Shyna was arrested on charges of forging documents to procure SIM cards, allegedly harbouring Maoist leaders from Andhra Pradesh and conspiring to attack outlets of multinational companies.

In cases like Shyna’s, the punishment does not end at the prison gates. Bail becomes another point of control, regulating movement, disrupting medical care and fracturing social relations.

According to Anoop Mathew, a coordinator working on the rights of political prisoners, incarceration under the UAPA often comes with conditions that border on the extra-legal.

The Sting Of The Bar

India today has more than 4.3 lakh undertrial prisoners. A significant number of them are linked to political cases

Advocate P. A. Shyna consulted a gynaecologist after falling unwell, nearly a year after she was released on bail in cases registered under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Bail, however, did not translate to freedom. One bail condition required her to travel to Coimbatore twice a week to appear before investigating officers, even as she quietly went about her life plagued by surveillance and fatigue.

The doctor examined her, prescribed medication and advised complete rest. For Shyna, rest was neither simple nor feasible. Any departure from bail conditions required court approval, and even a brief exemption from travel needed a medical certificate, turning a routine consultation into a legal exercise. When she explained this to the doctor, a question followed: why was a certificate required? Shyna spoke of the cases against her and her bail under the UAPA. The shift was immediate. The soft-spoken doctor turned cold, withdrew the prescription and asked her to leave the consulting room.

“I was dejected,” Shyna recalls. “How could a doctor behave like that? Doctors are meant to be lifesavers. They are expected to treat every patient with empathy.” Yet, for her, the episode was not an aberration. It was emblematic of a deeper malaise. “The doctor was only a representative of a society in which the police systematically intrude into the lives of activists, even after they are released on bail,” she says.

That intrusion has been relentless. Shyna was forced to move from Ernakulam to Thrissur after repeated police visits to her residence. House owners were questioned, warned and subtly intimidated about the ‘risks’ of sheltering a UAPA accused. The message was clear: association itself was suspect.

In cases like Shyna’s, the punishment does not end at the prison gates. Bail becomes another point of control, regulating movement, disrupting medical care and fracturing social relations. Even spaces traditionally associated with care and neutrality, such as a doctor’s clinic or a rented home, are not insulated from the stigma attached to national security laws.

Shyna was arrested on charges of forging documents to procure SIM cards, allegedly harbouring Maoist leaders from Andhra Pradesh and conspiring to attack outlets of multinational companies. The police also accused her of spreading Maoist ideology.

Once a prisoner, always a suspect. Whether on bail or even after acquittal, many former undertrials recount stories of continuous harassment, of jail manuals being disregarded, of dignity routinely violated and of an unrelenting surveillance that follows them beyond the prison walls.

The experience of D. Dinesh, a dentist from Coimbatore, captures this afterlife of incarceration. Arrested from his own dispensary, he was later granted bail. But release did not mean return. One of the bail conditions required him to stay in Kochi, a city with which he had no prior ties. More than a year after his release, Dinesh continues to live in Kochi, displaced from his home and profession. “I can’t take up any work here,” he says. “My practice, my patients, my entire life are in Coimbatore.” Despite being out on bail, he feels constantly watched. “The police are still after me. They follow me and keep track of who I speak to.”

For Dinesh, bail has become a hollow legal formality. The restrictions imposed by the court, compounded by everyday policing, have made it impossible for him to resume a normal life. “What is the meaning of bail,” he asks, “if you are still treated like a prisoner outside prison?”

His story echoes a larger pattern, where freedom is conditional, movement is monitored and suspicion becomes permanent. In such cases, the criminal justice system extends its reach far beyond confinement, transforming bail into a prolonged, informal punishment. “I have been involved in various political and social activities in Coimbatore. I became a doctor to serve the needy. The charge against me is that my photo was reportedly found in the electronic device of a Maoist activist who was killed in an encounter in Kerala. The trial is going on. I am not sure whether I will be acquitted. They have denied the right to profession,” he adds. Dinesh was arrested on allegations that he had participated in a Maoist meeting purportedly held in Kerala’s Malappuram district. He was booked under Sections 25(1)(b) and (c) of the Arms Act, along with Sections 20 and 38 of the UAPA, which deal with membership and association with a banned organisation.

