The accused include Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, Gulfisha Fatima, Meeran Haider, Shifa-ur-Rehman, Mohd Saleem Khan, and Shadab Ahmed.

The prosecution frames the riots as a planned conspiracy, defence lawyers argue it was peaceful protest criminalised.

The case underscores broader tensions in democracy around dissent, law, and civil liberties.

Delhi Riots Case: Supreme Court Denies Bail To Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam

Over five years after the February 2020 violence, five of the seven activists have been granted bail. However, Khalid and Imam have been denied.

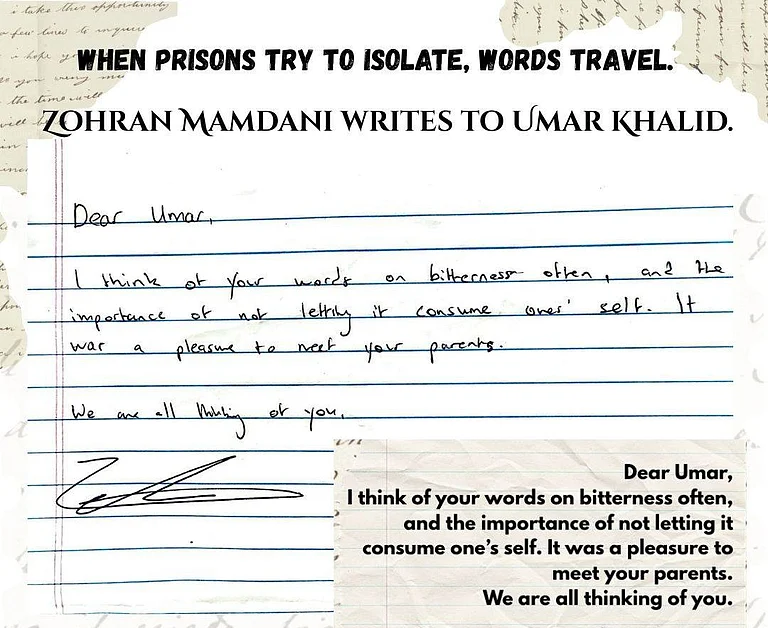

“Dear Umar, I think of your words on bitterness often, and the importance of not letting it consume one’s self… We are all thinking of you,” reads the handwritten note from New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani to Umar Khalid. The student activist has spent more than five years in prison under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) as their trial is yet to meaningfully begin. The brief message conveys more than solidarity. It’s a reminder that behind the charges and courtroom arguments lie human lives suspended in uncertainty.

Gulfisha Fatima, Meeran Haider, Shifa-Ur-Rehman, Mohd. Saleem Khan and Shadab Ahmad have been granted bail. However, Khalid and Sharjeel Imam have been denied bail.

Delhi Police asserted that the riots were not spontaneous and describe it as a part of “larger conspiracy” case that places these students and activists at its centre. After hearing challenges to the Delhi High Court’s refusal to grant bail, the Supreme Court is set to pronounce its judgment on their bail pleas.

As the bench of Justice Aravind Kumar and Justice N.V. Anjaria weighed arguments, the case has transformed into something larger than individual guilt or innocence. As the accused maintained they were part of peaceful democratic protest and not architects of violence, the case highlights the tension between dissent and criminalisation.

The Mamdani letter frames the story not just as a legal battle but as a moral and emotional one. It reminds the world that law, politics, and empathy come together in complex ways for those at the centre of such cases.

Inside the Conspiracy Claims

This case revolves around whether the February 2020 Delhi riots were the result of a pre-planned conspiracy or they were an outcome of communal tension that spiralled out of control.

Delhi Police allege that the riots were not spontaneous. They were a part of a structured conspiracy linked to anti-CAA protests. According to the prosecution, a section of activists and protest organisers used protest sites and speeches as a façade for something more sinister. They also used community mobilisation in a deliberate attempt to provoke violence, cripple the city, embarrass the government and internationalise the political moment, holds the prosecution.

The investigation frames the riots under a broad “umbrella conspiracy” theory. It claims that activists coordinated road blockades, escalating confrontations and logistical planning through meetings, WhatsApp groups, speeches and mobilisation networks. For this, the police invoked IPC conspiracy provisions and the UAPA, a law normally associated with terrorism.

Rejecting the narrative, the accused argue that they were part of India’s rich democratic tradition of peaceful protest. They insist that dissent was turned into a criminal act because it challenged power. Defence lawyers argue that there is no direct evidence linking the accused to acts of violence, no recovery of weapons, and much of the case rests on hearsay, selective witness accounts and interpretation of speeches and chats.

Those on trial

The seven individuals, each with distinct journeys, became central figures in a legal saga that has outlasted the riots themselves.

Khalid, raised in Jamia Nagar and a doctoral scholar in Modern History, had already become a polarising voice in national debates before 2020. He was known for his work co-founding United Against Hate and was arrested on September 13, 2020, under UAPA and conspiracy charges.

