“Come meet me, beloved, when will you come?” (Aao milo sajna, kab miloge?)

Voices From Prison: Who Stole My Youth? Asks North-East Delhi Riots Accused Mohammad Iqbal

A Delhi district court granted Mohammad Iqbal bail in the riots case within three months. On March 18, 2025, he was discharged in the Babbu murder case, even as the riots trial continues

The words were carved into the wooden plank before it came crashing down on Mohammad Iqbal’s legs. Again. And again. In the police station that night, the message felt like a taunt, mocking and almost intimate, etched into the same object used to break his body. Years later, the pain remains, marking for him a life divided into before and after that night. Iqbal was arrested on March 7, 2020, nearly two weeks after the violence in northeast Delhi had subsided. He stepped out to buy meat, despite his mother’s warning, and at the last moment took a different lane at a friend’s suggestion. “I regret that moment to this day,” he says quietly. “If I hadn’t changed the route, I wouldn’t have been picked up.”

That friend was released early. Iqbal wasn’t. The police detained him and others, accused them of pelting stones at a house Iqbal claimed he hadn’t heard of, and then beat them up. “I screamed louder, hoping that they would stop,” he recalls. He was arrested the same day and sent to jail on March 8, 2020. What followed were eleven months behind bars and a murder charge added just when he thought he was about to walk free. He sits in a small room on the terrace of a congested four-storey building, clothes hanging from nails in place of a cupboard. This was his mother-in-law’s house, where he lived after his marriage in 2023, before moving to a nearby slum that costs Rs 3,000 a month. The move, he says, was driven less by money than by trauma.

Life after jail was harsher than he had imagined. Work was irregular, with networks destroyed by the riots. Some weeks brought two days of labour, others none. His mother had already spent heavily on bail and surety in a case still inching towards closure. “In criminal cases, when a court grants bail, it fixes a surety amount, say, Rs 25,000. The person standing surety must prove solvency of at least that amount, through movable or immovable assets or a fixed deposit,” explained advocate Abdul Gaffar, who was also the counsel for Iqbal in both cases. For families already living on the edge, arranging this money often means draining whatever little they have.“My parents are old now. They used to get frustrated that I wasn’t earning even after coming out of jail, especially my mother,” he says. “In the heat of the moment, she said many times that she would put me back in jail if I didn’t earn enough.”

The tension continued until he moved out. But that was not the only reason. “People in the area and the police look at me with suspicion. If anything happens in and around the area, they will pick me up. So I moved away with my wife and daughter,” he adds, as his daughter plays with the keys of the battery e-rickshaw he now drives. “Living in that slum is better than being reminded every day of what has happened to me in the past,” he said.

The early days at the slum were bare. “We didn’t even have plates,” his wife, who did not wish to be named, says. “There wasn’t a proper place to sit. We used to eat directly from the polythene the food came in, and then throw it away.”

The debt still weighs on them, between Rs 1 and Rs 1.5 lakh, most of it borrowed simply to survive. Yet, there are lighter moments. The birth of his daughter, he says, altered something fundamental. “Life became beautiful.” A few months ago, he rented a battery rickshaw, paying Rs 500 a day. On good days, he earns between Rs 800 and Rs 1,000, just enough to keep going.

A Delhi district court granted Iqbal bail within three months and, on March 18, 2025, discharged him in the Babbu murder case, though proceedings continue. “The statements of the witnesses and the video of the incident show that the members of the mob of persons from the Muslim community had no role to play in the beating of victim Babbu. Rather, they were sympathisers of the victim,” the court noted in its order, a copy of which Outlook has seen. But by then, Iqbal had already lost nearly a year of his life.

In those early weeks inside jail, he hoped he would be discharged and return to his village. When bail finally came in the riots case, his family gathered outside the jail gate. His mother waited there all day, convinced her son would walk out any moment. Instead, jail officials told them another case had been added. Murder. Disbelief gave way to a quiet, hollow despair. “Every day we thought—today, tomorrow, the next day.”