The UAPA belongs to a lineage of draconian security laws, including the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) and the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA). Though framed as temporary responses to extraordinary threats, these laws became synonymous with abuse. After POTA’s repeal, successive governments expanded the UAPA, tightening bail and widening its scope. Despite stated opposition, political parties across the spectrum have continued to invoke it, revealing its enduring political utility. In this sense, the UAPA is not merely a legal statute; it is the inheritor of a political tradition in which extraordinary laws, once normalised, outlive the crises that produced them.

Allan Shohaib and Thwaha Fasal were students when they were picked up by the Kerala Police and booked under the UAPA. Their arrest triggered a wave of protests and public outrage. At the time, both were members of the CPI(M). Yet the state government, and later the party itself, stood by the decision to invoke the UAPA, alleging that the two were Maoist sympathisers. For Allan and Thwaha, the charges marked a decisive rupture in their lives. “I was a CPI(M) branch member then. I still don’t know why I was arrested,” Thwaha says. The accusation, he insists, came without explanation, only the weight of a law that renders defence secondary to suspicion.

Allan, a law graduate, has spoken publicly about the quiet but relentless surveillance that followed his release on bail. In a social media post, he described how police monitoring repeatedly disrupted his attempts to find housing. “Whenever I rent a place to stay, police visits put the landlord under pressure,” he wrote. “Eventually, I am forced to move.”

Their experiences are not isolated. Over the past decade, eight alleged Maoist activists have been killed in police encounters in Kerala. Around 20 people are currently lodged in the state’s prisons under the UAPA for their alleged links to Maoist organisations.

Whether on bail or even after acquittal, many former undertrials recount stories of continuous harassment.

According to Anoop Mathew, a coordinator working on the rights of political prisoners, incarceration under the UAPA often comes with conditions that border on the extra-legal. “Lawlessness and arbitrariness have become routine in many prisons,” he says, pointing in particular to the high-security prison at Viyyur. “The rules exist on paper, but in practice, officers exercise unchecked power.” Anoop spent nearly a decade in prison under the UAPA in connection with alleged Maoist cases. Detained in the Coimbatore Central Prison, he describes incarceration not merely as confinement but as a systematic stripping of personhood. “I am a political activist,” he says. “When a person is brought to jail, the first thing the authorities do is search his body, after making him completely naked. This century-old practice is meant to convey one thing: that you are no longer an individual with rights but a body assigned a number.”

Anoop says he repeatedly resisted what he describes as extra-legal practices adopted by prison authorities. Advocate Shyna corroborates his account. “I was subjected to body searches in public,” she says. “Only after we resisted several times were they forced to conduct it inside a room.” Anoop points to what he calls institutionalised illegality inside Kerala’s prisons, particularly the high-security jail at Viyyur. “The authorities frequently issue administrative orders to bypass jail rules,” he says. “Jails are meant to be correctional homes. They no longer function as such.”

Civil society groups were compelled to intervene after serious allegations of custodial torture emerged from the Viyyur high-security prison. Subsequently, a National Investigation Agency (NIA) court pulled up jail authorities for adopting illegal measures, lending judicial weight to long-standing complaints by prisoners and rights groups.

Rajeevan T. K, who spent nearly five years in prison on charges of alleged Maoist links, speaks of everyday deprivations that rarely make headlines. “Denial of books and restrictions on interviews are common,” he says. Even basic entitlements, such as prison wages, are routinely withheld. “Authorities set unachievable work targets, and when those are not met, wages are denied. The same officials who are supposed to uphold the rule of law are the ones violating it.”

Now out on bail, Rajeevan is still unable to return home. A bail condition prevents him from going back to Wayanad, forcing him to stay in Kochi under constant police surveillance. “The house owner is under tremendous pressure from the police,” he says. “This is the reality of life after prison for an undertrial under the UAPA.”

These accounts reveal a disturbing continuum, from arrest to incarceration, from bail to life outside, where the presumption of guilt endures long after court orders grant formal liberty. Publicly, political parties across the ideological spectrum present themselves as champions of human rights and democratic values. In practice, former prisoners argue, they often adopt expedient methods to stifle dissent.

