Everywhere A Doosra

1993 Wasim Akram loses his captaincy for allegedly offering fast bowler Ata-ur-Rahman Rs 1 lakh to under-perform against New Zealand.

1998 Shane Warne and Mark Waugh accuse then Pakistan captain Salim Malik of attempting to bribe them to lose matches. After an inquiry by Justice Qayyum, Malik and fast bowler Ata-ur-Rehman are banned; doubts raised over Wasim Akram, Inzamam-ul-Haq and Mushtaq Ahmed too.

2002 A bomb explodes in front of a Karachi hotel where the New Zealand cricket team was staying. They call off the tour. Leads to Pakistan playing a 'home' series against Australia in Sri Lanka and Sharjah.

2003 Inzamam-ul-Haq and Younis Khan brawl in public while playing a game of warm-up football during the World Cup in Zimbabwe; Saeed Anwar tries to intervene but is shoved down to the ground by Inzamam.

2004 In May, Pakistan asks the International Cricket Council (ICC) for a code of conduct to prevent former cricketers from making match-fixing allegations without substantial evidence.

2006 Penalised for ball-tampering, Pakistan refuses to play in the evening session of the fourth Test against England at The Oval. The two umpires award the game to England, a first in international cricket's 129-year history.

- Mohammed Asif and Shoaib Akhtar test positive for an anabolic steroid, Nandrolone, before the Champions Trophy in India.

2007 Pakistan coach Bob Woolmer dies under mysterious circumstances during the World Cup in the West Indies, after a shock defeat to Ireland which knocks Pakistan out. The team is questioned.

- Rawalpindi Express Shoaib Akhtar claims he refused to accept a briefcase full of money to perform badly during a tour to India in 2007.

- Shoaib Akhtar hits Mohammed Asif with a bat during a dressing room spat at the T20 World Cup in South Africa, is sent back midway to Pakistan as punishment.

2008 Australia postpones tour of Pakistan citing security reasons. In August, the ICC postpones the Champions Trophy for 13 months after five of the eight teams refuse to send a team there. The tournament is shifted out. India, too, calls off its Pakistan tour. 2011 World Cup matches too taken from Pakistan.

- Dubai police detains Asif for possessing drugs. Earlier, he tests positive for a banned substance during IPL 2008.

2009 In March, gunmen attack the team bus of the touring Sri Lanka team in Lahore, injuring five players and fourth umpire Ahsan Raza. This sealed the prospects of Pakistan hosting international matches in the foreseeable future.

- In September, the National Assembly's standing committee on sports conducts a hearing on team's performance in ICC Champions Trophy after its chairman, Jamshed Dasti, says he has evidence the team underperformed deliberately in tournament. In September, Younis Khan resigns as team captain. Says he's "disgusted" by match-fixing allegations made against the team by a senior member of parliament.

2010 After Pakistan loses every match on its 2009-10 Australian tour, a PCB inquiry panel finds no evidence of match-fixing. But for “misconduct”, it bans Mohammed Yousuf and Younis Khan indefinitely; Shoaib Malik and Rana Naved-ul-Hasan for a year; and fines Shahid Afridi, Umar Akmal, Kamran Akmal

- In March, the NA’s standing committee on sports decides to scrutinise financial assets of cricketers in the wake of match-fixing allegations.

- Pak leg-spinner Danish Kaneria and Mervyn Westfield, both playing for Essex in English county cricket, are arrested in connection with an inquiry into spot-fixing.

- Afridi quits captaincy and Tests after the first Test match against Australia.

- Tabloid News of the World brings allegations that captain Salman Butt, Kamran Akmal, Mohammed Aamer and Mohammed Asif are involved in 'spot-fixing'.

***

As the rising water of the Indus swept away villages and marooned towns, inflicting ineffable suffering on a nation already reeling under daily attacks of suicide bombers, there were many who drew respite, even hope, from what could be called the 21st century equivalent of Noah’s ark: the glorious game of cricket. Thousands of miles away, on the greens of the United Kingdom, the Pakistan team was locked in a pulsating contest against Australia and then England. True, the wins were rare—just two in six Test matches—yet the nation found refuge from its unbearably harsh reality in the exploits of its fast bowlers. It was a sight to behold: 18-year-old Mohammed Aamer and Mohammed Asif tearing into their formidable opponents with some extraordinary pace and swing. It seemed Pakistan had rediscovered its fast bowling prowess of yore. Was this the beginning of a cricketing renaissance? The team became a beacon of hope for a nation drowning in abject sorrow, a poultice to the deep wounds of the present, a promise of what Pakistan still might be.