His counsel Kapil Sibal has pointed out, repeatedly, he was not in Delhi when the riots erupted. Khalid’s speeches advocating for peaceful protest later became a focal point of prosecution claims.

In January 2025, Amitav Ghosh, Naseeruddin Shah, Romila Thapar and 160 others wrote: “Deeply disturbed… [Umar] Khalid, known for his eloquent speeches advocating pluralism, secularism and constitutional values, has been repeatedly targeted, vilified and branded… falsely accused of conspiring to incite violence”, demanding release of CAA protesters.

Imam, from Bihar and educated at IIT Bombay and JNU, was taken into custody on January 28, 2020, weeks before the riots occurred. His arrest centered on speeches during anti-CAA protests. He became emblematic of the prosecution’s contention that public rhetoric helped fuel unrest, a claim his lawyer, senior advocate Siddharth Dave, consistently contested in court.

Fatima, a radio jockey with an MBA, was arrested on April 9, 2020. Represented by Senior Advocate Dr Abhishek Manu Singhvi, she has highlighted the absence of any direct link to violence, arguing that her detention reflects a broader pattern of criminalising participation in protest spaces.

Singhvi told the Court that Fatima has been in custody under 6 years now and is the only lady who has not been granted bail for allegations similar to and much lesser than those attributed to co-accused Devangana Kalita, Natasha Narwal, who were granted bail as early as 2021. He also submitted that the “great argument” of regime change nowhere appears in the main chargesheet and the four supplementary chargesheet, the latest of which was filed in 2023.

Singhvi remarked that her bail application was listed 90 times, 25 times the matter was not taken up due to the unavailability of the bench and 26 times, the matter was renotified. He termed this a “caricature” of the justice system and averred that no public interest would be served by keeping the 32-year-old lady in custody that long.

Meeran Haider, Shifa-ur-Rehman and Shadab Ahmed, similarly accused, have highlighted gaps in evidence and shifting prosecution narratives through their counsel, including Senior Advocate Salman Khurshid for Shifa-ur-Rehman and Advocate Gautam Khazanchi for Mohd Saleem Khan.

Legal stage

The case stands at a crucial stage. The courts are examining bail pleas and the strength of the prosecution conspiracy narrative under UAPA and other criminal provisions. UAPA reshapes the meaning of bail. Normally, in criminal law, bail is the rule and jail is the exception. Under UAPA, the logic flips. Courts are required only to see whether the allegations appear “prima facie true”, not whether they are proven beyond doubt. This makes bail extraordinarily difficult. And often resulting in prolonged incarceration without a completed trial.

Many accused have already spent years in jail without conviction. Trials in such complex conspiracy cases are slow. The prolonged pre-trial detention itself has become a legal and moral question. Should individuals remain imprisoned indefinitely on allegations that are still contested as the full trial timelines remain uncertain?

The prosecution, meanwhile, continues to rely on communications, speeches, alleged coordination networks and witness testimonies to claim a structured conspiracy. Defence lawyers counter that the case rests on assumptions, weak witness accounts, and political motivations rather than concrete criminal acts.

So the legal stage is not just about deciding bail applications, it is also about determining how courts interpret UAPA in protest-related cases, what standard of evidence should justify extended incarceration, and whether dissent can be legally framed as terrorism.

The court on Monday has granted bail to five of the accused: Gulfisha Fatima, Meeran Haider, Shifa Ur Rehman, Mohd. Saleem Khan and Shadab Ahmad.

Protests and Polarisation

In late 2019 and early 2020, India was engulfed in unprecedented political mobilisation following the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and discussions around National Register of Citizens (NRC). For many citizens, particularly Muslims, students, and civil rights groups, the law symbolised exclusion, and anxiety over belonging.

Sit-ins, marches and protest gatherings emerged across the country. Shaheen Bagh became the defining symbol. It was women-led, peaceful, determined, refusing to leave despite pressure and hostility. University campuses including Jamia, JNU, Delhi University, turned into spaces of debate, mobilisation and confrontation. Speeches, slogans and citizen participation created both solidarity and tension.

The political environment, simultaneously, turned deeply polarised. Counter-mobilisations emerged. Television studios amplified divisions. Street anxieties turned sharper. Delhi, already a political nerve centre, felt this tension intensely. By February 2020, the city was a fragile landscape of anger, fear and political contestation.

In such a heated climate, even minor triggers could escalate into the riots in North-East Delhi. It was not occurring in isolation. It was growing out of months of contesting narratives of nationalism and citizenship, and a battle over who belongs and who decides.

The State’s Case

At the heart of the prosecution case before the Supreme Court was the contention that the February 2020 violence was not an accidental eruption but the outcome of a well-orchestrated conspiracy.

