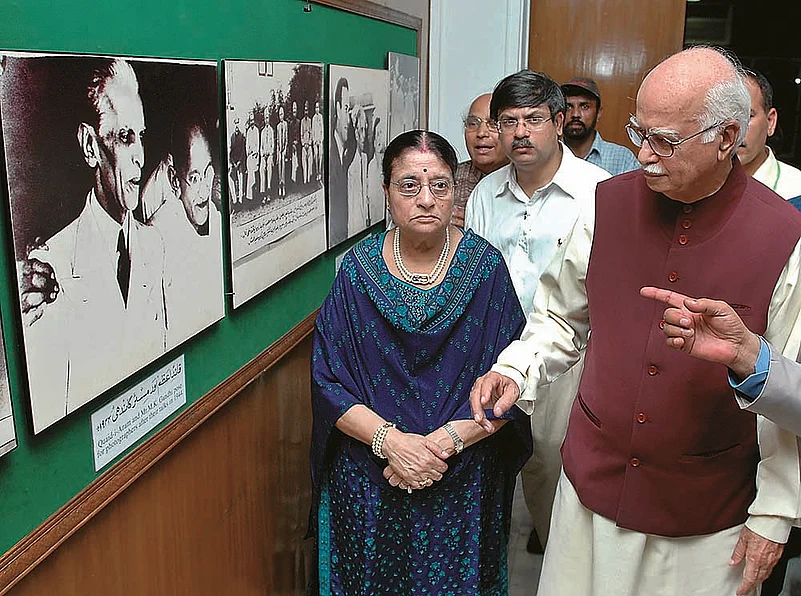

One sunny morning in Karachi eight summers ago, the marble mausoleum of Mohammed Ali Jinnah—disputably the sole spokesman of the Muslims of undivided India and undisputably the architect of Pakistan—had an unlikely visitor. L.K. Advani, then president of the BJP, was visiting his hometown only for the second time after he migrated from it at age 20 and for the first time with his family. What he inscribed in the visitors’ book was even more uncharacteristic: “There are many people who leave an inerasable stamp on history. But there are very few who actually create history. Quaid-e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah was one such rare individual. In his early years, Sarojini Naidu, a leading luminary of India’s freedom struggle, described Mr Jinnah as an ‘Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity’. His address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947, is a classic, a forceful espousal of a Secular State in which every citizen would be free to practise his own religion but the State shall make no distinction between one citizen and another on the grounds of faith. My respectful homage to this great man.”

Within minutes, news channels in India were flashing it: “Advani praises Jinnah, calls him secular”. I had accompanied Advani, and called a senior BJP leader in Delhi to convey the exact message, only to hear an angry rebuke: “Advaniji ko yeh sab kehne ki kya zaroorat thi? Yahan to tehelka macha hua hai! (Where was the need for Advani to say all this? It has raised a furore here!)”

It’s well known what happened to Advani and his party after that audacious journey to Pakistan. To his abiding credit, he has never withdrawn his remarks on Jinnah. Nor has the RSS, ideological master of the BJP, ever cared to explain why it thought his comments were wrong. The controversy over Advani’s observations on Jinnah may now be a thing of the past, but not the debate on India’s cataclysmic Partition, whose effects are still felt from Peshawar to Dhaka. None of the three sovereign nations that once constituted a united India has satisfactorily resolved the communal problem: Pakistan, which broke away on the basis of the spurious two-nation theory; Bangladesh, which broke away to disprove that theory; and India, still struggling to make its morally superior ‘idea of India’ a living reality. Obviously, the people of all three countries must delve into our shared and separate histories to find the paths to peace—within and across borders.

In such a study, Jinnah comes across as both a villain and a tragic protagonist of an idea backed by some Muslims in undivided India. Its core was simple: Muslims were a distinct people in India and should have, after the departure of the British rulers, an opportunity for free development in regions where they were in majority. This wasn’t a communal demand per se; it could have been implemented within a united India through a well-conceived, multi-tiered constitutional architecture. Had Congress and Muslim League leaders approached the issue with patience, foresight, a spirit of mutual accommodation and a firm commitment to the aspirations and democratic rights of all sections of our diverse society, Partition could have been averted. After all, there was nothing inevitable about India’s vivisection. In any case, the communal bloodbath and large-scale displacement of panicky populations could have been certainly averted.

The largest part of the blame for this tragedy must be borne by the British and the Muslim League led by Jinnah, who gave a communal colour and violent thrust to what could have been kept within the limits of a workable constitutional demand. Nevertheless, what partially redeems Jinnah’s role is one undeniable fact to which Advani rightly alluded in his Karachi remarks: both towards the beginning and the end of his political career, Jinnah genuinely stood for Hindu-Muslim unity. As is evident from his speeches on August 11 and August 14, 1947, his vision for Pakistan was secular. It was rooted in religious tolerance and equal rights for all. But the path he chose—Pakistan was the first nation raised on the basis of religion—was the antithesis of this vision. Unsurprisingly, today’s Pakistan has moved further away that vision.

Jinnah failed India. And Pakistan has failed Jinnah. Now it is up to our generation to set right the many failures of our subcontinental history.

(The writer, who recently quit the BJP, was a close aide of both Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani. E-mail: sudheenkulkarni AT gmail.com)