A Moveable Feast: Regional Cuisine Going Places

Bengali: Recently arrived at your friendly neighbourhood food joint: chingdi malaikari and hilsa paturi.

Chettinad: Gourmets and gourmands are galloping out in search of pallatur mutton masala and poondu meen kozhambu which originated from the mansions of Sivaganga and Pudukottai in Tamil Nadu.

Andhra and Hyderabadi: Gongura mutton, pessaratu dosas, the famed Hyderabadi kaache-ghosht-ki-biryani and shikampuri kababs anyone? Just dial for it.

Kerala: God’s Own Kitchens are bustling in your city, lacing the air with the inviting scent of ishtoos, appams and karimeen.

Avadhi: The kababs of aristocrats, from the kakori to the galauti, sell out at Delhi’s streets, at festivals in Mumbai and at fine dine restaurants.

Mangalorean: Spiced kane fish and gassi from Mangalore become must-haves for seafood worshippers.

Gujarati: Smoky undhiya, khandvi and dhoklas, methi theplas and khakhras—can’t churn them out fast enough to meet the all-India demand

Kashmiri: Gushtaba, yakhni and kahva—on the menu of top-end wedding caterers all over the country.

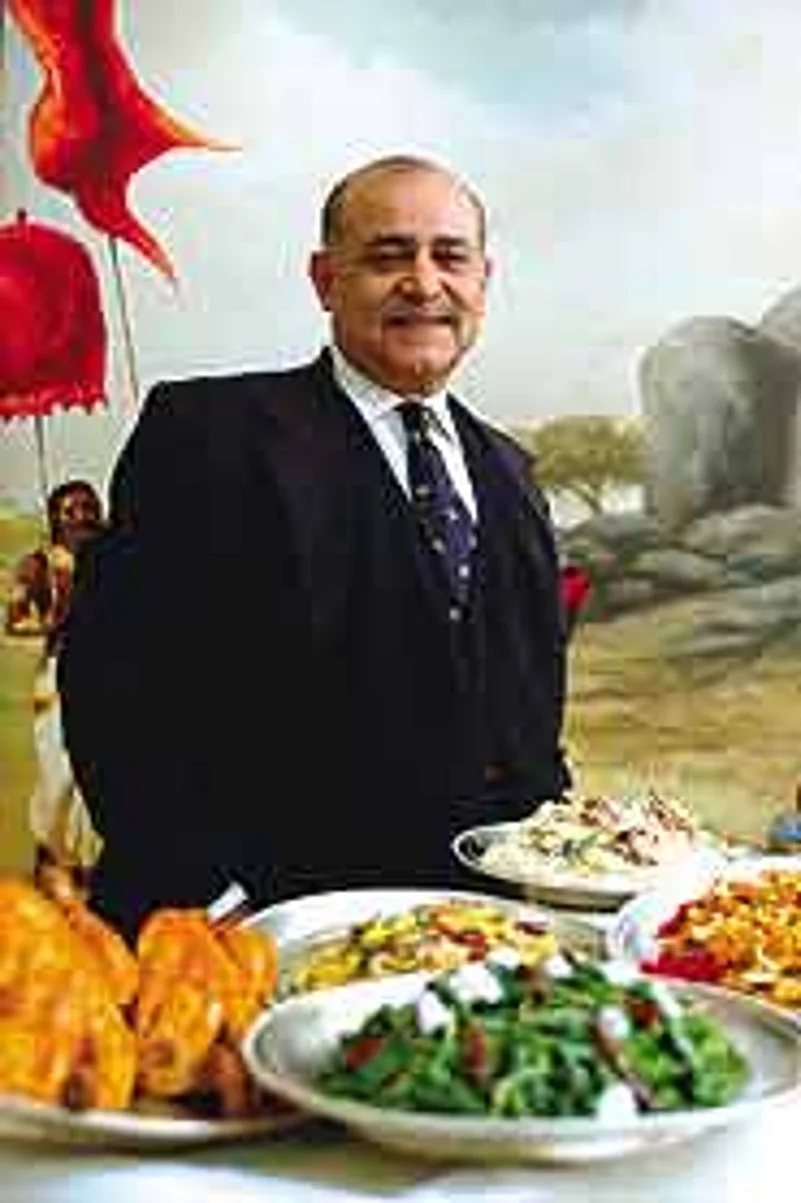

After an entire decade of simmering history in handis, when a few chefs carefully lifted the lids on a 300-dish banquet in Delhi in October, they were offering gastronomes a taste of the sumptuous unknown: the Dravidian dastarkhwan of Tipu Sultan. A 1,000-recipe repertoire, which even the Tiger of Mysore barely tasted, having been at war for 18 of his 19 years on the throne. Almost 200 hundred years after Tipu Sultan died while defending Srirangapatnam, his culinary legacy was reclaimed by the cuisine revival team at the ITC Welcomgroup in Delhi. "Our inspiration was the Sultanate-e-Khudadatti (a historical tome), which says the Mughlai dastarkhwan couldn't match that of Tipu," says Habib Rehman, executive director, hotels, travel and food, ITC Welcomgroup. His team of famed chefs and food consultants is credited with the revival of several lost cuisines.

