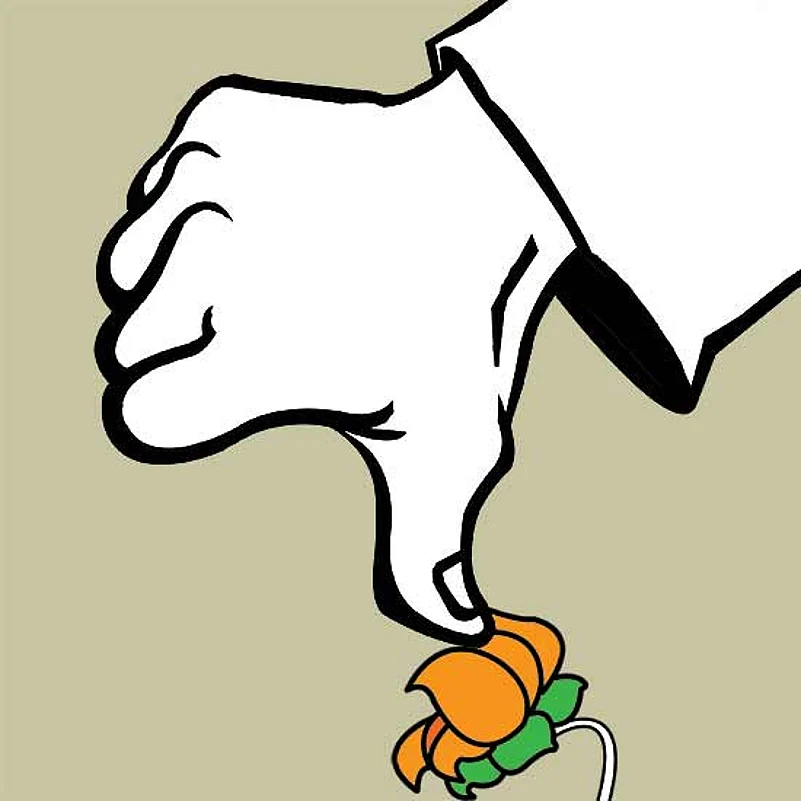

After 25 years, the Sangh parivar’s so-called ‘gateway to the south’ stands firmly shut. Considering the scale of debacle, this isn’t a temporary setback. The BJP has lost two-thirds of the assembly segments from what it won in 2008 and its voteshare has fallen by almost 40 per cent. A facile explanation for the defeat might blame persistent dissidence in the BJP in the past five years, and the two splits last year that led to the formation of B.S. Yediyurappa’s Karnataka Janata Party (KJP) and B. Sriramulu’s Badava Shramika Raitha (BSR) Congress. That explanation has some truth: figures show that between the two of them, the KJP and BSR Congress received more than 12 per cent votes, which is close to BJP’s 14 per cent loss.

However, these numbers alone do not explain the BJP’s troubles. Even before the elections, the party couldn’t find credible candidates in nearly one-fourth of the constituencies. Many candidates lost their deposits. And not one-third of the winners are core Sangh parivar activists. Does this defeat then signify the failure of the grand Sangh parivar experiment in Karnataka?

Please note: Despite the BJP’s intentions, the great Karnataka experiment was anything but a Hindutva one. True, the BJP depended on its core urban Hindu support, but its success from 2004 onward was the result of a social coalition of Lingayats, several neglected OBC groups and some Dalit groups. However, the social coalition acquired potency only in association with the money power from mining. Gali Janardhana Reddy and his Bellary associates injected huge amounts of money in the Bellary area during the 2004 assembly elections. By 2008, the practice was widespread, with real estate and mining money influencing election outcomes. Sriramulu was an example of the new BJP leader’s profile: caste appeal plus money power. In fact, it was new leaders like him who dominated the BJP governments in Karnataka, much to the chagrin of core Sangh types. Even when practised, the Sangh parivar’s aggressive stance against the minorities and women backfired spectacularly, as the evidence from coastal Karnataka amply demonstrates.

In 2012, the BJP’s social coalition fell apart and the mining lobby found itself severely constrained through Supreme Court interventions. As splits occurred, the BJP continued to offer delusional arguments claiming that the corrupt elements have left, and the newly cleansed party would now follow Modi’s Gujarat model. However, with a five years’ governance record to examine, the people of Karnataka haven’t bought that claim. Despite some achievements like the Bangalore Metro and Sakala (right to guaranteed services), the BJP in Karnataka didn’t have a development narrative like Modi did. Its governance seemed limited to welfare programmes (mostly distributing cash and subsidies to caste groups and mathas) and politically symbolic measures like having a separate agricultural budget. Far more damaging was the behaviour of its leaders. The corruption cases that came to light were trouble enough. But facing accusations of favouring their own family members, BJP leaders, including Yediyurappa, asked if the children of politicians shouldn’t run business. Some BJP members were embroiled in sex scandals; some others were caught watching porn clips in the assembly. The voters were not amused.

Now, the challenge for the BJP is to build a new social coalition. That will still revolve around Lingayats, and a combination of backward castes in addition to its core urban Hindu base. However, the BJP will have to ensure that such an expansion is grounded in some political morality. It will also have to ensure that the cohesiveness of the party doesn’t come from only money and the desire for power. This will become evident if they pay attention to one aspect of the Congress victory: the drama over ticket distribution may have dominated the media narrative, but in the end, the winners have turned out to be veteran administrators with relatively clean images. The BJP list sorely lacked such figures.

Another point: the party’s rebuilding plans will have to take on a local flavour. Even for the upcoming Lok Sabha elections, the BJP cannot simply hope to adopt a national strategy, especially one that depends on Hindutva or on Modi’s Gujarat model. Even Modi will admit the importance of the social coalition he has built for his success. In any case, a political argument based on good governance is effective only after people have experienced such governance. Polarising figures like Modi can only hope to raise the enthusiasm of the party core. If the BJP wants to expand its social base, it will have to make a political argument—one that is a combination of local and national factors.

(The writer teaches history at the Karnataka State Open University.)