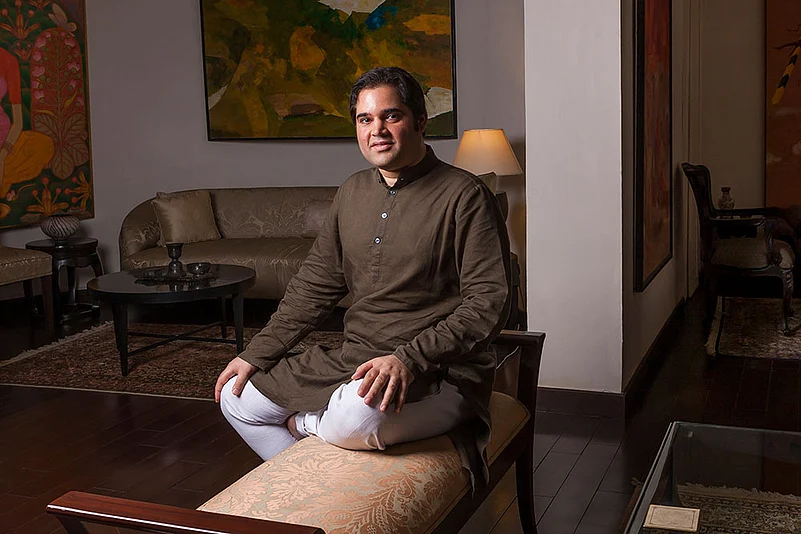

When Outlook catches up with Varun Gandhi on his return from the Allahabad national executive, he does not betray any restlessness. In his spacious living room with sunlight seeping in through the green foliage outside the huge glass windows of his plush Jorbagh residence, he is in a reflective mood. At the mention of next year’s assembly election and his probable role in it, he quips, “My family has always been part of national politics.”

Reflecting on 12 eventful years in politics, he admits having followed a steep learning curve. Possibly he took the plunge 10 years too early, he feels in retrospect. But there is no regret. It hasn’t been easy. It took a while, and some doing, to start feeling comfortable in his skin. He is conscious of his lineage, but that is not part of his day-to-day dialogue. His politics is a reflection of a quest unto self: “I feel now I am the man I want to be, but it is a continuous process.”

Politics is in his blood. He was elected to lead in school and college—one of the first brown men at the London School of Economics to have done that. He went on to hold senior positions in the BJP before Amit Shah became the president. As one of youngest ever general secretaries—a stint for three years until 2014—he was in-charge of West Bengal and the Northeast.

His evolution as a politician also had its share of controversies. He was accused of inciting communal passion at a rally in 2009 and was jailed. The court exonerated him of all charges due to lack of evidence. He is sensitive about this issue but doesn’t shy away from the question. There was no question of antagonising any community, he says, recalling that his mother, Maneka Gandhi, now a minister at the Centre, had won four elections from Pilibhit against the BJP. He claims to have worked extensively in no less than 300 Muslim-dominated villages there.

In times when bad news spreads like wildfire and good work is almost never part of the political discourse, Varun claims to have introduced in his constituency several innovative schemes. He roped in specialists from Belgium to teach lace-making to 4,000-odd Muslim families—a vocation that supports 25,000 families now. Then, with the help of scientists from Punjab Agriculture University and Pusa Institute in Delhi, he introduced the cultivation of exotic vegetables such as iceberg lettuce, cherry tomatoes and broccoli in Pilibhit.

He also diverted a part of the inheritance bequeathed by his maternal grandmother in 2011 to create a cold-supply-chain to ensure exotic vegetables from Pilibhit are sold in the markets of the capital. His dream project is to involve local elites to support pauperised and debt-ridden farmers in UP, who are on the verge of committing suicide. The initiative has great promise and has shown initial success. He talks about his trysts with politics and his projects with the zeal of an activist.

An early riser, he spends an hour every morning reading before his wife Yamini and two-year-old daughter, Anasuyaa, wake up. One of the better-read politicians, his interests range from philosophy and science to fiction; particularly, the works of existentialist writers like Marcel Proust and Albert Camus. His collection of books is enviable as also his collection of artwork from all over the world. In an earlier interview, he had confided he had 2,000 paintings in his farmhouse, many of them by contemporary masters. Lately, he has developed a liking for short stories—Canadian noble laureate Alice Munro is his current favourite. He likes watching TV (favourite serials include Damages, Office and True Detective). Unlike many other politicians, he confesses to being home-bound, and admits to hanging out only with select friends. “I married my best friend and am very close to my mother,” he adds.

His idea of relaxation is writing poems. “I will write poetry till the last day of my life,” he says as his face lights up with a smile. “It is not just cathartic, it is enthralling.” He is also a columnist writing on a range of subjects (he has written several pieces for Outlook). Methodical, he says he spends six days researching on topics he wants to write about while doing the actual writing over the weekend.

His enquiry ranges from issues around micro-finance to the rising influence of the Left in the West. An autodidact, his writings, often translated in various regional languages, are neither fault-finding endeavours nor polemic in nature. They bear an academic tone and discuss issues threadbare. His ideological leaning, as revealed by his writings, is left of centre—something he doesn’t contest. That’s fairly different from the ideology of the party he represents.

He remains individualistic in a party that values conformity. He does look like the odd man out as the BJP struggles with how to deal with him. Possibly the party’s best bet in UP to take on Akhilesh Yadav and Mayawati, his distance from the RSS and the local party organisation make the decision quite complicated. While he seems poised on a precipice, in danger of being sidelined if not expelled, the party too appears undecided.