The farmers’ protest march organised by the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) in Maharashtra has captured the nation’s attention and forced the state government to respond. Mobilising the farmers in this way required both a cause they could rally around and an impressive organisational feat on the part of AIKS.

The protestors’ core demands included the implementation of three initiatives: the loan waiver scheme, the recommendations of the National Commission on Farmers (Swaminathan Commission) and the Forest Rights Act (FRA). They also asked for fundamental changes to the river-linking project in order to save the villages of Palghar and Thane. None of these is unrealistic, nor are they outside the confines of the existing governance system; indeed, they show how an extra-parliamentary movement can negotiate with a government. However, the oft-repeated demand regarding the Swaminathan Commission deserves a critical enquiry.

The commission’s 2006 report was a comprehensive one that proposed the total revamping of the agricultural sector in the context of the huge number of farmers’ suicides in Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region. The report identified the following as key reasons for the farmers’ distress: poorly implemented land reform, water inadequate both in quality and quantity, technology fatigue, inadequate access to institutional credit, and limited opportunities for assuring and remunerative marketing. It also takes into account the impact of disasters on farming. There is nothing to criticise in any of these findings—Indian farming has indeed been enduring all these crises for a long time.

With the problems identified, the commission offered recommendations intended to help improve farmers’ access and control over basic resources, including land, water and bioresources, as well as credit and insurance, technology and knowledge management, and access to markets. No action has been taken to implement these recommendations since the report was submitted in 2006—and Indian agriculture has passed through multiple crises in the decade that followed. Farmers’ suicides have become almost a routine matter across the country, with about 12,000 such deaths in 2013 alone. Maharashtra tops the list,, followed by Karnataka, Telangana, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu; 87.5% of reported farmers’ suicides are from these states.

The government has managed to avoid taking responsibility for these deaths by shifting the blame onto the farmers themselves. The National Crime Records Bureau has started recording the root cause of farmers’ suicides in a complex manner, taking into account factors such as alcoholism, extramarital affairs and mental health issues—the structural issues have been set aside in favour of the personal. And the leaders of the long march were themselves very careful to avoid demanding any major structural reforms; they only asked for a minimum support system, loan waivers and the implementation of the FRA. Each of these is an ongoing scheme that has been delayed in Maharashtra.

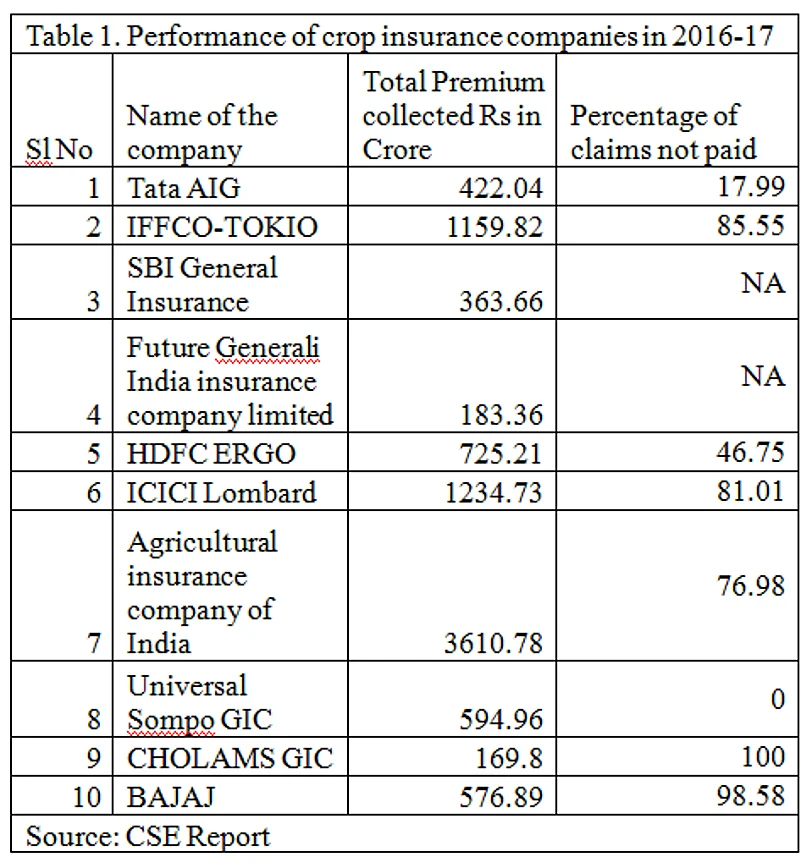

As for the Swaminathan Commission’s major recommendations, they hinge on major public investment in the agricultural sector—something that is decidedly not on the government’s agenda. The government has instead proposed various alternatives, the most important of which has been a crop insurance scheme that went against the farmers’ interests. As Table 1 shows, the only beneficiaries were companies, particularly private companies. Farmers in parts of Maharashtra afflicted by droughts and hailstorms are the worst affected by this massive privatisation—and yet the long march did nothing to address this issue.