But it was too good to last. The proverbial Noah’s ark of hope sprang a leak even before it could sail at full mast. Pakistan, quite literally, became the news of the world—its fast bowling sensations, Aamer and Asif, were accused of bowling no-balls at premeditated points of the fourth Test match against England—which in turn was agreed upon between undercover journalists and ‘sports agent’ Mazhar Majeed. The latter has since been variously described as a realtor, friend of cricketers, but in reality he’s a spot- as well as match-fixer. Majeed was caught on tape saying he’d need to pay £4,000 each to captain Salman Butt (named the ringleader) and the quickies for bowling, arguably, the most controversial no-balls in the annals of cricket.

Green signals Match-fixer Mazhar Majeed accepting the £1,50,000 from an NOTW reporter

(Courtesy: www.notw.co.uk)

A beleaguered people seethed at the betrayal, at the battering of their hope, at their realisation that cricket, as every sport, can at best only be a metaphor for the nation playing it. Pakistan, today, is cricket’s graveyard, its players the hangmen of the game. But they have acquired such disrepute, such infamy, only because so many of Pakistan’s cherished values lie crushed, because its politics has become pathological.

People understood this instinctively and, for a change, reacted spontaneously, refusing to spin conspiracy theories. In Lahore, an angry mob pelted rotten tomatoes on donkeys named Asif, Aamer, Kamran (Akmal) and Salman. One of them said, “We are already facing so many problems...they took away our one source of joy.” One Wajahat commented on Facebook, “In 1999 you (the Pakistani cricket team) broke my heart. But I was 16, and I learnt to love you again. I fear I am too old to love you again.” A sarcastic SMS doing the rounds reads, “We, the flood-stricken people of Pakistan, salute the worthy members of our national cricket team for their daring move to collect huge donations for the flood victims, even through match-fixing.” Newspapers howled, TV channels bristled and commentators said cricket’s hangmen must be made to pay.

Political extremism was, anyway, strangulating cricket. Teams don’t tour Pakistan anymore because of security concerns. Some think Butt and the two As—Asif and Aamer—have done greater disservice to Pakistan than the terrorists who attacked the Lankan cricket team last year. Former spinner and ex-chief selector Iqbal Qasim sighs, “Pakistan cricket has seen every possible mishap, but this allegation of spot-fixing is one of the biggest. Let’s see how our cricket comes out of this one.” Adds former captain Imran Khan, “There is a need to send out a message to youngsters—crime does not pay. If, God forbid, the allegation turns out to be true, then it will be the biggest setback for Pakistan cricket and, probably, end the careers of the two best bowlers in the world.”

Butt snapped with Majeed and the NOTW reporter (Courtesy: www.notw.co.uk)

The possible loss of the two As could be the reason why the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) hasn’t shown alacrity in taking action against the spot-fixers. Its powerful chairman, Ijaz Butt, a close relative of defence minister Ahmad Mukhtar, says, “This is only an allegation. There’s still no charge or proof on that account. So, at this stage, no action will be taken.” Such legal hair-splitting seems incongruous against the coincidence of the two As bowling no-balls at the precise points of the fourth Test match as Majeed had promised. The guilty players, many here feel, should have been suspended pending exoneration from an inquiry committee. Perhaps setting aside that legal principle—innocent until proven guilty—would set a dangerous precedent in a country notorious for its corrupt leaders.

Or perhaps the PCB bosses feared prompt suspension could provide the basis for their own removal as well. Leading the clamour for their sacking is Iqbal Muhammad Ali, chairman of the Pakistani National Assembly’s standing committee on sports. He has threatened that his committee would resign if the government does not change the PCB management and recall the accused players.

A quick suspension may just about heal the hurt collective conscience. It isn’t likely to stamp out the illegal betting, nor deter or dissuade the players from taking the bookie’s bait for spot-fixing or match-fixing. The problem is systemic—it emanates from the cesspool that the PCB has become. The government replaces PCB officials on its whim and fancy; they, in turn, play favourites. Ex-PCB chairman Arif Abbasi even accuses board officials of being involved in the scam. He asks, “Why was Shoaib Malik taken back into the team despite his alleged involvement in match-fixing? Why do they keep bringing back the same corrupt, banned players over and over again?”

Perhaps it’s an exaggeration to implicate PCB officials but there’s no denying that they have in the past condoned guilty players or allowed them to get away with quite laughable punishment. Justice Malik Mohammad Qayyum, who headed a judicial inquiry into match-fixing 10 years ago, says, “Some of the players who I recommended should not be given any responsibility in team affairs are still associated with the team.” He is, of course, referring to the current coach Waqar Younis, whom the Qayyum committee had fined then, and fielding coach Ijaz Ahmed, who still has several cases of fraud pending against him.

