Even 50 days later, Anuj Kumar is still carrying the violence with him. The Dalit postgraduate student from Bihar says the assault has not receded into memory but lingers in his body, surfacing as fear and anxiety whenever he recalls what unfolded inside a men’s hostel at Hyderabad Central University.

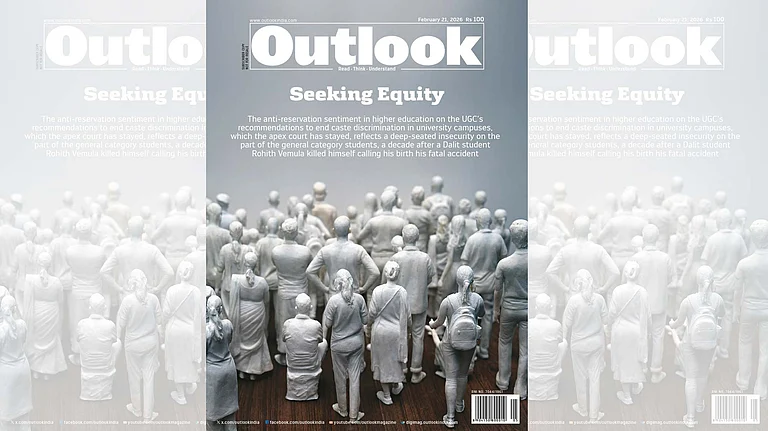

Seeking Equity: Caste Discrimination Continues At HCU 10 Years After Rohith Vemula's Suicide

Without sustained political will Rohith Vemula’s legacy may remain symbolic rather than catalysing structural change in higher education

Kumar, who is pursuing a Master’s degree in sociology, says he was summoned to the hostel on December 11, 2025, by a batchmate from another department to ostensibly “settle an issue” that he believes was deliberately fabricated to target him. He and his friend Vinod Choudhury allege that they were then attacked by a group of students, beaten while being subjected to caste abuse. “We were abused for being Dalits, called creatures from ditches,” Kumar says. “They beat us while hurling caste abuses. We were abused for being Dalits, called ‘creatures from ditches.”’

The two students say they submitted written complaints to all the concerned authorities. “Fifty days have passed since the incident. Not only has no action been taken against the perpetrators, but one of the authorities is instead pressuring me to arrive at a compromise,” Kumar alleges.

While recounting the episode, he was visibly shaken, shivering with fear and anxiety. He was sitting at Velivada, the memorial site dedicated to Rohit Vemula, the research scholar who was driven to suicide in 2016 following what has been widely described as systematic discrimination within the same University.

Hyderabad Central University (HCU), one of the earliest campuses to nurture equity-oriented and anti-caste movements, observed the 10th death anniversary of Vemula on January 16. A decade after his death, Rohit’s life, struggles and the circumstances that led to his suicide continue to deeply resonate across the campus.

The memory day coincided with the promulgation of the University Grants Commission’s Equity in Higher Education Regulations, 2026, which triggered strong opposition from sections of students and faculty across the country. At HCU, student groups allege that the backlash was used by some to revive hostile narratives around Vemula.

“Institutions often fail to respond to students’ democratic aspirations. They also fail to internalise democratic values, which leads to issues of discrimination.”

According to student activists, a social media post opposing the UGC regulations carried derogatory remarks against Vemula. “An ABVP (Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad) functionary, while attacking the UGC regulations, made disparaging comments against Rohit,” says Dayanidhi Bag, a leader of the Ambedkar Students’ Union. “We have filed a complaint with the University’s Anti-Discrimination Committee against the student, Saket Pandey, an ABVP worker who posted these remarks on social media.”

“If you ask what has changed since Rohit Vemula, I would say not much, at least not in any significant way,” says Dr C.N. Rao of HCU’s Economics Department.

According to him the discourse around discrimination is far more pronounced now. “As a result,” he says, “the nature of discrimination has changed. It has become more subtle, more discreet and harder to name.”

“Institutions often fail to respond to students’ democratic aspirations. They also fail to internalise democratic values, which leads to persistent issues of discrimination,” says Dr K.Y. Ratnam of the varsity’s English department. Ratnam, who was arrested during the protests following Vemula’s death, says the crisis in universities is not just administrative but deeply political.

Many students that Outlook spoke to on the HCU campus described how the exercise of power and authority enables casteist practices to be deployed against students from marginalised communities. One recurring allegation was the misuse of interviews for research scholars’ admissions, which students say has been systematically used by casteist faculty members to deny entry to Dalit and other marginalised candidates.

Some academics and students feel there has been a pattern of policies working against Dalits, particularly in institutions of higher education, since 2014. “The Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship for SC and ST students was stopped. Earlier, the fellowship was available to all students admitted to PhD programmes,” says a faculty member. “When the government later reintroduced the scheme, the modalities were changed. Under the National Fellowship for Scheduled Castes (NFSC) and the National Fellowship for Scheduled Tribes (NFST), the eligibility criteria were altered and qualifying the NET was made mandatory.”

Sabari Girija Rajan, a PhD scholar, points to a pattern of discrimination in admissions. She says she was left puzzled by the sharp disparity between her written examination scores and interview marks. “I wrote entrance examinations at several universities, including JNU and other prominent central universities. I consistently did well in the written tests, but my interview marks were abysmally low. I still don’t know why,” she shares.

Students say this question was shared by many aspirants across departments. It prompted the Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA) in 2023 to launch an inquiry into whether systemic mechanisms were being used to sideline Dalit students. The association filed Right to Information (RTI) applications with multiple departments, seeking details of interview scores awarded during PhD admissions.

