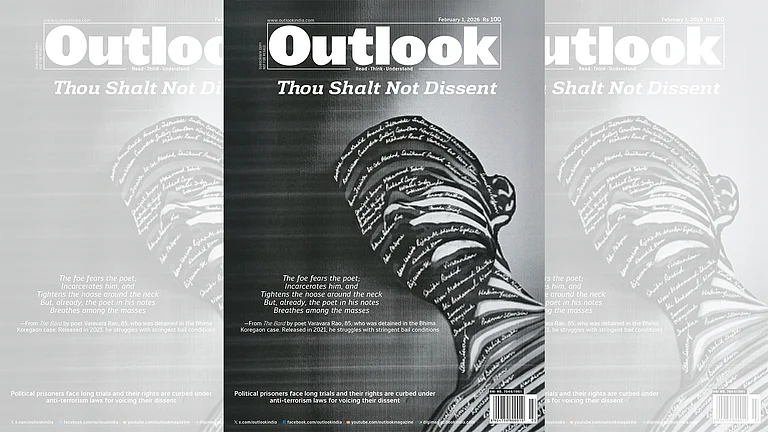

Varavara Rao was released on medical bail in August 2022, but he continues to live in Mumbai due to stringent bail conditions

He is not allowed to go to Hyderabad for his medical treatments, his literary activities are curbed and he isn’t able to meet his family in Telangana

He struggled to find an apartment in Mumbai as he was held under UAPA. Because of this, his wife is not able to live with him in the city

Voices From Prison: Alienating A Poet From A Language He Deeply Loves Is Painful, Writes Varavara Rao's Daughter

The poet and activist was jailed in connection with caste violence that erupted in 2018 in Bhima Koregaon. He was 78 then. Though he was released on medical grounds in 2022, he is still confined to Mumbai. In this first-person account, his daughter Pavana writes about how multiple incarcerations could not break her father’s strength and soul

My father Varavara Rao was arrested in the Bhima Koregaon case in 2018 under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). He was 78 then. He was released on medical bail in August 2022, but he has to stay in Mumbai, living like an exile, due to his bail conditions. He is not allowed to meet his co-accused, there is no one to talk to him in Telugu, he is not allowed to go to Hyderabad for his medical treatments, his literary activities are curbed and he isn’t able to meet his loved ones in Telangana.

This wasn’t his first arrest; he has been arrested many times in the past, even in 1973, before the Emergency, for his political activism. I was a newborn baby (hardly a month old), when Bapu was arrested. Since my childhood, I have been seeing him getting arrested as a political prisoner. My mother Hemalatha used to visit him in jail.

He was mostly lodged in jails in Andhra Pradesh. There used to be a Class-B category for political prisoners. Authorities used to provide them with facilities like a cot and a table and chair set inside the prison. During his incarceration in Maharashtra, it was the first time he was denied such facilities. We had to write petitions to the court seeking permission to provide him with even the most basic things. All petitions would end up in long-drawn legal battles.

When a person is incarcerated hundreds of kilometres away, writing letters is the only means of communication. The prison authorities wouldn’t allow him to write in Telugu. They would insist that we write in Hindi or English because they wanted to read those letters. My father has been a Telugu writer and a poet. Alienating him from writing in a language he deeply loves was painful.

I remember, when he was in Yeravda jail in Pune, providing one blanket to him was a task. We had to move an application to the court and wait for permission. For most of his life, he has lived in a dry state like Telangana. Pune winters were too harsh for him. His health deteriorated in prison. The pandemic was a nightmare. He was diagnosed with COVID thrice.

After his last COVID treatment, he was transferred to Taloja Jail in new Bombay. My mother and I visited him in the hospital. His condition broke us. We felt as if we were seeing him alive for the last time and he wouldn’t survive. But he is a fighter. His sheer will power and people’s love and wishes saved him. He slowly recovered.

Bapu comes from a humble family. He was born in 1940 in Chinna Pendyala village in Warangal district, in present-day Telangana. He grew up in a politically aware family, which played a crucial role in his intellectual and ideological development. His early exposure to books, debate and progressive literature shaped him as a poet, professor and a political activist.

My elder uncles were also arrested during India’s freedom struggle. He has a lineage of political activism. Fighting for human rights and the poor stemmed from Bapu's own experiences of poverty. It was always a hand-to-mouth situation in his family; he used to walk kilometres some times to attend college.