Then the lockdown began. Everything froze.

The cell was overcrowded to the point of suffocation. Sixty men were crammed into a room meant for ten. In the peak of summer, the heat became unbearable. Prisoners poured water onto the floor just so they could lie down. Days followed a numbing routine: brief moments in the sun, then lock-up again. A television played the same soap operas on loop. No news. “I felt like a parrot in a cage,” Iqbal says, his eyes fixed on the thin mat on the floor where he sits.

During Ramzan, food arrived around 3 am for sehri; iftar came late evenings. He said he had no complaints except that he kept 29 fasts, breaking just one. “It was too hot. I drank water,” he admits with a small smile. Eid came without chicken, it wasn’t allowed. Instead, they were served soya chaap. Iqbal laughs as he remembers it. “It was biryani with rice, peas, and butter. Very simple. We were fine with it.”

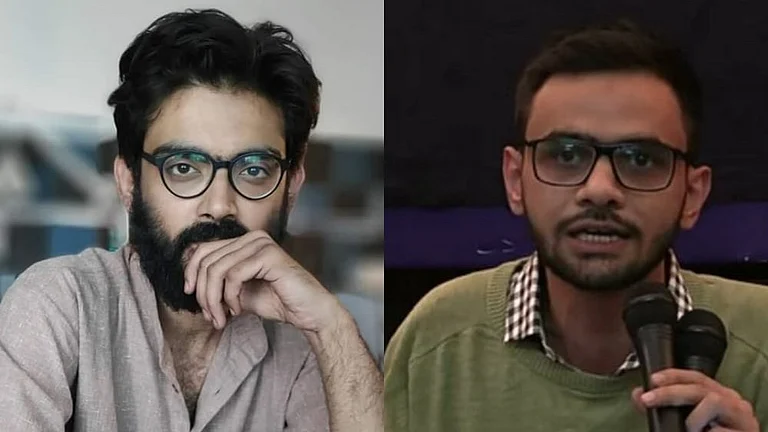

It was inside this jail that he met Khalid Saifi. He remembers how he led Friday prayers, organised Ramadan routines, and guided Eid meals. Umar Khalid, he says, spoke gently and expansively. He translated verses from the Quran, explained them in simple language, often to non-Muslims. “Even people who weren’t Muslim would listen and start crying,” Iqbal recalls. “There was respect. No one spoke badly to anyone.” He mentioned how Khalid often reassured them. ‘You will get out,’ he would say. If not today, then tomorrow. That hope mattered.

Still, hope was fragile. “In eleven months, at least two or three people died by suicide,” Iqbal says quietly. He heard stories of men hanging themselves, crushed by uncertainty. The thought, he said, never crossed his mind. “I didn’t want to be one of them,” he says. “I kept thinking, somehow, I have to go home.”

Advocate Gaffar, who handled nearly 100 northeast Delhi riot cases, says Iqbal’s experience was typical. He argues investigations lacked scrutiny, noting that chargesheets rely on sweeping “chronologies” that collapse disparate protests into a single, unexamined narrative. The law permits only material discovered during investigation to be included in a chargesheet. “Here, entire paragraphs are written without investigation, without evidence,” Gaffar said. “This reflects a pre-decided notion to reach a particular conclusion.”

