Framed by the narrow slit in her veil, ShehzadaBatloo’s eyes were level and strong. If there had been tears there for the sonshe had lost to police bullets, they had long ago dried. "I think allmothers should feel proud if their sons are martyred", Shehzada Batloolater said of her teenage son Samir Batloo, who was shot after the mob he stoodwith charged a Police post in Srinagar’s Fateh Kadal area. "I believe myson will vouch for me in the hereafter", she continued, "and I will berewarded with an abode in paradise".

Across the Pir Panjal mountains in Jammu, Kuldip Kumar Dogra dramaticallycommitted suicide at the end of a speech in which he demanded land for Hindupilgrims at Amarnath. Hindutva leaders held out Dogra’s death as a model foremulation -- and their audiences responded. Protestors have proved willing notjust to die but to kill.

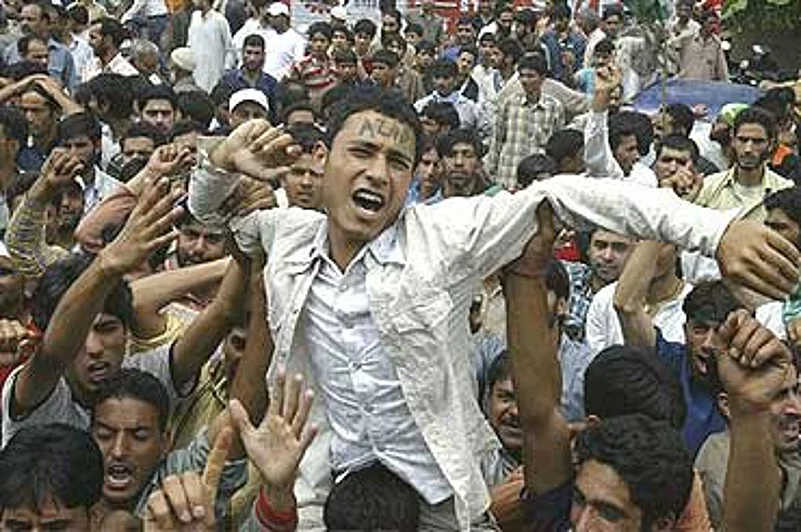

Ever since the Shrine Board protests broke out in June, a cult of death hasflourished in both Kashmir and Jammu, as both Islamists and Hindutva groups haveengaged in what they represent as a war for civilizational survival. In bothKashmir and Jammu, the soldiers of this war -- mobs numbering tens of thousands-- have swept the state before them.

On the morning of August 15, India’s Independence Day, Police personnelhoisted the national flag on the Clock Tower at Srinagar’s historic Lal Chowk-- a ritual that had continued uninterrupted through the long jihad. Less thantwo hours after the flag went up, though, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF)personnel at Lal Chowk were told an Islamist-led mob was marching there,intending to hoist Pakistan’s flag on the tower. With strict orders not tofire, the CRPF pulled down the Indian flag rather than allow it to be rippedapart by the protestors. Elsewhere in the city, Islamist leaders like AsiyaAndrabi were doing just that.

India’s strategy -- if it can be described as one -- in essence appears to beone of retreat. Ever since the Police opened fire on protestors seeking to marchacross the Line of Control (LoC) to Muzaffarabad, leading to street battleswhich led to the loss of at least twenty lives, the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K)government has withdrawn from confrontation. Large parts of historic Srinagarare in the de-facto control of Islamist groups, with Police and CRPF personnelholding a handful of fortified pickets at major street corners.

Perhaps the most spectacular demonstration of just how far the state’sretreat has gone became evident on August 18, after the J&K governmentallowed Islamists to stage a massive pro-Pakistan protest in the heart ofSrinagar -- ignoring warnings from India’s intelligence services that thedecision could lead to a meltdown of state authority. Led by theTehreek-i-Hurriyat’s (TiH) Syed Ali Shah Geelani and the All Party HurriyatConference’s (APHC’s) Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, at the time of writing, tens ofthousands of protestors assembled at Tourist Reception Centre in anunprecedented show of strength, even as Police were ordered off the streets toavoid confrontation.

