- Congress The party has offered support to the AAP, and unconditional too. But it has put the AAP in a spot: Can they be trusted?

- BJP The BJP has opted to sit out. It had done the pehle AAP. But AAP worries if they’ll pull the rug from under them soon.

***

Kaun Banega Mukhyamantri?

Arvind Kejriwal, 46

Former IRS officer

- Why: Is the face of the AAP. As CM, will enthuse voters and volunteers

- Why not: Becoming CM will tie him down to Delhi, curtailing expansion plans. Also, failures will be easily pinned on him.

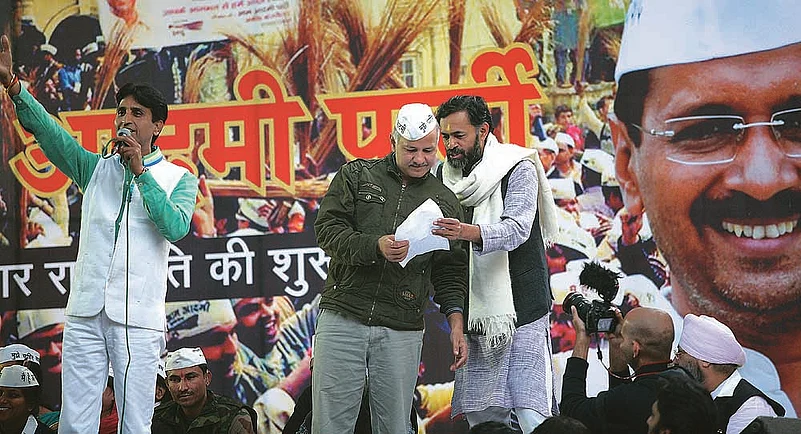

Manish Sisodia, 41

Former journalist

- Why: The second-most recognised face of AAP and is trusted by Kejriwal

- Why not: Not as articulate as Kejriwal and not as popular. The party rank and file is rooting for Kejriwal.

Rakhi Birla, 26

Former journalist

- Why: Youngest woman candidate to win in the Delhi elections

- Why not: Her age works against her. Plus, she is too much of an unknown, even within her own party

Yogendra Yadav, 50

Social scientist, psephologist

- Why: Respected psephologist, key player in crafting AAP’s intellectual framework

- Why not: Like Kejriwal risks getting bogged down in Delhi. Better off as a national leader

***

Closing in on a fortnight after the Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) stunning electoral debut, the political fog in Delhi was still brimming over with enough questions to fill a psephologist’s questionnaire. The most tantalising one is: will the AAP form the government? (The answer, we’re promised, will come as the Christmas week dawns.) And if that gets ticked in the affirmative, as seems likely, a new attendant question that has popped up suddenly too will demand an answer. Who will be the chief minister? All these days, the AAP’s list of CM candidates had been assumed to begin and end with one name: that of its talismanic chief convenor, Arvind Kejriwal. But who knows? Even within the party, an unknown aam aadmi might stand up. Or indeed, an aam aurat.

Difficult questions define the curious predicament the fledgling party finds itself in, and its response has been to lob those right back to the court of the people, in a striking extension of its experiments around participatory democracy. After days of pussyfooting by the BJP—during which it made a conscious display of a rare virtuous streak by saying no to power because of a slender numerical deficit—the initiative had passed to AAP. The defeated Congress, with nothing to lose, promptly played a double bluff, offering AAP the ‘unconditional support’ of its eight MLAs. This was no longer as simple as agitprop; a more ironic introduction to the complexity of realpolitik was difficult. After being brought thus far by virulent anti- Congressism, could AAP now stride into the treasury benches with its support? Political ethics, tactical edge, long-term growth—suddenly, everything was at stake in the next move it was called upon to make on the chessboard.

The AAP think-tank opted for a feint—it decided to pass on the onus of decision-making to the people who elected it. Adopting a Swiss-style referendum, it took to nukkad meetings, SMS polling and Facebook updates to divine the popular will. Lakhs of SMS answers apparently arrived over the weekend. The AAP leadership is clear: if the overall numbers are inconclusive, they will abstain from power. This reluctance stems from a deep distrust of the established parties—the AAP is in a bit of a quandary over the key question of whether to take the Congress’s word that its support truly comes with no strings attached.

At the AAP’s office in East Delhi, volunteers who had given their all to get the party to this juncture didn’t seem to want their new MLAs to wield power yet. This is a trap, they say. Newly elected MLA Manish Sisodia says, “There is a perception that saying no is easy and saying yes has its attendant risks.” What are the risks? Pat comes the reply from volunteers, the municipal bodies of Delhi are in the BJP’s hands. Will they allow us to work? That’s the dilemma.

More mundane, if urgent issues, interrupt the discourse on tactics. Someone raises a problem facing the neighbourhood: the drains are blocked. “These are problems, not proposals,” said Sisodia. “We should learn to distinguish between a problem and a proposal. Think of some proposals.” Glimpses perhaps of what filtering the well-meaning cacophony raised by volunteers for suggestions on governance will involve. After all, those who brought the party to power can’t be ignored: they must be respected, and some way must be found to elicit meaningful—and more important, usable—suggestions from them.

Indeed the party is grappling with an “inner dilemma”, as Kejriwal spells it out in his letter to those who voted the AAP to victory. “You tell us if we should govern or not,” Kejriwal and his colleagues are asking. They have time till Sunday to make up their mind and they will do so after the people have spoken to them. Is the AAP avoiding taking the difficult decision? “This is an issue of governance, as we don’t have the mandate,” says senior advocate and AAP member Prashant Bhushan. “It’s important we know what people want.”

This electoral battle in Delhi has seen so many firsts, everyone is confused. It’s the first time the no. 2 party is being asked, nay compelled, to form the government. It’s also the first time a party with the largest number of seats, conscious of being watched, has not tried to win over some politicians from other parties. It’s also the first time a people’s party within reach of power is being coy.

At the time of going to press, it’s not clear if AAP will form the government. Or if Kejriwal will be chief minister. If he does, will he have the time and mental resources to carry out the national agenda of the AAP—to make India catch the fire, so to speak? If they abstain, wouldn’t he be letting down those who have voted for him, and through him, for change? If not him, who?

The AAP can’t just give up; it has to be seen making the most of what it has. For the moment, the clean politics they intend to practise is very much on display. After all, the people have voted for the AAP in Delhi and it is to the people they have gone, not to power brokers. Over the weekend, besides the online means, leaflets are being distributed across households in Delhi. People are being requested to go through the points raised—and respond. Nearly six lakh people had responded by SMS as the magazine went to print. The AAP wasn’t reading them yet, waiting for them to be collated on Sunday. Meanwhile, its teams are fanning out from mohalla to mohalla. The 18 points raised by Kejriwal range from FDI in retail to regularising slums, “vip culture” to schools for the poor. Call it a referendum for government in Delhi. In the end, whichever way it decides, the party will have to bear the burden of responsibility: 2014 lies just beyond.

So far, for a party in its infancy, the AAP has made a series of audacious political moves, quite unorthodox in conception and fantastically successful in execution. Its very political birth was one such. If it forms a government in Delhi, it will have to hit the ground running, take crucial decisions on power and water and go with the report card into next year, to face the bigger challenge of the Lok Sabha elections.