The Modifier

- After the 2002 riots, Modi projected Gujarat as an investor haven with Vibrant Gujarat meets

- Grey Worldwide, and then Apco Worldwide, hired to hardsell state

- Numerous MoUs signed, but not clear how many translated into projects on the ground

- Modi has cultivated an online and social media presence

- There are hundreds of Modi fans maintaining laudatory websites

- 3-D videography was a stunner

***

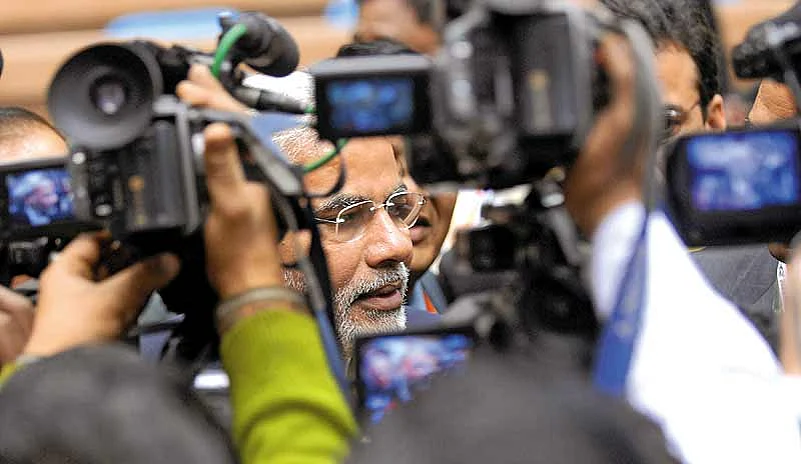

What’s common to actor Salman Khan and Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi? Besides the very visible maschismo they both display, there’s a story that unites them, one that Rajat Sharma of India TV likes to recount. Three years back, he put the chief minister of Gujarat in the dock on his programme Aap Ki Adalat, in which he subjects public figures to a mock trial after which a verdict is delivered. He says Modi drew a viewership of the kind drawn by stars like Salman Khan.

On Twitter, his following is equally strong. Modi has over 11 lakh followers, many genuine, some fake perhaps. There was a time he did not follow anyone; now, he follows 293 public figures, among them composer A.R. Rahman and former president A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, who pushes a ‘20/20 Vision’ for India. Modi has also built his image with a presence on TV screens, by running his website, by taking care of what he wears—and what he says, which is cultivatedly controversial. He pays particular attention to the visual presentation of his person: the 3-D projection was a force-multiplying campaign stunt, no doubt, but even before that, Modi had brought out booklets with shifting image covers that audaciously fused his image with that of Swami Vivekananda. The result of all these efforts is an image larger than the man himself.

Who funds his campaigns? Who pays for his publicity? The answers are somewhere out there. The methods, however, are reminiscent of the late Pramod Mahajan, another media-savvy BJP leader. Mahajan had tried to hardsell the ‘India Shining’ image through a campaign that however did not serve the NDA well. Modi’s machinery is trying to project a ‘Gujarat Shining’ image, with his eye and stride set upon the national stage. It is a telling comment of the age we live in that Modi and his event managers do not shy away from highlighting his ambition, which grows by the day.

“You cannot dismiss him. You cannot ignore him,” says Rajdeep Sardesai, editor-in-chief of CNN-IBN. “He’s a great communicator and also a polarising figure, which makes for great TV. He says and does controversial things. The sharp rhetoric makes him a natural for TV.” And Arnab Goswami, of Times Now, says, “Why TV alone? Even the print media uses up reams on Modi. The state sends 26 MPs to Parliament, Modi is ambitious, he’s on to a hat-trick, and it’s a Modi versus Congress fight.” Journalists are all agreed on Modi being a politician who is in a class apart—the sort who deploy the ‘Us versus Them’ rhetoric effectively. Of the media chasing such persons, Ashutosh, managing editor of IBN-7, says, “TV will follow Modi—as it did Laloo Prasad Yadav. It’s easy to categorise them: Laloo as secular, Modi as communal. Once they stop making news, the cameras will stop following them. But as long as they speak and act, followers and baiters and detractors will listen to them.”

Ashutosh also points out how both television and the print media have criticised Modi and never allowed him to forget 2002. “We do point out that Gujarat is 13th on the hunger index—that despite its vibrancy, its social indicators are in a bad way.” But he acknowledges Modi’s myth-building machinery that seems to negate such criticism.

Much of this negation is achieved by Modi’s presence on social media networks and by his supporters, who have pitched in to do battle for him in such forums. “We may not like the way he brings national issues to regional politics, yet in these elections the Congress and the BJP can be accused of doing the same. Call it asmita or whatever, he knows his urban constituency well, unlike Chandrababu Naidu,” says Prof Anil Gupta of IIM Ahmedabad. And Modi’s PR machinery churns out every little bit of information it can use to build a following, create a myth. Especially one that shows him up as investor-friendly.

It’s difficult to estimate how much money is being spent on such campaigns. Says an official from a PR firm, “The idea of selling Gujarat as a dream investment destination began soon after the 2002 riots, during which Muslims were targeted.” Worldwide tenders were floated by the Gujarat Investment Bureau with the objective of projecting Gujarat as an ideal industrial hub rather than a tourist destination. Apco Worldwide bagged the rights to do so, with the limited mandate of focusing on industry and investment. Simultaneously, Vibrant Gujarat summits, during with investors signed MoUs to set up units in Gujarat, were held: the sixth such meeting will be held next year. Some say the constant burnishing of Gujarat’s pro-business image has been responsible for the change of heart in countries like the UK, which at one time was unwilling to forgive Modi. NRI Gujaratis—traditional fund-raisers for the Conservative party—did their bit to bring people over. Eventually, James Bevan, the British commissioner to India, recently met Modi, ending a 10-year-old boycott of the chief minister.

So what is it about Modi that ensures not only viewership but also reactions that always border on the extreme? The answer is not exactly rocket science. Modi is seen as a sharply polarising figure whose presence naturally rebuffs tempered discourse, making him the perfect subject for television drama. Modi, and the 2002 anti-Muslim riots under his charge, are deeply etched in public memory and cannot be wished away. Add high-voltage development plans and endorsements for big-ticket investments by industrialists like the Tatas, Ambanis and Adanis—throw in an Amitabh Bachchan—and the image that goes out is a man who means business.

It is clear then that the media seems to seek out politicians who aren’t averse to showing off their ambition: it makes for riveting TV and sharp copy. Rajat Sharma got his interview after requesting the CM for years till he finally agreed. Among the many questions Modi was asked was if he had plans of leading the country. Modi had then said, “Abhi Advaniji hain, bhai! (Advaniji is still around, brother!).” From all accounts, that episode of Aap Ki Adalat was a huge draw with viewers. But despite the media blitz, the Gujarat election results—with 115 for the BJP, Modi hasn’t been able to better the party’s earlier record—show his appeal has its limits.

Corrected online: the print version of this story erroneously mentioned over one lakh followers, which was corrected to over 11 lakh.