Srinagar district Commissioner K. Afsandyar Khan and Senior Superintendent ofPolice S.A. Mujitaba were earlier despatched to stage negotiations on themanagement of the scheduled protests with Geelani -- a de-facto acknowledgmentthat the Islamist leader has emerged as an alternate source of administrativeauthority. Their request for the protest to be scaled down was rejected by theIslamist leader. Governor N.N. Vohra and his advisors then orderedDirector-General of Police Kuldeep Khoda to move his forces out of centralSrinagar, to avoid clashes with protestors.

In essence, Governor Vohra’s strategy rests on assurances from Geelani andFarooq that the protests will remain peaceful. Advocates of thishands-off-the-mob approach note that similar assurances ensured a 100,000-plusgathering called to mourn the killing of Islamist leader Sheikh Aziz -- who wasfired on by the Police while attempting to march across the Line of Control (LoC),and thus became the first APHC leader to die of Indian, rather than jihadist,bullet injuries -- remained peaceful.

Whether or not violence ensues, it is clear that the present strategy isleading to a large-scale erosion of state authority. Last week, Kulgam SeniorSuperintendent of Police, Imtiaz Mir, was reported to have been surrounded by amob and compelled to shout pro-Pakistan slogans. Elsewhere, the homes ofpro-India leaders of the National Conference (NC) and People’s DemocraticParty (PDP) have been torched; while leaders of anti-Islamist militia groupshave been attacked. Former state forests minister Qazi Afzal and his colleagueDilawar Mir -- both of whom supported the shrine board protests -- are amongthose who have been targeted.

Body of Tanveer Ahmed Handoo after he was shot during a protest in Srinagar

But just what is it that drives this anger? Is itresentment against India -- or something more primordial? For answers, we canturn usefully to history.

"There is no Hindu or Muslim question in Kashmir", Sheikh MohammadAbdullah said in 1948, "we do not use such language". His words were,at best, a comforting fiction.

As Jammu and Kashmir moved towards independence, both Hindu and Islamicneo-fundamentalist movements acquired strength in the region. Communalskirmishes punctuated the course of the freedom movement. In 1931, after Dogratroops killed 28 protestors in Srinagar, Hindu-owned businesses and homes weretargeted. More communal violence broke out that September. Partition entrenchedthe communalisation. In Kashmir, Muslims watched the large-scale communalmassacres in Jammu with fear. Sheikh Abdullah later described how deeply theexperience had scarred his constituents. "There isn’t a single Muslim inKapurthala, Alwar or Bharatpur", Abdullah said, noting that "some ofthese had been Muslim-majority states." Hindus in Kashmir had their ownfears -- fears driven by Pakistani state support for tribes engaged in acampaign of communal cleansing.

Freedom ought to have meant the birth of democratic institutions which couldaddress these anxieties. Instead, elites in both Kashmir and Jammu acceleratedthe communalisation process. Navnita Chadha Behera, a scholar of regionalconflicts in J&K, has noted that the state’s constituent assembly secured"a clear concentration of powers in the valley through disproportionaterepresentation."

Kashmiri elites used their new power to redress the historic grievances oftheir region’s Muslims. However, they demonstrated little regard for competingclaims from Ladakh and Jammu. For example, the NC worked to give KashmiriMuslims greater representation in the state bureaucracy. However, theymarginalised Hindu Dogras, Muslim Gujjars, and Ladakh residents of bothreligions.

Five years after independence, the Praja Parishadlaunched an agitation against Sheikh Abdullah’s policies. Its leaders -- analliance of landlords and business elites angered by the redistribution of theirassets -- called for the abrogation of Article 370, the removal of Dograimperial laws that allowed only state subjects to purchase land and the fullapplication of the Indian Constitution . "Ek desh mein do vidhaan, donishaan do pradhaan nahin chalengey", went the Praja Parishad slogan:"one nation cannot have two constitutions, two flags and two PrimeMinisters".