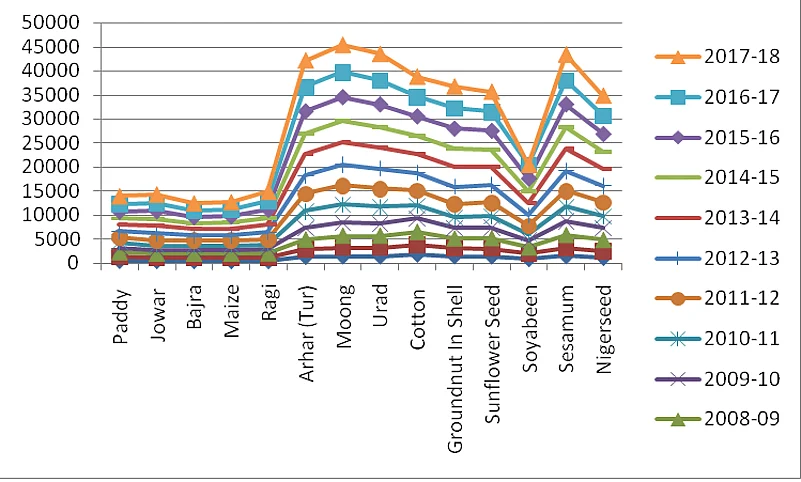

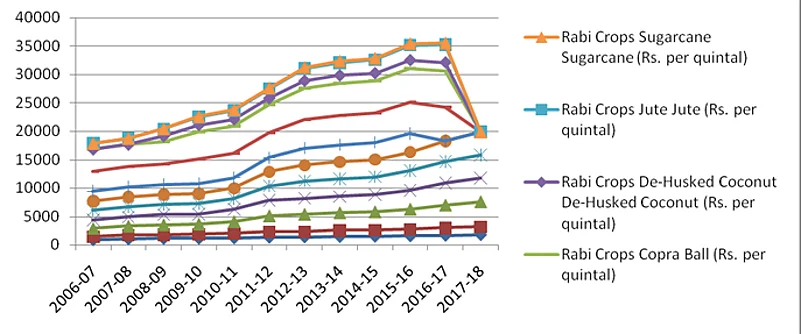

The government of Maharashtra has not fully accepted all the demands, avoiding decisions on certain core areas with promises to set up committees. It has agreed to implement the FRA and continue waiving loans because these are existing programmes. The Swaminathan Commission proposed a minimum support price that would be at least 50 per cent over and above the cost of production; this was not acceptable to the government—and instead of actually moving to implement it following the long march, it has merely set up a committee to consider the matter. It is also important to note that the minimum support price as calculated according to the current method fails to reflect the frequent fluctuations in the cost of production, and has failed to keep up with the latter. Figures 1 and 2 show how the minimum support price for various crops has only seen marginal increases year-on-year, which is not enough to match cost-push inflation. Thus, a more efficiently calculated support price that moves in lockstep with this inflation is required.

Source: EPWRF

Source: EPWRF

One other demand from the marchers was for a careful implementation of the national river linking project—without opposing the idea itself. This is in agreement with the spirit of the Swaminathan Commission report, which also mentioned that, “where large scale dislocation of families living in the areas which will be submerged as a result of the construction of large dams or linking of rivers is likely, the Gram Sabhas of the affected villages should be involved in the preparation of rehabilitation plans. This should be done at the time the large dam or other steps like the interlinking of rivers are on the drawing board’. Just like AIKS, the commission has no objection to river linking in itself, the likely environmental implications, farmland acquisition and the consequent displacements; it only states that collective involvement in the management of this displacement is desirable.

Interestingly, the leader of AIKS has denounced a local movement in Kannur, Kerala, opposing the acquisition of farmland for a highway project; he claimed that 56 of the 60 farmers affected had given their consent. He and the CPI(M) failed to mention that the owners of these farms are feudal landlords and are not involved in agriculture—they are only concerned with the value of the land, and not with the farms.

AIKS simply endorses such market-based suggestions without making an effort to study the issue from the farmers’ perspective. Meanwhile, the Swaminathan Commission’s recommendations are aimed towards rapid reform in the agricultural sector, which is not in the agenda of the political parties, and the report fails to take into account the environmental implications of such reforms. One can agree with the report’s technical aspects without considering it an infallible blueprint for the sector.

Thus, farmers should not limit themselves to the Swaminathan Commission’s technical views and should have an independent agenda in the ongoing struggle—otherwise, the crises they now face may continue to be insurmountable.

The author is an Assistant Professor at Jamsetji Tata School of Disaster Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences