As The Peat Burns

- CAG says 57 coal blocks allocated since 2004 would have earned Rs 1.86 lakh crore had there been bidding.

- Four of the 57 blocks are located in Congress-ruled Maharashtra; rest are in NDA/non-Congress states such as Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Jharkhand, Rajasthan

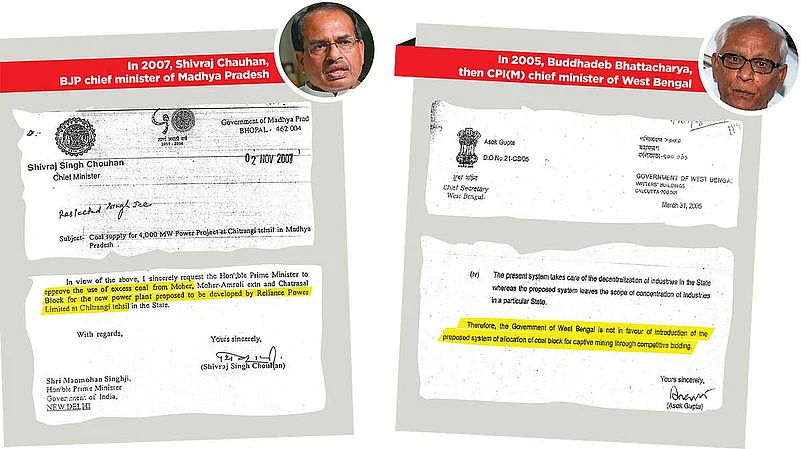

- Government sources point out that while the UPA wanted to introduce bidding, NDA state governments and Left Front in West Bengal opposed it

- CBI raids five firms. Among them is Congress MP and media baron, Vijay Darda, whose brother Rajendra is a minister in Maharashtra

- BJP demands summary cancellation of coal allocations; Centre says due processes and procedures must be followed, asks why CAG did not look at 32 blocks prior to 2004

***

Until the digging begins, one never knows the quality of the coal (or any mineral, for that matter) the earth will yield. A similar mystery is now unfolding overground—how and why were so many companies allocated coal mines despite not meeting the requisite criteria of financial strength or clear end-use project for which the captive mine was sought?

Actually, perhaps it’s not that much of a puzzle. People say this is the way things are (and have been) when it comes to our natural resources. The result is Coalgate, a scam where everyone is complicit, political parties of all persuasions, business houses, bureaucrats, you name it. The only loser, it seems, is the Indian state. Ask former petroleum secretary T.N.R. Rao about the system and he’s blunt: “The real Coalgate is that when you allot a mine, there is a quid pro quo. The CBI must look beyond allocation and misrepresentation. For, there is a difference when a politician acquires the block and gives it to some company and when politicians receive kickbacks.”

Of the dozen or so cases the Bureau is currently investigating, many are based on complaints by coal ministry parliamentary committee member Hansraj Gangaram Ahir. “In at least three cases, the company management changed soon after they were allocated coal blocks for captive use. In several others, the end-use plant doesn’t exist and no attempt has been made to get the mining work started in the last 5-6 years,” he points out.

The five cases in which CBI has so far filed FIRs this week bears out Ahir’s plaint. Documents and other evidence collected from 10 locations revealed fraud in all cases—whether in misrepresentation of management, financial strength, plan for end-use project or even the intentions of those seeking a captive coal block. As the CBI’s initial probe reveals, the trail of muck runs deep.

- Navbharat Power Pvt Ltd of Hyderabad is alleged to have colluded with unknown public sector officials to get a coal block in Orissa, misrepresenting information about other companies supporting the project. On allocation of two coal blocks in Orissa, one of the promoters allegedly sold his stake to Essar Power for Rs 50 crore. Later, the company’s shares were sold for Rs 12 crore “despite the company stake being worth Rs 85 crore”, CBI sources say. (Now Essar has stated that their dealings were above board, and they had bought nppl for Rs 230 crore.)

- Similarly, Calcutta-based Vini Iron and Steel Udyog Ltd not only changed management after being allocated a coal block at Rajhara in Jharkhand but were found to have used dubious methods to establish financial strength.

- Jas Infrastructure Capital Ltd of Calcutta was found to have given false representation, including hiding the fact that they already had five captive mines. The CBI is probing likely ‘bureaucratic connections’ in the case.