Sheikh Abdullah used the rise of the Jana Sangh-linked Praja Parishad tostoke communal fears in Kashmir. In one speech, he claimed the Praja Parishadwas part of project to convert India "into a religious state wherein theinterests of Muslims will be jeopardised." If the people of Jammu wanted aseparate Dogra state, Sheikh Abdullah said, "I would say with fullauthority on behalf of the Kashmiris that they would not at all mind thisseparation." Sheikh Abdullah had, tragically, transformed himself from aspokesman for all the state’s peoples into a representative of KashmiriMuslims alone.

From 1977, the unresolved strains between Kashmir and Jammu becameincreasingly sharp. In order to fight off growing competition from theJamaat-e-Islami (JeI), Sheikh Abdullah began to cast himself as a defender ofthe rights of Muslims. He attacked the Jamaat’s alliance with the Janata Party"whose hands were still red with the blood of Muslims." NC leadersadministered oaths to their cadre on the Quran and a piece of rock salt -- apopular symbol of Pakistan. Abdullah’s lieutenant, Mirza Afzal Beg, promisedvoters he would open the Srinagar-Muzaffarabad road to traffic. It paid off: theNC was decimated in the Hindu-majority constituencies of Jammu, but won all 42seats in Kashmir.

When the 1983 elections came around, politicians learned from experience.Prime Minister Indira Gandhi conducted an incendiary campaign in Jammu, builtaround the claim that the discrimination the region faced was because it waspart of ‘Hindu India’. Across the Pir Panjal, Farooq Abdullah and his newfound ally Maulvi Mohammad Farooq -- secessionist leader Mirwaiz Umar Farooq’sfather -- let it be known that they were defending Kashmir’s Muslim identity.Matters went from bad to worse. At a March 1987 rally in Srinagar, Muslim UnitedFront (MUF) candidates, clad in the white robes of the pious, declared thatIslam could not survive under the authority of a secular state. MUF leadersbuilt their campaign around protesting the sale of liquor and against laws thatproscribed cow slaughter, which were cast as threats to the authentic Muslimcharacter of Kashmir.

Jammu and Kashmir’s two-decade Islamist war sharpenedthe pace of communal polarisation within the state. Although Muslims in Kashmirwere the principal victims of a jihad fought in their name, few politicians inthe region proved willing to confront Islamists head on. Hindutva groups inJammu adroitly leveraged the situation to cast the conflict in the state as aHindu-Muslim contestation.

In both Jammu and Ladakh, the shrine war has strengthened forces who want thestate divided on religious lines -- a dramatic reversal of the situation in2002, where the Jammu State Morcha, which called for such a Partition, wasdecimated. Islamists in Kashmir, too, have made it clear they see Partition --and the incorporation of the Muslim-majority areas north of the Chenab riverinto Pakistan -- as the only way out of the crisis.

Partition plans for J&K aren’t new. In 1950, even as India and Pakistanwere still struggling to emerge from the communal holocaust which had claimedbetween half a million and a million lives, the United Nations-appointedmediator on J&K, Owen Dixon, suggested that a solution to conflict in thestate might lie in replicating the logic of Partition. Dixon’s plan was, atthe time, rejected in both India and Pakistan. However, the iniquitous structureof state politics gave it continued life. Former Sadr-i-Riyasat (StatePresident) Karan Singh was among those who put out variants of the proposal, onone occasion advocating the merger of Jammu into Himachal Pradesh, and turningKashmir into a separate Muslim-majority state. Secessionists like TiH chief SyedAli Shah Geelani and People’s Conference leader Sajjad Gani Lone; Hindutvagroups; and the Pakistani state have all propagated variants on this themesince.

In 1999, the NC itself issued a blueprint for Partition. Based on theproposals of a committee in which opposition groups, religious minorities andthe Jammu region were unrepresented, the state government advocated the creationof six new provinces. Muslim-majority districts Rajouri and Poonch were to becarved out from the Jammu region as a whole, and recast as a new Pir PanjalProvince. Udhampur’s single Muslim-majority tehsil, Mahore, was to form partof the Chenab province, while the rest of the district was incorporated intoJammu. Even the single districts of Buddhist-majority Leh and Muslim-majorityKargil, were to become separate provinces.

