***

Bharat Mata teri kasam

teri raksha karenge hum

(Mother India, we promise to protect you),

Deewaaren hum banenge Ma

Talwaaren hum banenge Ma

(We will be the walls, the swords),

Chhu le tujhko kismein hai dum

(Who will dare to touch you mother),

Vande Mataram, Vande Mataram

—Version of the historic song

written by Javed Akhtar during the Kargil war

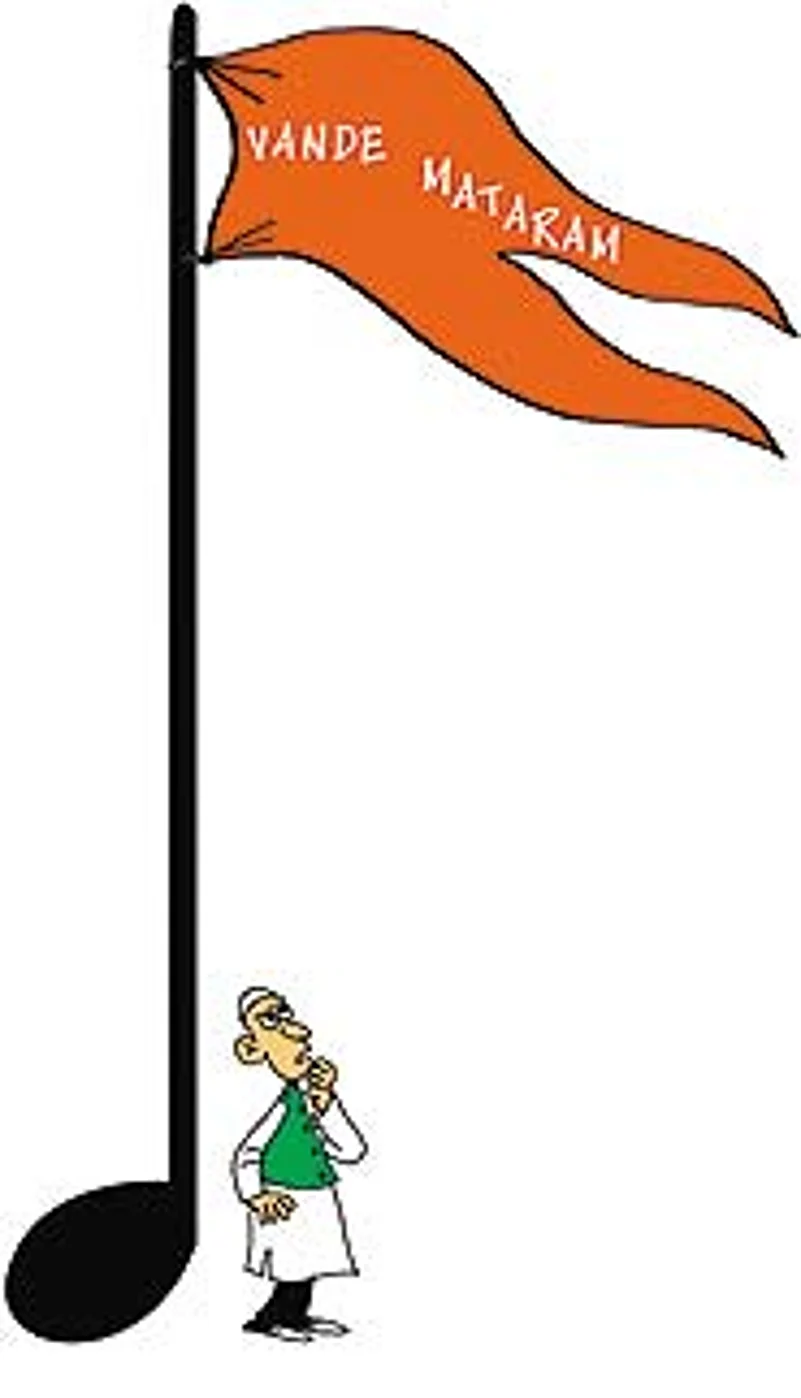

A comedy of errors in modern times over a song of historic vintage. More than anything else, the ongoing Vande Mataram controversy exposes the hypocrisy of all the players who have triggered and kept alive the debate—the Congress party, the BJP and the self-appointed spokesmen of the Muslim community.

