“Friends, therefore, I give you the National Party.” Thus spoke Dev Anand at a press conference on September 14, 1979, at the Taj in Bombay. He was there to announce the formal launch of a political outfit and the release of its manifesto. It was a strange but real event in the political history of India. Dev and his colleagues in the enterprise called their party a ‘crusade’ against the corrupt politicians of the country. And the crusaders were none other than our own film folks who wanted to “teach a lesson” to politicians, who they thought were a “pack of greedy fools, a motley crowd of self-seeking opportunists”.

The seeds of discontent were sown during the Emergency of 1975-77, when the entire film fraternity, like the rest of the nation, was subjected to humiliating treatment in various ways. Legendary stars like Dilip Kumar and others were forced to speak in laudatory terms about the state of Emergency. When Dev and Kishore Kumar refused to fall in line, they were banned on radio and Doordarshan. When Emergency was lifted and elections declared, the film fraternity came out in open support of the Janata Party, but soon enough they felt betrayed. When the Janata government fell, the leaders of the film industry decided not to support any political party but float an outfit of their own to cash in on the popularity of its stars.

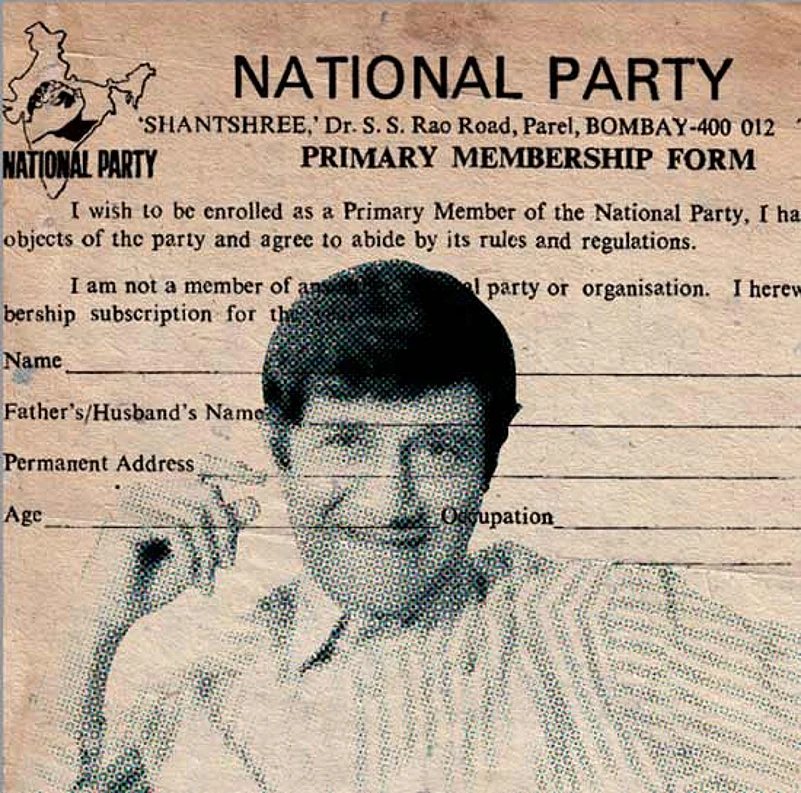

“Why not, for a change, and for the sake of the country we love, form a political party that would transform the ugly slushy shape of things and give it a new shape as magnificent and glittering as a grand film?” wrote Dev in his autobiography Romancing with Life. The assembly of film personalities like V. Shantaram, Ramanand Sagar, G.P. Sippy, Shriram Bohra, Atmaram, I.S. Johar and stars like Hema Malini, Shatrughan Sinha, Sanjeev Kumar and others chose Dev to lead the National Party. Several teams were formed by Dev and his colleagues, including his brother Vijay Anand, to draft the constitution of the party, launch a membership drive and create a manifesto for elections.

Membership was not a problem: thanks to the glamour attached to film stars, the drive drew a huge response from people across the country. Everyone thought they will be in the company of stars by paying a rupee as membership fees. While releasing the party manifesto, Dev, who looked every inch an angry young man, told the media that they were launching a crusade, “...a crusade against poverty, unemployment, illiteracy and corruption. A party to promote a prosperous and growth-oriented society.” The speech, in retrospect, sounds part Narendra Modi, part Arvind Kejriwal. But it did not get much media attention at that time: it was dismissed as another film promotion. But the fact remains that Dev at least was serious about this mission.

The launch was followed by a rally at Shivaji Park in Bombay, which, apart from film stars, was attended by the likes of Nani Palkhiwala and Vijayalaxmi Pandit. The huge crowds cheered the fiery speeches from the dais. Back-room boys were assigned the task of preparing a list of prospective candidates from the film industry and other spheres of society. The media was abuzz with all kinds of speculation—that Dharmendra would be pitted against Chaudhary Charan Singh, that Sharmila Tagore or Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi would contest from Bhopal, Dara Singh from Amritsar and so on. Many of them remained silent about these news reports; some denied them, as both the Janata Party and the Congress had started sending warnings to the National Party to keep away from elections. It was only actor, writer, director and producer I.S. Johar who remained unafraid. He went ahead and declared himself a party candidate against then Union health minister Raj Narain. He would not leave an opportunity to irritate Raj Narain. In an interview published in Debonair, he called him a joker in politics. “But,” he added, “the public would prefer me, because I am a much better joker than him.”

But then things started fizzling out fast. Producers, directors and actors who were initially at the forefront of the movement started shying away. The message from political parties was loud and clear—behave or face the consequences. With huge monies at stake, the film industry opted to behave rather than brave political wrath. That was ‘The End’ of the National Party.

Raajkumar Keswani is a senior journalist based in Bhopal