With the community-based cuisines that influenced Tipu's repast now locked into separate states, like those of the Bunts and Tulus in Karnataka, the Moplahs and Syrian Christians of Kerala, and the Kongunadu people who live along the west coast, recipe-retrieval was backbreaking. The team, guided by historians and museologists in India, UK and France, studied and explored, and pleaded with grandmothers, priests and community cooks for ingredients and recipes. Slowly they divined Tipu's secular daawat—the gosht rikabdar pulao (tender lamb shanks with rice) that echoed his Muslim lineage, kadhambam (a mellow vegetable and rice porridge) from the Sri Ranganatha Temple in Srirangapatnam, where priests cooked this prasadam undisturbed during Tipu's reign. And even soppu pallaya, spinach with coconut milk, made like the classic French epinard a la creme, a taste young Tipu might have developed when learning military tactics from French officers employed by his father, Hyder Ali. Mapping Tipu Sultan's territory, recipe by recipe, this banquet menu documents a living culinary trail to the valiant Tiger of Mysore. It's also another tribute to Indian food, which Rehman considers 'the mother of all cuisines.'

As India witnesses the rise of regional platters, our broadband dining categories, of Mughlai and Madrasi, are fast blurring. Today, more than ever, there's a steaming exchange of cuisines criss-crossing state borders, and foodies are savouring the barter. Like at the recently-opened Amritsari Rang in Delhi, where, almost 60 years after Partition when Punjabi refugees poured into the capital, diners are getting their first taste of Amritsar's rich flaky stuffed kulchas, bhatti-da-murg and saffron-laced lassi. This former Italian restaurant now gets its daily supply of fish, vadiya and papads from the Golden Temple town. In Calcutta, the upscale eatery Tamarind is serving up Andhra food and has chefs coming round to describe the fiery-hot character of Guntur chillies. Chennai is seeing an exponential growth of Kerala food. The Kumarakom restaurant, which serves affordable Syrian Christian cuisine, has expanded to six branches, while new restaurants have sub-specialised into Malabar Muslim and other Kerala food. And in Bangalore, novelty Mudaliar foods like chatti fish curry and mutton kheema vada from neighbouring Tamil Nadu are drawing in shoppers at the Garuda, Forum and Eva malls. In Kashmir too, you can easily grab a dosa by the Dal Lake in the summer.