Ass you like it Pak fans protest in Lahore after the scam breaks (Photograph by AP)

That the presence of senior players/managers who have a dubious past creates an atmosphere conducive for mischief is in no doubt. With what moral authority can they make players adhere to the prescribed norms? Like, for instance, Aamer was caught talking on a mobile phone in the dressing room during an Asia Cup match between Sri Lanka and Pakistan in Dambulla earlier this year. Mazhar Majeed was reported to be prowling around in town then too. Had the authorities taken exemplary action against Aamer then, he and Pakistan could have been saved from the current embarrassment. Similarly, Asif has been the enfant terrible of Pakistan cricket for long. The PCB simply lacked the will/ability to wean him away from the path of destruction.

Former captain Rameez Raja alluded to this vitiated atmosphere while analysing Aamer’s career. “Aamer comes from a humble background,” Ramiz said. “He is 18, with an impressionable mind, and if he has been keeping bad company, it’s possible he could have been drawn (into wrongdoing). But if that’s the case, then the guys who got him in should be put behind bars because they’ve spoilt a grand career. They’ve infiltrated and spoilt a young mind...it’s a shocking state of affairs.”

The “humble background” argument has also been invoked to explain the match-fixing phenomenon in Pakistan. It’s said that most Pakistani players, unlike in the past, now hail from impoverished backgrounds, which renders them susceptible to the lure of the lucre. Add to this the uncertainties of Pakistan cricket—there are no longer frequent matches, the competition is stiff, the selectors are known to play favourites. The players also earn far less in comparison to those from other countries and barely bag endorsements, perhaps a reflection of Pakistan’s economy. At times, extraneous circumstances, like India’s decision to disallow them from the IPL last year, also shatter expectations, leaving the players’ financial plans going haywire. For instance, it is said that Salman Butt had started to build a spiffy house on the expected earnings from the IPL, but had to borrow money to complete it. Could this then have prompted Salman to take the bookie’s bait?

The humble-background school of thought contends that circumstances drive certain players to maximise their earnings as quickly as possible, including by throwing away matches. Former PCB chairman Tauqir Zia is among those who agree with this logic. “Our cricketers come from humble backgrounds, they lack proper education and they think that their only chance to earn money is while they are playing. So they want to earn as much as they can,” he says.

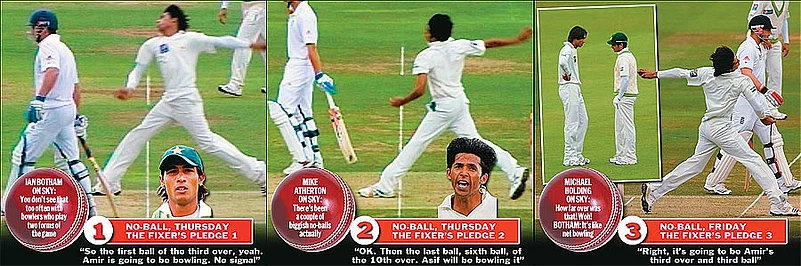

The three no-balls unfolding as promised by Majeed over the first two days of the Lord’s Test

Courtesy: www.notw.co.uk

But cricketers like Sarfaraz Nawaz scoff at such arguments, saying it’s absurd to compare a Pakistan cricketer’s salary with that of, say, an Australian. It’s more apt to compare his salary to that of an ordinary Pakistani. As he puts it, “As per the standard scale of salaries in Pakistan, the earnings of cricketers have made their lives into rags-to-riches stories. They receive far better salaries than those in other fields. These players have been conveniently let off every time they committed crimes.”

Zia links the menace to the changing values of Pakistani society. Greed has become a defining feature. “Our players are part of this society,” contends Zia. And spot-fixing has a particular allure because it is morally easy to justify—a no-ball appears an innocuous crime compared to, say, match-fixing. It seems a good bargain for thousands of dollars. “But the match-fixing web is vicious. Once you enter it, there’s no way out,” Zia adds.

Rashid Latif, former wicket-keeper and one of the first players to go public on match-fixing in the ’90s, believes it can’t be be stopped for it’s too pervasive now. And it’s impossible for those who haven’t played the game to figure out which episode in a match is fixed. “I have heard of bookies backing a certain player making sure that he does well in games by paying his opponents to fail, thus helping him become captain and getting him on their payroll.” Latif says the guilty players can be convicted only with irrefutable evidence. His suggestion—the icc should surreptitiously conduct a few dummy matches, conduct a sting operation of its own. Latif claims he suggested the idea to the icc in June ’03. “I said it would enable me to provide them with solid information regarding bookmakers in Dubai, Karachi and Mumbai. But they rejected it,” he says.

So then, what does Pakistan do? Well, the forecast looks grim but if cricket is indeed a metaphor for the nation, then the solution for Pakistan lies in rediscovering the innocence, the values it has lost in the past many years of venal, violent politics.