According to the ASA, the responses they received were startling. The RTI replies, the association says, revealed a pattern in which candidates from reserved categories were consistently awarded disproportionately low interview marks. The ASA alleges that this was done deliberately to prevent reserved-category students from qualifying in the general category and to confine them strictly within the reserved quota.

“The treatment meted out to Dalit students is systemic. One way to address this is through legal and regulatory mechanisms.”

In one department, the RTI data showed that four Scheduled Caste candidates received 0.3, 1, 2.1 and 8.4 marks respectively, out of a maximum of 30. In another instance, seven out of eight faculty members reportedly awarded zero marks to a Scheduled Caste student. Students allege that no candidate from the unreserved category was subjected to such extreme grading.

The RTI responses also showed that in the Department of Women’s Studies, a faculty member awarded zero marks to 14 out of the 18 PhD candidates who appeared for interviews, raising further questions about the transparency and fairness of the selection process.

After students made the RTI findings public, the University was compelled to modify the interview process, most notably by ensuring that a candidate’s caste identity was not disclosed during interviews.

“This has reduced visible discrimination, but some are now adopting more nuanced ways to target students from Dalit backgrounds,” several students say. One student describes the difficulty of securing a research supervisor. “Some professors strategically avoid taking Dalit students as scholars,” he notes, adding that he struggled for months to find a guide.

According to a professor at the University who spoke on condition of anonymity, the RTI disclosures and the reactions that followed have led to some changes in faculty behaviour, with professors becoming more cautious about practices that could openly be identified as casteist.

“The treatment meted out to Dalit students is systemic,” the professor says. “One way to address this is through legal and regulatory mechanisms. In that sense, the UGC’s recent move would have helped ensure justice against systemic violence and discrimination in higher education inst itutions. In many ways, everyday academic practices continue to reinforce discrimination, though now in more nuanced and less visible forms.”

In its interactions with faculty members across universities, Outlook found a striking pattern of self-censorship. Many professors were reluctant to speak on record, fearing retaliation from University authorities. “Please don’t quote me” was a common refrain, even from academics who have written extensively on caste and discrimination.

Several faculty members pointed to the period following Vemula’s death as a turning point. They said systemic repression intensified in the aftermath, with cases being filed against professors and activists associated with the protests. Many of these cases remain pending, awaiting trial.

“When you take up the issue of caste discrimination, and if your politics is anchored around it, then your life itself is at stake,” says a student leader. His warning is not merely rhetorical. It mirrors a pattern that several students and faculty members say has hardened on campuses after Vemula’s death. Sukanna Velpula’s life offers a stark illustration of what they describe as institutional retaliation against those identified with anti-caste politics.

Sukanna, who stood alongside Vemula in challenging caste discrimination at HCU, completed his PhD despite what he alleges were sustained administrative and academic hurdles. He later secured a postdoctoral position at IIT Bombay and published in internationally reputed journals, credentials that would ordinarily position a scholar competitively within the academic job market.

Yet, Sukanna says his academic record did not translate into employment. “I applied to at least 25 universities across the country. None of them called me for an interview,” he says. For him, this exclusion cannot be seen in isolation. “I don’t know why universities wouldn’t even call me for interviews,” he adds. “But I believe it is because of my anti-caste activities on campus.”

Students and faculty members believe that such outcomes reflect a broader post-Vemula pattern in which dissent and anti-caste assertion are not confronted openly but are instead met with silent professional exclusion. Formal punitive action may be rare, they say, but informal mechanisms such as stalled careers, closed networks and invisible blacklisting persist unabated.

“After years of waiting, I abandoned hopes of an academic career and returned to my hometown near Kurnool. Now I sustain myself through farming.” His journey, activists argue, underscores how the costs of challenging caste hierarchies in higher education extend far beyond campus, reshaping lives long after the protests end.

Not just Sukanna, according to activists, many of those who revolted against caste discrimination along with Vemula could not find regular jobs in academic institutions, despite being well qualified. Concerns are not limited to students alone. Several members of the faculty have also raised allegations of discrimination, claiming that their promotions have been delayed or withheld due to what they describe as the administration’s caste-blind approach.

One Associate Professor in a university in Telangana says he was forced to approach the SC Commission after being targeted by certain professors in his department. According to him, his promotion to Associate Professor, which was due in 2014, was granted only in 2022. As his promotion to Professor becomes due, he alleges that some colleagues are again working against him.

Academicians point to discrimination manifesting in multiple ways and demand stringent laws.

The Karnataka government has decided to introduce the Rohit Vemula Act, the Prevention of Exclusion or Injustice in Higher Education Bill, 2025, to address caste-based discrimination in public and private colleges. Yet, the personal accounts of students and teachers at higher educational institutions suggest that deeply entrenched caste prejudices cannot be dismantled by legislation alone.

Nearly a decade after Vemula’s death, Velivada remains both a memorial and a site of resistance on the HCU campus, underscoring a larger truth. Without sustained political will and broader societal support, Vemula’s legacy risks being reduced to symbolism rather than serving as a catalyst for structural change in higher education.

N.K. Bhoopesh is an assistant editor, reporting on South India with a focus on politics, developmental challenges, and stories rooted in social justice

This article appeared in Outlook's February 21 issue titled Seeking Equity which brought together ground reports, analysis and commentary to examine UGC’s recent equity rules and the claims of misuse raised by privileged groups.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)