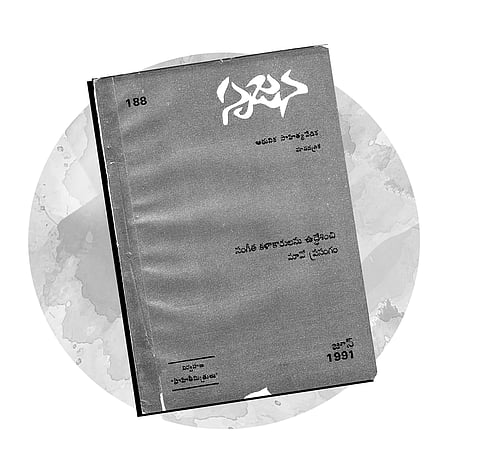

Bapu was extremely active as a poet and writer, and started a magazine—Srujana. He formed a collective of revolutionary writers called Virasam. This has been a glorious contemporary history of radical literary activities in Telugu.

My two sisters and I grew up in an environment where magazine meetings used to be held at our place. Political discussions and poetry were part and parcel of growing up. He never enforced any values he believed in upon us, but it was difficult not to have his influence on us while growing up. My sisters and I embraced the values he always stood for. A simple lifestyle and commitment to political activism became an integral part of all of us.

Bapu worked a lot—he edited magazines and actively engaged with literary and political movements, including the struggle for a separate Telangana movement. Alongside his academic career, he emerged as a prominent figure in modern and revolutionary Telugu literature. He founded and edited the literary magazine Srujana from 1966 to 1992, which became a key platform for radical and progressive writers. He also played a leading role in founding the Revolutionary Writers’ Association (Virasam) and was associated with several other cultural and democratic organisations. During his imprisonment, my mother Hemalatha used to be the editor of Srujana magazine.

But all this came at the cost of constant fear for his life and arrests. Our magazine was banned twice. My mother was given rigorous sentence for two years, sent to jail as convict in the magazine case, but later given bail by the High court after 8 days on appeal and eventually acquitted. Police used to knock on our doors anytime, looking for my father. It was so routine that sometimes we would be home at night but not the next morning. When I would ask about him, my family would tell me that the police had arrested him. I would ask about his whereabouts and go back to sleep.

People in our neighbourhood in Warangal used to respect him a lot. They knew that if he was arrested, he must have done some good work, mostly for the poor. But in Maharashtra, a political prisoner was looked down upon and treated differently.

Meeting him in jails or courts meant trips from Hyderabad to Pune and later Mumbai, bearing heavy expenses. Even today, when is out on bail but confined in Mumbai due to his bail conditions, it is difficult for my mother Hemalatha to live with him in a city where they had to struggle to find an apartment.

From the early 1970s onwards, my father faced repeated state repressions, irrespective of political regimes. Over a period of 45 years, he was arrested multiple times and booked in numerous cases under serious charges, including sedition and conspiracy. None of the cases resulted in a conviction, but he ended up spending several years in prison as an undertrial. His prison terms coincided with some of the most productive phases of his writing and translation work.

I proudly carry his legacy forward. I remember an incident when he told me, as a lecturer, you should present yourself with simplicity in front of your students. “You can develop any style of clothing or appearance, but you should remain simple. The day students pay more attention to your attire or style, it may distract them from your teachings. A good teacher should ensure that students pay more attention to what he/she is teaching and not anything else,” he would say. This is one of the biggest lessons I follow.

His uprightness for truth is another big learning for me. Do everything with conviction and truthfulness; no need to hide the truth, fearing consequences, he would say. Nothing was preached to us; these were everyday, casual learnings. Bapu was never afraid of his political identity, come what may. He was aware that structures that repress decent would end up in his incarceration, but that did not bother him.

Despite facing repeated incarcerations as a political prisoner and state repression, he continues to smiles bright like sunshine, because of the values he and we believe in. His uncompromised socio-political stand and work inspired hundreds of young minds. Prison confines people physically, which affects their physical and mental health for many reasons—one of them being the dystopian realities inside prison—but it can’t confine the souls, the truth, a spirit of fighting for values. No prison in the world has the power to confine my father’s dream of a society based on equality.

(This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Varavara Rao| Out on Bail, But Living in Exile dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent)