It was an experience that scarred his childhood. In August 1947, eight-year-old Ali witnessed the massacre of his entire village in Ludhiana district, including his family, by a mob mad with bloodlust. The victims were rounded up in a courtyard. Ali found the nerve to make a sudden run. But he bumped right into the knees of one of the attacking gunmen. Unexpectedly, he grabbed Ali and gently led him away.

This is one among many anecdotes that Guneeta Singh Bhalla, the Indian-American founder of The 1947 Partition Archive, has digitally stored for posterity. The ‘citizen historians’, as she calls herself and her team of 500 people from 20 countries, have collected 1,200 testaments since 2011. To collect stories from across the globe, the team uses crowd-sourcing, teaching people how to conduct oral history interviews via online seminars. They believe spreading empathy through these conversations is crucial to conflict resolution.

Guneeta grew up listening to Partition stories from her grandparents, who fled west Punjab in 1947. When she moved to the US in middle school, Bhalla wondered why what her grandmother termed “an apocalypse” didn’t even merit a mention in history classes alongside important world events. “In the US, it was not even mentioned in textbooks as we learned about the Holocaust and Hiroshima/Nagasaki. That bothered me, because the sentiment contrasted sharply with the stories I had heard.”

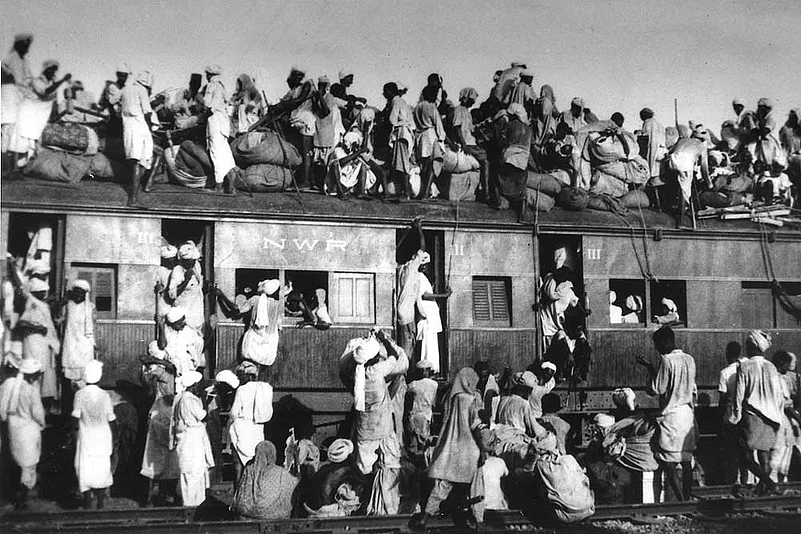

That spurred Bhalla to juxtapose first-hand oral accounts of Partition with the period’s history, to enliven the past with lived rawness. “No one was talking about the largest mass human displacement in history that rendered 15 million homeless—a population larger than some West European nations combined.”

Guneeta stumbled upon and felt the intense impact of oral narratives during a research trip to Japan, when she visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, built to commemorate victims of the atomic bomb. There, she came across the elaborate oral archives. “It was powerful, hearing stories of experiencing the atomic bomb from survivors. Suddenly, it was very real and human and I felt their pain much more than during watching videos of the mushroom cloud or reading written accounts.... I knew the same had to be done for Partition.”

Every story was an eye-opener in its own way, in that it challenged the global perception of South Asian culture, especially those concerning women and children. Guneeta recalls interviewing 93-year-old Bhim Sharma in Batala, who spoke vividly about the day his village, Narowal in west Punjab, was surrounded. Everyone was holed up in one house. Then, when hope was nearly lost, came three women riding on horseback from behind a hill. Masked as men, wearing turbans on their heads and belts of ammunition across their bodies, they caught the attackers unawares and lobbed grenades at the leader, killing him. The crowd melted away. Months later, and thousands of miles away in Morgan Hill, California, Kuldip Kaur from the same village corroborated Sharma’s story. She recalled later that the women on horseback had also turned up to defend a caravan she was stuck in.

Guneeta cherishes the rewarding connections formed with elders whose stories she recorded. She laments the minimal interactions between youngsters and the older generations in modern times, as “this is how knowledge was passed down through generations, through learning from the experiences and life stories of our elders”. Remarkably, some elders, their numbers diminishing with every passing year, were talking of their searing stories for the first time.

This makes Guneeta’s endeavour a challenge in itself, “a race against time, since more witnesses are lost every day”. With the goal to collect 10,000 stories by 2017, The Partition Archive wants to preserve bits of lived reality before they are lost to us forever.