In 2016, the script looked completely different. Arvind Kejriwal himself led from the front, canvassing, holding massive rallies across Punjab—even hinting, perhaps not very prudently, at a switch from Delhi. NRI Punjabis flocked in support. Punjab would go the Delhi way, it was commonly presumed. Such confidence was never before seen in AAP: it boasted that it would win at least 100 seats in the 117-member assembly. Both the Congress and the Akalis, the twin poles of Punjab politics, felt threatened. Even long-entrenched figures like Parkash Singh Badal and Captain Amarinder Singh seemed to be looking nervously over their shoulder.

From there, the fall was painful. AAP won just 20 seats—and 25 of its candidates lost their deposit. Thus began a downward spiral that still continues. Eighteen months down the line, AAP is now falling apart in Punjab amid internal contradictions. The latest crisis is the removal of Sukhpal Singh Khaira as leader of opposition (LoP) in the assembly following allegations that he took bribes from party workers. A touch of déjà vu there—the party’s state convenor before the 2017 polls, Sucha Singh Chhotepur, too was sacked upon allegations that he took money from a supporter.

Khaira has been replaced by first-time MLA Harpal Singh Cheema, whose first challenge will be to put up a united face during the monsoon session in September. Cheema is the third LoP for AAP in Punjab. Khaira took over from Sikh rights lawyer H.S. Phoolka. Delhi deputy CM Manish Sisodia, AAP’s Punjab in-charge, announced Khaira’s removal via a tweet, which also carried the message: “party is bigger than posts”. Kejriwal didn’t speak on the issue till he was asked about it in Rohtak recently. “It’s a family matter...party will settle it,” he said.

The list of AAP deserters is long. Notable among them are Manjit Singh of the Yogendra Yadav camp, the late Daljit Singh, Lok Sabha MPs Harinder Singh Khalsa and Dharamvira Gandhi and comedian Gurpreet Singh Ghuggi. Then, in May this year, Kejriwal’s decision to issue an apology to end a defamation suit with former cabinet minister Bikram Singh Majithia made state president Bhagwant Mann and co-president Aman Arora to resign in protest, though their resignations were never accepted.

The exit of each leader also means a mini exodus of their followers. Khaira is said to have a large following in AAP. “Autocracy and dictatorship have taken over autonomy and the democratic spirit in AAP. We lost in Punjab as opportunism took over opportunity. The people were fooled. See what they did to me when I sought autonomy,” says Gandhi.

Ghuggi, who resigned in March, had backed Khaira, who is said to have the backing of seven MLAs. Khaira had raised a banner of revolt and declared the state unit as autonomous. The state unit moved quickly, seeking the suspension of Khaira and another MLA, journalist-turned politician Kanwar Sandhu.

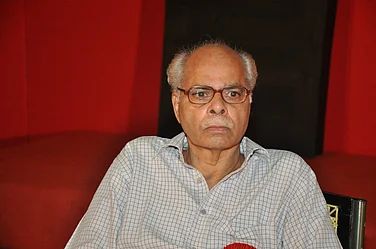

“A party without ideology has to rally around individuals and that creates challenges,” says Pramod Kumar, a social scientist at the Chandigarh-based Institute of Development and Communication. But now, many feel AAP is no longer about ‘individuals’ in a general way—just one man. A tweet from AAP Punjab’s official Twitter handle on August 2 says, “AAP derives strength from its volunteers, likewise every volunteer has only one hero i.e. Arvind Kejriwal.” It goes on to add, “No volunteer will support a person who tries to break the emotional thread between Arvind Kejriwal and his army”. The message is self-explanatory.

Arguably, the biggest disappointment has been to NRIs—particularly from Canada—who had come in hordes to campaign for AAP last year. “The same rot has set in the party that afflicts others,” says Mandeep Singh from Brampton. Jagtar Singh Sanghera, AAP’s NRI wing convenor, feels there is an urgent need to “evaluate what went wrong and where”.

By G.P. Singh in Chandigarh