Starring: Nana Patekar, Dilip Prabhawalkar, Girish Kulkarni, Sonali Kulkarni, Kishore Kadam

Directed by Umesh Vinayak Kulkarni

Rating: ***

Deool’s opening credits are striking and artistic, as though a pair of hands is carefully designing an alpana or rangoli with mud on the big screen. The film itself is just as considered: an insightful take on the commercialisation of faith and devotion, the commodification of God and how brutal market logic is transforming our rural idylls steadily and unalterably.

Set in the fictional village of Mangrul, Deeol (The Temple) begins by introducing us to the simpleton Kesha (Girish Kulkarni) searching for his cow Karde. A quick nap under the tree has Kesha seeing visions of the three-headed Lord Datta. The legend of the Lord’s visit to the village is enough to mobilise its residents into finding a new vocation. Forgetting the much-needed factory and hospital, they become stakeholders in running a profitable business venture—the temple of Datta.

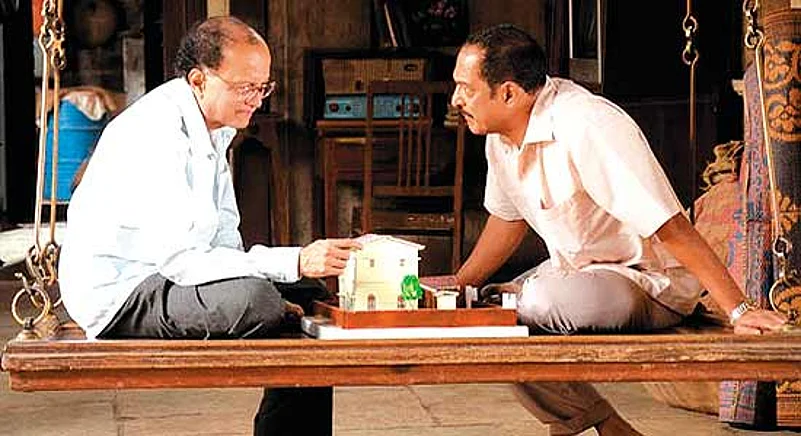

Director Umesh Kulkarni’s canvas is wide and ambitious. There are a lot of characters jostling for screen space, but he manages to make each a memorable stand-out. Nearly every persona is quirky, especially Bhau (Patekar), his teasing wife Sonali Kulkarni and the papad-making figurehead of a sarpanch. The only voices of sanity in the lost serenity are Kesha and the village elder Anna (Prabhawalkar), who believes that faith is something more personal than public. Alongside the debate on religion, there are none-too-gentle digs at the constant political games and media manoeuvres. There is also an interesting debate between the urban and the rural realities of India. Why should the rural be denied opportunities for modernity and development simply for the sake of remaining idyllic and unchanging?

The approach to story-telling in Umesh’s third feature is in tune with his first film Valu. Both are rooted in rural Maharashtra and employ satire, farce and folksy, rustic humour to make a point. However, unlike the more playful Valu, Deool makes a far stronger, scathing social commentary. Where it falters is in the uneven tone. There are moments when it hits you hard and others which leave you cold and disengaged. It’s when the allegorical, whimsical feel gets a tad too literal, and the bizarre lapses into the shrill and exaggerated. The TV soap-obsessed village women are pigeonholed and grating. No doubt the issue of money-making temples is an all-too-pervasive reality, but on screen, it comes across as being too straightforward and more obvious than ingenious, right down to that 3 Idiots-inspired bhajan. In contrast, the other verses, poetry and lyrics in the film reach out far more tersely and forcefully. As does the simple, unassuming, but deeply meaningful end. The innocence rests with Kesha alone, but even his immersion of the Lord Datta statue can’t keep the forces of corruption from breaching Mangrul’s gates