- In clear evidence of political clout, Maharashtra minister Rajendra Darda ensured that JLD Yavatmal Energy Ltd of Nagpur was allocated a coal block at Fatehpur East in Chhattisgarh for an end use power plant at Yavatmal in Maharashtra. The company is still to set up the power plant, which was to provide “free power” to the local people of Yavatmal. Sources in the Maharashtra government claim that such is the clout of JLD Yavatmal’s proprietors that when they suddenly decided to shift the proposed power plant to Chhattisgarh and were seeking a no-objection certificate, the official concerned received only a slip of paper—not a file—to authorise the demand. On not complying with the directive, the slip of paper was sent to another department to meet the same fate and from there on to the CM’s office.

- In the case of AMR Iron and Steel Private Ltd of Nagpur, the CBI has unravelled links with JLD Yavatmal Energy Ltd and Jas Infrastructure besides backing from Abhijeet Group and Lokmat, the regional media group, to get more blocks. This is despite having hardly exploited any among the nine blocks it’s already got.

It is indeed incomprehensible how despite a 15-20 member screening committee going through applications based on recommendations—and despite initial weeding out by state governments where the blocks are located—so many fraudulent cases were approved to mine valuable resources. Coal consultant U. Kumar says the problem is the lack of due diligence to verify whether the company seeking block allocation has the financial strength and end-use project.

Additional secretary, coal ministry, Zohra Chatterjee leaves an IMG meeting, Sept 3. (Photograph by Sajay Rawat)

The shocking part is that all this is happening while state-run Coal India Ltd is being pressurised to import coal to ensure supplies to private biggies, despite them holding captive mines. The list of biggies that have failed to make any progress with their captive mines include Rungta Projects Ltd, Contisteel Ltd, Dariwal Infrastructure Pvt Ltd, Dalmia Cement Ltd, Gujarat Ambuja Cement Ltd, Century Textile, J&K Cement Ltd, Birla Corporation, Benani Cement, Grasim Industries, Bhushan Steel Ltd etc.

“We’ve registered cases against unknown officials—and that includes bureaucrats and politicians. Investigations are on and many more cases may surface in due course,” says CBI spokesperson Dharini Mishra. And as the inter-ministerial group (IMG) too reviews the status of the 57 blocks where no work has been initiated despite lapsed deadlines, questions are being raised in scores of cases.

Doubts naturally arise as to why governments, both at the Centre and the state, failed to monitor the progress of mining activity (or lack of it) and kept silent even when evidence was brought to its notice. “Clearly, due diligence was not done. This is a little odd because people are careful in these cases because of CVC and CAG questioning. Whether this was a lapse or done intentionally has to be ascertained,” says a coal official.

Take just one instance. In a showcause notice to Topworth Urja and Metals Ltd in May this year, the coal ministry had questioned the multiple changes in the management of Shree Virangana Steels Ltd, the original allottee of Marki Mangli-II, III and IV coal blocks for captive use. “The allotment of coal blocks by the government is for captive purpose and is not for profiteering.... The sale of shareholding for profit defeats the purpose for such allocation,” the official letter reads.

There is enough evidence to show that change of management is not a one-off incident. “The assessment of the block and allottee should be done in such a way that such sales are not possible, but that isn’t done. Under the current corporate rules, transfer of ownership is difficult to bind down and people take advantage of that,” says a top ministry official. While selling the block alone is not possible, people have worked around that by selling the entire company (including end- use plant and mine). Unfortunately, there’s no provision in the policy to check this. Lack of a lock-in period for changing ownership is also a lacuna in policy.

One of the cases that’s caused the government major embarrassment is of SKS Ispat and Power Ltd with which Union tourism minister Subodh K. Sahay has come to be associated to get a coal block allocated. Minutes of screening committee meetings in ’08 reveal that SKS was allocated coal provision for fuelling a 1,000 MW integrated power and steel plant though the company’s plant is of only 600 MW capacity

All this matters because of the dramatic rise in coal prices after 2004, led by Chinese demand (the price of a tonne of coal is currently around $99-102, as against around $25-30 before ’04). Coupled with the increasing demand at home, the stakes have obviously risen dramatically for this heavily politicised natural resource. And it does make sense to rely on cheaper domestic supplies of coal rather than expensive imports.

Which is why many are now forcefully arguing that the system needs to change. Instead of bank guarantees, U. Kumar moots upfront payment as in Australia. Mines should also take land on high lease to tackle land acquisition issues. Given all the heat and dust around Coalgate, it appears the government is serious about cancelling blocks where no work has been done. But will it also send the right signal by encashing bank guarantees of those who flout the rules?

Docu-drama The CMs who wrote in opposing the auctioning of coal blocks

By Lola Nayar and Chandrani Banerjee with Arindam Mukherjee