Ahead of Kerala now getting its first Dalit priest in a temple administered by the state government, a famed British journalist with close India connections did write an account of similar struggles by a member of the Hindu downtrodden up north of the country.

Octogenarian Mark Tully’s latest book begins with a story about a ‘low-caste’ villager in Uttar Pradesh managing to overcome his meekness and win in his mission of building a shrine in his remote locality where Brahmins always wielded great influence.

‘The Battle for a Temple’ is the opening chapter in Tully’s 2017 work, Upcountry Tales:

Once Upon A Time In the Heart of India, which is a ‘part-fable, part-social documentary’, as Guardian columnist Ian Jack notes on the jacket of the 288-page publication by Speaking Tiger. The characters in all the seven stories of the book are from eastern UP, where three generations of Tully have lived earlier. All of those in the book belong to the common folk but “I won’t say the ordinary people”; instead, they don’t belong to the “prominent” citizens.

The book has its critical period attached to it. It portrays life in Purvanchal, as the pastoral Gangetic belt is known, in the second half of the 1980s—“a crossroad in Indian history” that the author prefers to call a “dead end”. For, that was when Rajiv Gandhi, as the prime minister, wanted the licence-permit raj to go, but “was not able to cope up with the resistance netas and babus put up” to reforms he attempted after taking over from his mother Indira Gandhi in 1984.

That way, aged Budh Ram’s initially-solitary bid to build a place of worship for his poet- icon Sant Ravi Das eventually succeeding is the victory that tacitly juxtaposes him favourably against the country’s most powerful person: the PM. The diminutive farm labourer in the interior Kosma could have easily given up given that his caste had seldom had any privilege nor a history of fighting against the privileged classes, but Budh Ram’s tenacity coupled with comical providence enables him to emerge as a hero of both the community and the region with a feudal hangover.

In fact, so timid is Budh Ram that he isn’t really sure to attend a village meet that is scheduled to discuss his proposal on building the temple. He somehow musters courage to attend what is called a biradari, where the protagonist “took the chair next to the pradhan but overcome with nervousness and fear he couldn’t speak”. What’s more, a burly middle-aged man called Kamal scorns at the poor man, warning the audience how the Gosains (Brahmins) “will never let it happen.”

Yet, Budh Ram musters the courage to speak about the greatness of the 15th-16th- century bhakti philosopher “who told me God is within us and equal in all” besides that “the nine doors of the senses prevent us from finding God within us and coming to moksha…” To the surprise of his listeners, including the village pradhan Ram Prasad, the doddering man speaks in near-trance—much like the Jewish barber hero in Charlie Chaplin’s 1940 American film The Great Dictator. Only that, here Budh Ram has only begun his fight.

The crowd, nonetheless, gets enthused. Optimism sets in among the Dalits, who make the initial moves for the temple construction. This invites the ire of the Brahmins, who come as a pack to the site meant for consecration and manage to dent the confidence of the lowly Bhangis. The local police station officer plays tricks on the Dalits. Ostensibly being bribed by the Brahmins, he fools the temple builders; worse, he begins to increasingly intimidate them.

Almost having given up, Budh Ram, along with the pradhan, makes a hesitant appearance before the local legislator. Sanjeev Rai, the MLA, straightaway dismisses them, but the politician’s shrewd right-hand man Sanjay Gupta intervenes, quickly convincing the leader the vitality of the majority Dalits as a vote-bank. That works, and the MLA loses no time in showing the SHO his place. The unexpected manipulation mellows the Gosains, too, at the end of which a “shining white temple now stands in that grove beside the river.” Budh Ram, the story concludes, doesn’t give himself any credit, all that goes to Sant Ravi Das.

This book by 81-year- old Tully, a Calcutta-born former BBC bureau chief, of “unlikely rebels”, as the jacket puts it, “finding ways to deal with bad governance, corruption and social hierarchies”. Besides Budh Ram, it tells similar stories about how a “clear-headed, clever farmer’s wife saves her family from her husband’s follies, a former headmistress leads the battle to save an endangered railway line, a politician’s son learns what it means ‘to eat the dust of UP’, a peaceable, comfort-loving policeman defies political pressure to solve a murder, an agnostic becomes a monk.”

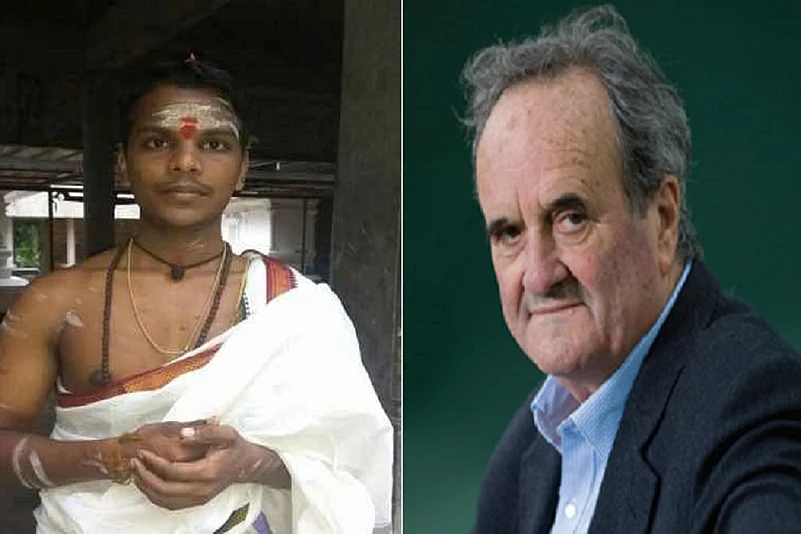

As for Kerala today, a good three decades after the exit of Rajiv Gandhi in power at the Centre and a communist regime ruling God’s Own Country, the state-administered Travancore Devaswom Board’s historic move saw 22-year- old Yadhu Krishnan assuming duties at the sanctum sanctorum of a vintage Shiva temple in central Travancore. A native of Koratty in Thrissur district, Yadhu—an alumnus of Sree

Gurudeva Vaidika Tantra Vidyapeethom in Paravur north of Kochi—is one of the six Dalits and 36 non-Brahmins recently recruited by the 1950-founded Devaswom Board that currently administers over 1,200 temples.