Later, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) threw its weight behind Hinduchauvinist groups in Jammu, who had revived the movement for the division ofJammu and Kashmir into three states, constructed along ethnic-religious lines.

Now, the project has ripened. In Kashmir, Islamists have argued that theviolence in Jammu -- amplified through the publication of fictitious accounts oflarge-scale killings of Muslims and the destruction of mosques -- is the trueface of India. Muslims, they claim, have no future. Hindus in Jammu, for theirpart, have been told that the expulsion of Kashmiri Pandits from the KashmirValley is a precursor to their eventual fate at the hands of the state’sMuslim leadership. Faked statistics have been used to claim that theMuslim-dominated J&K government denies Hindus representation.

Politicians in Kashmir and Jammu have done little totry and dam this rising tide of hate. Where Hindutva and Islamist groups haveheld dozens of protests, not one major political group has held peace rallies.No effort has been made, either, to build institutions that cut across socialfissures. Kashmir and Jammu have separate bar associations, chambers ofcommerce, professional guilds of doctors and engineers -- and even Pressassociations. For all practical purposes, residents of the two regions aresocial strangers, tied to each other by nothing but business -- and mutualhatred.

None of this ought to be a surprise for us. Islamists have long been workingto undermine the legitimacy of the secular-nationalist project in J&K -- andwith it, the keystones of the state’s incorporation in the Indian union.

In 2006, Islamists leveraged the uncovering of a prostitution racket in Srinagarto argue that secularism and modernity were instruments through which theIslamic cultural climate of Jammu and Kashmir was being undermined. Later, therape-murder of teenager Tabinda Gani was used to initiate a xenophobic campaignagainst the presence of non-ethnic Kashmiri workers in the state. Just as theshrine board protests in Kashmir were beginning in June this year, Geelaniasserted, "the state government, in collaboration with New Delhi, wants tosettle outsiders permanently in Kashmir to turn the Muslim majority into aminority." Soon after, the Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT) bombed a bus carryingmigrant workers -- a grim reminder of just what kind of nation Geelani hopeswill emerge from the struggle now underway in Kashmir.

Jammu, too, has seen a significant chauvinist mobilisation, feeding off theIslamist campaign in the north. Soon after the PDP-Congress alliance governmentcame to power, this new Hindutva leadership unleashed its first massmobilisations. Bajrang Dal, Shiv Sena and Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) leadersclaimed former Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Saeed’s calls fordemilitarisation and self-rule were existential threats. Pointing to theexpulsion of Pandits from Kashmir at the outset of the jihad, Hindutva leadersasserted that Saeed was preparing the ground for the expulsion of Hindus -- andHinduism -- from Jammu.

From 2003, Hindutva groups sought to forge these anxieties into a concretepolitical mobilisation around the issue of cow-slaughter. Hindutva cadre wouldoften interdict trucks carrying cattle, and then use their capture to stageprotests. It wasn’t as if the anti-cow-slaughter movement had stumbled on agreat secret. For decades, cow-owning farmers -- in the main Hindus themselves-- had been selling old livestock, which no longer earned them an income, totraders from Punjab and Rajasthan. In turn, the traders sold their herds tocattle traffickers on India’s eastern border, who fed the demand for beefamong the poor of Bangladesh. But Hindutva groups understood that the cow was apotent and politically profitable metaphor. Violence followed. In December 2007for example, VHP and Bajrang Dal cadre organised large-scale protests againstthe reported sacrificial slaughter of cows at the villages of Bali Charna, inthe Satwari area of Jammu, and Chilog, near Kathua district’s Bani town. Riotshad also taken place in the villages around Jammu’s Pargwal in March 2005after Hindutva activists made bizarre claims that a cow had been raped.

In 1947, Mahatma Gandhi had seen in Kashmir "a ray of hope in thedarkness", as communal harmony held against the tide of mutual carnage thatwas afflicting other parts of the country. Today, in the midst of anapparently-permanent eclipse, J&K desperately needs leaders who can pointits people in a direction where they might, once again, discover a glimmer ofhope.

Praveen Swami is Associate Editor, The Hindu. Courtesy, the SouthAsia Intelligence Review of the South Asia Terrorism Portal.