Within homes, Sundays are for spoon-tours. The Matthews in Kochi don't always grind up coconuts for a meen moilee; sometimes they prefer a Kolhapuri mutton that can be mopped up with Maharashtrian ambolis (thick spongy dosas). Delhi-based mediaman Vinod Dua, a pucca Punjabi, and wife Chinna whose family comes from Tamil Nadu declare: "We're united by Kashmiri biryani." The Pants in Pune proudly display their pantry stocked with plump Goa sausages and aromatic Bohri Muslim curry powder. Exploring the myriad flavours of regional cuisines is now easy with major markets stocking up on everything from Kashmiri kahwa to frozen Kerala parotas. Gujarati khandvi and dhoklas are flying off the counters as are ready-to-eat packets of pongal, a rice kichri from Tamil Nadu made by mtr Foods—a brand even silver-haired ajjis in Mysore endorse for having converted authenticity into easy heat-and-eat sachets. Recently, Pakistan's famous Shaan masala brand was also selling Sindhi biryani masala and Hyderabadi pickle at the India International Trade Fair in Delhi. Internationally, celeb chefs like Ainsley Harriot are showing Londoners how to cook up a Parsi lamb dhansak and Maharashtrian shrikhand.

All around us, foodie nosh is getting elevated—from dosas to appams, koftas to gushtabas and sambhar to sol kadi. Regional identity has even been bestowed on our spices, after the Spice Board of India started proudly retailing pepper as the Tellicherry Garbled Extra Bold. Cookery book titles too reflect this yearning for the past. Dr Katy Dalal's bestselling Jamva Chaloji detailed popular Parsi recipes and now Jamva Chaloji II is packed with recipes for dying Parsi foods with a preface that reads, "make this at least once in your lifetime." Penguin Books India are remapping our appetite for 'cookery and culture' with their Essential Sindhi, Northeast and Kodava cookbook series highlighting non-restaurant cuisines; while Charmaine O'Brien's Recipes from an Urban Village delectably documents the intra-city cuisine of Delhi's Nizamuddin Basti.

"Regional cuisine revival is on in a big way, because we Indians don't take kindly to foreign foods, and are now rediscovering our wealth of zaika (taste)," asserts food historian Jiggs Kalra. Fellow food historian Pushpesh Pant explains the socio-cultural causes behind this plate-to-thali food return. He says, "In our haste to acquire a veneer of sophistication, we allowed systematic bombardment of our food. Now we're beyond that, that's why the rise of regional restaurants." A few months ago, he met a family who had driven 120 km from Meerut to Delhi, just for a Bengali dinner at the not-so-authentic eatery, Babu Moshai. "We've done the Chinese, Thai, Mexican, Pan-Asian and Mediterranean bit, now we're going sub-regional—not Punjabi but Amritsari, not Kerala but Moplah," says food critic Marryam H. Reshii. Migration within India and an increase in mixed marriages are also helping community cuisines to hop across state borders. Of course, the aviation boom or that Re 1 flight from Bangalore to Goa makes it easy to airdash from dosai at Mavalli Tiffin Rooms to vindaloo at Souza Lobo.

Our souls and stomachs have also been seduced by glossy lifestyle magazines and their appealing community food spreads, be it our sister publications Outlook Traveller or our Getaway Guides series. UpperCrust, which hit the stands seven years ago, is India's only dedicated food and wine magazine. Says its editor Farzana Contractor: "Everyone knows about Provence—we wanted to showcase our own flavour states. These features were a hit, right from our first issue, Daawat-e-Hyderabad. Our readers do visit khanavalis in Ratnagiri and papad shops in Amritsar recommended by us." There's also the rise of the tribe called foodies, born with an insatiable appetite for culinary adventures. But selective ecleticism still rules. We're okay with Saraswat Brahmin khottes, or idlis made in stitched jackfruit leaf cups, but not dohkhlieh, a Khasi speciality where a pig's head is skinned, deboned and stuffed with onions and herbs.

While celebrating this revival, it's also time to ask, why so late? Experts say that when hotel management institutes were set up to train chefs for 5-star properties, they needed to have a 24-hour coffee shop, and one continental, one French and one Indian restaurant. Regional food studies were ignored in this curriculum. To reverse this, at ITC-Welcomgroup hotels 2 per cent of the food outlay is reserved for cuisine research. After creating Bukhara, Dum Pukht and Dakshin—acclaimed restaurant brands that offer the broad flavours of north, central and south India, "Our mission now is to fill in regional niches," says Rehman. A few years ago, while researching Awadhi food, they traced an exquisite prawn biryani that couples Dum Pukht traditions and seafood. It was born when Wajid Ali Shah, the last nawab of Lucknow, spent his last years in Calcutta with his retinue of rikabdars (royal family cooks).