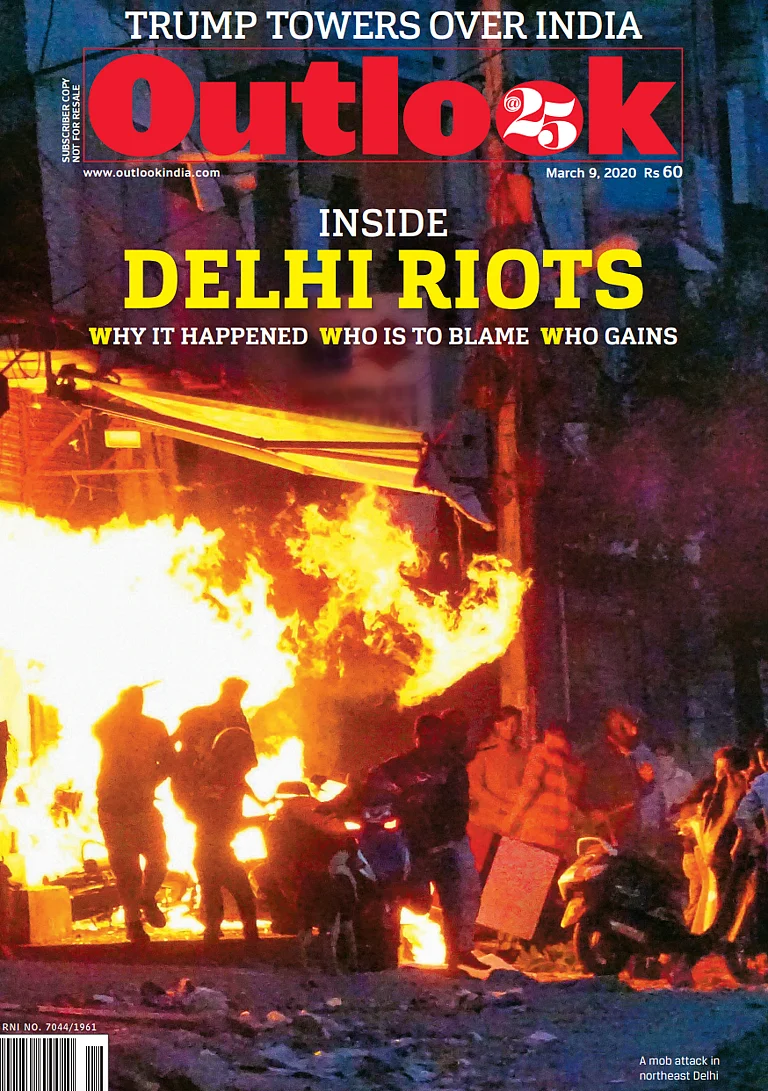

The 2020 northeast Delhi riots erupted on 23 February, centred on areas such as Jaffrabad, Maujpur and Chand Bagh, amid protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act and wider anxieties over the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the National Population Register (NPR). A sit-in near Jaffrabad metro a day earlier became a flashpoint, spiralling into mob violence involving arson, stone-pelting and shootings. Fifty-three people were killed and hundreds injured. Over 2,000 arrests followed, with nearly 100 FIRs. Courts later pulled up Delhi Police for shoddy investigations. In Iqbal’s case, the police initially even named Babbu, the deceased, as an accused.

Another man, arrested on murder charges on March 18, 2020, was granted bail only in 2021. The court discharged him in its final order on August 22, 2023, stating that there was ‘no concrete evidence and no sufficient material to frame charges against him.” He did not wish to speak in detail about his time in prison. “It was the worst phase of my life,” he says, requesting anonymity. “It turned everything upside down.” What remains with him are questions. “Why was I taken when they had nothing against me?” he asks. “The court proved me innocent, but who will prove that to people who still look at me like a criminal?” He pauses. “I can’t show my court order to everyone. Who will give me back what I lost during that time?” he asks.

Iqbal’s riot case is nearing its end. Another date is scheduled for the 19th. When it’s finally over, he knows what he wants. “I might leave Delhi altogether,” he says. Then, almost as an afterthought: “I don’t want this life anymore.”

The wooden plank with its mocking words, the one used to beat him, is gone. The pain remains. But what haunts him most isn’t the violence itself. It’s how easily a wrong turn, a rerouted path taken to buy fish, can reroute an entire life.

And how long it takes to find your way back.

Mrinalini Dhyani is a senior correspondent at Outlook. She covers governance, health, gender and conflict, with a strong emphasis on lived realities behind policy debates

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent

Tags