Says Akhtar, who has composed three versions of the song: "The debate is a national shame. If this is an issue in a month where 105 farmers have committed suicide, then I doubt the nationalism of both sides." The punchline: "If a Deoband maulvi tells me not to sing, I will sing all the verses. If the RSS and the BJP insist I sing, I will never sing it."

So, how did India come to debate Vande Mataram yet again in 2006? As usual, bumbling along the path of secularism, the Congress first released the genie when Arjun Singh's HRD ministry issued a circular that the song be sung at all educational institutions on September 7 as part of its centenary celebrations. (Now there is a debate on whether he had got the date wrong.) Arjun, in the face of opposition from some Muslim clerics, quickly backtracked. "It was not a directive, but a mere suggestion," he told Outlook. "No one was being ordered to do anything." But by then the TV channels had coopted the episode to their never-ending "Muslim issue" circus.

Enter the BJP, whose many political failures have not deterred them from believing they are the sole guardians of Bharat Mata. The song must be sung, its spokesmen declared self-righteously, openly implying that Muslims refusing to sing were failing a test of nationhood. Lamentably short of real issues, party president Rajnath Singh got so excited by Vande Mataram redux that he shot off a directive to BJP-ruled states that all educational institutions must ensure the song is sung.

But high drama soon deteriorated into a farce. First it emerged that in 1998, the Kalyan Singh-led BJP government in Uttar Pradesh had sacked minister of state for basic education, Ravindra Shukla, for making Vande Mataram compulsory in all primary schools. Then prime minister Atal Behari Vajpayee had been livid with the minister.

Then realpolitik intervened in the path of Rajnath's glorious vision of madrassas et al singing Vande Mataram in patriotic fervour. Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan obliged, issuing separate directives insisting the song must be sung. Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat merely forwarded the Arjun Singh directive. Jharkhand did nothing because of the objections of ally JD(U).

BJP sources reveal there was also a rethink about a plan endorsed by Rajnath that 200 Muslims from the party's minority morcha sing Vande Mataram in Parliament on September 7. "The plan was absurd," says a senior leader. The reason trotted out by the party was they thought better of "segregating" Muslims. Yet the vision of the BJP setting up a ragtag Muslim choir invited its share of jokes.

The party remained confused about how to force someone to sing a song. Outlook asked spokesman Ravi Shankar Prasad whether he would expel students who don't sing, sack the principal, or send cadres to force Muslims to sing. His reply: "It's not a question of forcing people. But that, as Indians, everyone must sing." Ergo, those who don't sing are bad Indians.

What of the usual party poopers—the stubborn Muslims who refuse to sing in national harmony? As usual, the community had easily walked into a trap that questioned their nationhood. Matters were made worse by clerics and some politicians who raised Islamic objections to the song. In all fairness, the maulanas were being true to their understanding of the religion. For instance, Maulana Abdul Hameed Noumani of the Jamiat-Ulema-i-Hind that controls Deoband madrassas took the expected position. "Any Muslim who believes in Allah cannot endorse a song written in praise of a goddess. No one can force us to sing."

But press the good maulana further, and one gets an insight into very lateral thinking. Are qawwalis allowed by Deoband? "Not accompanied by instruments." But don't most Indian Muslims worship at Sufi shrines and love qawwalis? "Most Indians, including Muslims, are jahils (ignorant). They don't know correct Islam," is the spontaneous response.

The problem therefore lies in the complexity of the Muslim situation in India being reduced to a set of taboos by clerics who are approached by the media. Says sociologist Imtiaz Ahmad: "This controversy is political, not substantive. There is a convergence of interest between the BJP and Muslim orthodoxy. The more cornered the community, the greater the grip of the clerics. And because the Muslim leadership is prone to using religion as a pretext, they say Islam comes into it."

The real issue, say Muslims, is the insistence that they sing a song to prove their patriotism. Kamal Farooqi of the All India Muslim Personal law board says he doesn't want to give this issue a religious hue. "It is not about religion. It is about my religious freedom. I should have the freedom to sing or not sing."

Legally, no song, however hallowed, can be imposed on citizens. But the debate reflects the larger problem involving Muslim issues. With the spotlight increasingly on the community, their state vis-a-vis Vande Mataram can be summed up as damned if they sing, damned if they don't sing. In today's charged climate of suspicion, they simply can't turn around and say—what's in a song?