Vivekandan, who spent nearly 10 years in jail across multiple UAPA cases, says repression has remained consistent regardless of the party in power. “I was arrested during both the AIADMK and the DMK regimes,” he says. “The last time was for organising protests against polluting industries like Sterlite in Thoothukudi, and for my involvement in various human rights issues.” Associated with revolutionary movements since his college days, Vivekandan rejects the allegations levelled against him. “In a democracy, people have the right to express political opinions and fight for them,” he says. “Without an iota of evidence, the police claimed I had conducted arms training.” Now on bail and living in Chennai, he remains under surveillance. “Because of intimidation and monitoring, I am forced to keep shifting houses,” he says. “The prison may be behind me, but the punishment is not.”

Kerala-based independent journalist Rejaz M. Sheeba Sydeek was arrested by the Maharashtra Police in May last year over a social media post related to “Operation Sindoor”. He has remained in custody since. In Kerala, meanwhile, Rejaz was also booked in connection with a pro-Palestine rally. “When he was produced before a Kerala court in the Palestine rally case, his parents were not even allowed to meet him,” says advocate Thusar Nirmal Sarathy, pointing to what he describes as the routine erosion of basic procedural dignity.

The shrinking space for expression is evident not only in arrests but also in the state’s approach to cultural production. The Kerala government’s refusal to grant permission to publish a novel authored by Roopesh, who is in prison under the UAPA for alleged Maoist links, has drawn widespread criticism. Several writers and cultural figures aligned with the mainstream Left have publicly urged the government to allow the publication, arguing that incarceration cannot extinguish creative expression. The Pinarayi Vijayan government, however, has remained unmoved.

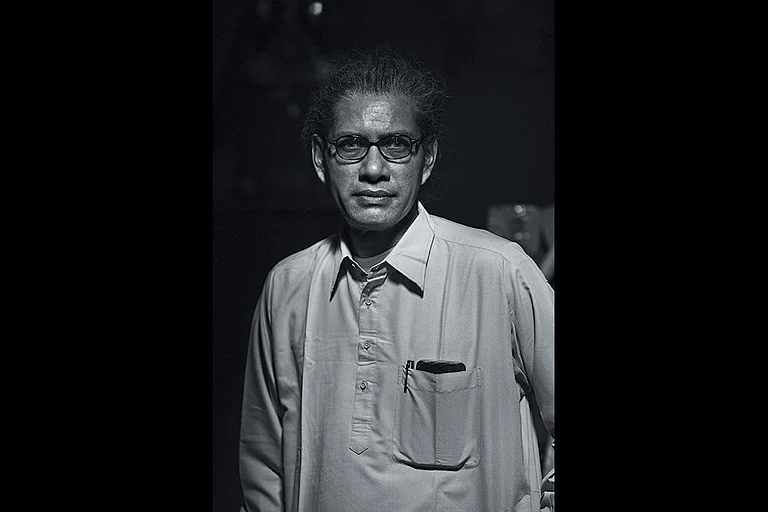

Roopesh was arrested in Coimbatore in 2015 along with his partner, advocate Shyna, and is currently lodged in a central prison in Kerala. Speaking through Shyna, Roopesh situates his experience within a broader political trajectory, arguing that laws enacted as exceptions are steadily being normalised.

For Roopesh, the danger lies not only in the UAPA itself but in how its logic is spreading. “Several provisions that were once considered exceptional under the UAPA are now visible in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita as well. This is the normalisation of what was earlier justified as extraordinary,” he says.

India today has more than 4.3 lakh undertrial prisoners, nearly three-fourths of the total prison population, according to the Prison Statistics Report 2022. A significant number of these incarcerations are linked to political cases, where arrest itself becomes a form of punishment. In this context, the Supreme Court’s recent shift, holding that prolonged incarceration and delays in trial cannot by themselves be treated as a decisive ground for granting bail, carries profound consequences.

N.K. Bhoopesh is an assistant editor, reporting on South India with a focus on politics, developmental challenges, and stories rooted in social justice