Bangalore-based restaurateur A.S. Kamat, of the Kamat Yatri Niwas, wants our westernised hotel management courses to adapt as demand for local food grows. He says: "Just as the government actively revived handlooms, they should do the same for local cuisines." Yet, in our country where food and languages change every 200 kilometres, our culinary infinity is almost as impossible to preserve as our crumbling monuments. India has a small pinch of food historians. And as Irani cafes with their bun-maskas and sali-boti are dying out, we don't have many communities like the Shettys and Kamats who've got hoteliering in their blood.

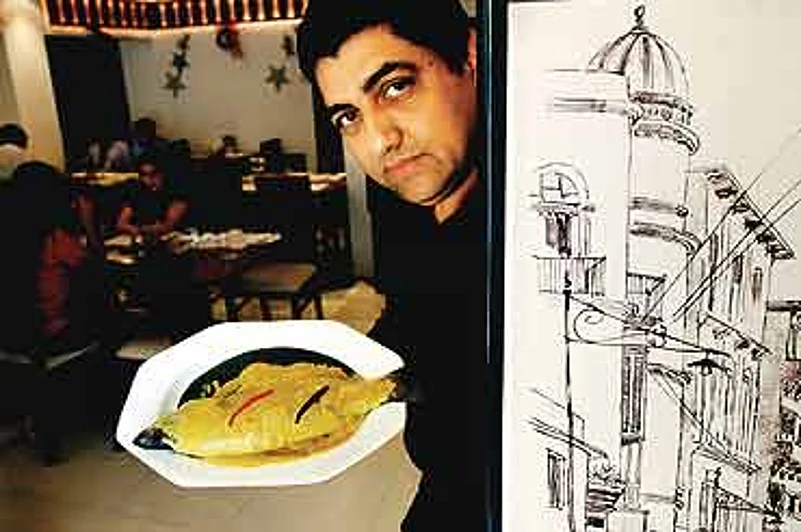

Today, even non-restaurateurs are taking up food as edible-shareable heritage. "We are a national-scale mission," declares Anjan Chatterjee, the foodie-adman behind the Oh! Calcutta chain, popular in Mumbai and Calcutta and all set for multi-city launches in Delhi, Bangalore, Pune and Chennai this year. This will be the third specialised Calcutta eatery to open in Delhi within one year, along with Chowringee set up by food critic Pallavi Thakur Bose that's just won a best restaurant award. Promising authenticity, which means high food costs, Anjan says, "We researched food from grandmother's diaries, old club menus, and found both the sweet, delicate ghoti food of West Bengal and the robust, onion-flecked hilsa paturi of Bangladesh." Today diners are plumping out on their chingdi malaikari, fish pardanashi and prawn pantheras. And the ratio of Bengali and non-Bengali clientele is about 50:50.

People are also awakening to the true local flavours of their own states. Gunjan Goela, a home-cook turned caterer in the capital, specialises in pure-veg 'purani Dilli ka khana'. Due to an intrigue factor, since 'few people know about this food', Gunjan says she's booked for parties throughout this wedding season, besides regular orders for mangochi chawal (mung dal pakodis in mung dal kadi with rice). In Mumbai, the 14-year-old Gajalee, a modestly priced coastal Maharashtrian fish eatery, has recently expanded to four outlets in the city, and a few more planned in Pune. Swati Snacks, an unsurpassable regional food destination, which has people queuing up for two hours even after expansion, is now planning another branch. In Chennai, food critic Marien Mathew asserts that "Chettinad food is the next big thing—in five years no one will talk of Tamil food as veggie fare." In Bangalore, Ganapathy Desai and Arvind Desai, owners of Unicorn and Fishland, are delighted by the quantum leap in demand for their coastal Karnataka foods, sparked off by Bangalore's boom and the return of nris who want home food.