Additional Solicitor General S.V. Raju and Solicitor General Tushar Mehta presented this narrative with a sense of strategic coherence, emphasising meetings, speeches, digital communications and organised mobilisation as evidence of an overarching design rather than spontaneous unrest.

Videos played in court, including snippets of speeches by Sharjeel Imam advocating citywide chakka-jams and disruptions in supplies across Indian cities, were cited to demonstrate intention and encouragement of mass agitation. The prosecution argued that this fed into a broader scheme to paralyse governance and public order.

Likewise, Umar Khalid’s presence at various gatherings at locations like Shaheen Bagh, the Indian Social Institute and other sites in the lead-up to the riots, was interpreted by the state as evidence of coordination, not coincidence.

The prosecution also relied on protected witness statements, WhatsApp and Signal communications, and call detail records to paint a picture of networked planning. In their view, financial channels, digital coordination, and meetings between groups like the Delhi Protest Support Group demonstrated not merely shared outrage but shared strategy and execution.

ASG Raju argued that such strands of evidence, viewed through established principles of conspiracy law, cleared the “prima facie” hurdle necessary to deny bail and proceed with a substantive trial. This procedural position underscored the legal and evidentiary complexity that now defines the case.

Defence Arguments

Defence counsel for the accused have argued that the prosecution’s narrative reads activism as criminality and thus misuses the provisions of the UAPA.

In court, Sibal, emphasised that Khalid’s speeches, including the one made in Amaravati, advocated for Gandhian, peaceful protest and could not reasonably be construed as instigating violence.

Sibal pointed out that chakka jams and other forms of non-violent agitation are part of India’s democratic lexicon and cannot be elevated to UAPA-level offences merely because they make authorities uncomfortable.

Senior Advocate Dave, arguing for Imam, questioned the very premise of linking speech to conspiracy, reminding the court that Imam had been in custody on separate charges before the riots and that there is no direct causal connection between his words and the violence that followed.

Dave also rejected labels such as “intellectual terrorist” as legally untenable and constitutionally problematic, reaffirming the presumption of innocence.

Singhvi, for Fatima, highlighted procedural issues like her bail application was listed repeatedly and often not taken up. He challenged the credibility of evidence, which, he argued, relied heavily on statements of protected witnesses and lacked any nexus to actual violent acts.

Khurshid, for Shifa-ur-Rehman, stressed that no funds alleged to have been received or disbursed by his client were ever recovered, making the financial conspiracy claim unsubstantiated.

In Shadab Ahmed’s case, defence counsel pointed to the shifting prosecutorial stance on physical presence at riot sites as indicative of narrative expansion rather than evidentiary solidity. Across the defence, the overarching assertion was that legitimate democratic expression and organisation have been legally conflated with criminal conspiracy.

Centrality of UAPA

The UAPA is not just a legal provision in this case. It’s the foundation on which the entire prosecution stands. It’s the reason that the accused continue to remain in prison for years without trial. UAPA was designed primarily as an anti-terror law. It’s meant to deal with extraordinary threats to national security. By invoking it in the Delhi riots conspiracy case, the state placed the protests and alleged planning in the same legal category as terrorism.

This changes the stakes. Under ordinary criminal law, the principle is simple. Bail is the rule, and jail is the exception. But under UAPA, the logic reverses. Courts are required to deny bail if the accusations appear “prima facie true”. Even before full evidence is tested in trial.

This standard gives the prosecution considerable space to present narrative-driven arguments, reliance on protected witnesses, broad interpretations of conspiracy and intent, and digital trails that may not directly prove violence but are claimed to indicate “planning.”

Defence lawyers have repeatedly argued that UAPA has been stretched beyond purpose, criminalising dissent rather than addressing terrorism. They stress that no recovery of arms, no direct acts of violence and no proven financial trail have been shown against many of the accused.

The Case: Legal or Political?

On paper, this is a legal case within the formal structure of the justice system. But it’s impossible to detach it from politics. The Delhi riots were not happening in a vacuum. They occurred at a moment of intense national debate over citizenship and state power. The accused were not random individuals. Many of them were prominent figures in the anti-CAA movement.

Their lawyers repeatedly argue that what is being presented as conspiracy is essentially political dissent framed as criminality. Sibal called it a case where “dissent is being weaponised as terror,” while Dave argued that strong speech, even provocative speech, is still within the boundaries of constitutional rights unless it directly instigates violence.

For the state, the case is presented as a defence of public order and national stability. They argue that protests crossed into deliberate destabilisation with intentional disruption and planning designed to paralyse governance and provoke unrest.

Civil liberties groups, academics, international observers and sections of the media frame this as a defining moment for Indian democracy. The prolonged imprisonment of students and activists, without trial, is seen as part of a larger conversation about shrinking democratic spaces.

While early outrage about the case was loud, recent silence underscores UAPA’s chilling effects, despite SC’s speedy trial concerns.