"I want to return to my roots," asserts Syed Shervani who runs Rodeo, a bustling Mexican eatery in Delhi. He's alluding to his Allahabadi-Lucknowi heritage and marvels from his family kitchens like reshmi-ke-kofte (koftas steamed in silk). But unwillingness to compromise is causing delays. Says Shervani: "It's not easy transporting Awadhi food to Delhi, we can't use modern kitchens, we need open spaces and coal fires for our cooking." Sadly, conning remains rampant. Hotel Saravana Bhavan, a south Indian vegetarian chain, has started offering Gujarati food at some outlets in Chennai and in Delhi. "It's an insult to call it Gujarati thali, nothing works," cribs Chiman Patel, a software engineer new to Chennai who was trying to overcome his homesickness. In Delhi, as the velvety kakori kebab achieves diva status, Jiggs Kalra bellows: "I've met at least four Nawabs of Kakori." Besides, today's ingredients are a shadow of what they were—broiler chickens or oil-extracted garam masalas didn't exist when the Babarnama and Ain-i-Akbari detailed the Mughlai dastarkhwan.

Socio-political events have also had an appetising spinoff. Cosmopolitan Mumbaikars only heard the call for zunka-bhakar, a staple rural meal of bajra roti and spiced besan, when the Shiv Sena came to power. Says food columnist Vikram Doctor, "The rise of vada pao is linked with the Sena, they backed many stalls." Up north, after Kashmiri Pandits fled the Valley in the late '80s and resettled in camps and enclaves in Delhi, shops have begun stocking powdered saunf and saunth (dry ginger) masalas and var—a spice cake, essential for everyday Pandit food. Today, most butchers in Delhi can expertly cut mutton chaamps for tabakh maaz with a perfect fat-to-meat ratio.

Rohit Razdan, a Kashmiri Pandit, turned his back on a Chinese eatery in Delhi, and began catering to his community six years ago, both as a business and a service. He's got a monopoly on Kashmir Pandit weddings where compliments like "your yakhni took me back to the Valley" matter more than money. Today, without any advertising, the Razdan Saffron company has a 30 per cent non-Kashmiri clientele, which includes chef Ritu Dalmia who runs an Italian restaurant. Wazas—Muslim cooks from Kashmir whose heritage can be traced to Samarkand—have also set up shop in Delhi to promote their cuisine (a key difference in their cooking is that wazas spurn hing, Pandits shun garlic). Today, 25 years after setting up kitchens in the capital, Ahadsons, famed for their gushtaba, rishta and aab gosh, have an 80 per cent non-Kashmiri clientele. "We've also rediscovered recipes like chear kufth—apricot-stuffed meatballs, which we're popularising," says Ahadsons' Khan Mohammed Shafi.

Our search for health food is also helping fuel the revival of traditional regional dishes. The Kamat Yatri Niwas in Bangalore began as an Udipi eatery but switched to North Karnataka foods like jowar roti, brinjal masala and harvesoppu kootu (pulses mixed with harve, a local green) in 10 of their 19 outlets, to suit the people's health needs. Says Kamat, "Our small experiment is now a big enterprise." Similarly the Halli Mane eatery in Bangalore, which opened in 2002 to counter fast food chains, has won over eaters with their ragi-based thalis. At the Whole Foods health store in Delhi, "When new customers inquire about nachni, ragi and jowar, I tell them these are the grains we traditionally ate, not just wheat and rice," says clinical nutritionist Ishi Khosla, who's set up this health chain. Echoing this change, kulthi dal—the fortifying horsegram, once found stored in jars at Indus Valley sites in Daimabad (c 1800 BC)—had lost its place in our daily provision stores, but can now be easily bought at health stores.

And though we've lost our grandmothers' skills, our desire for her food hasn't diminished. Few of us can clean colocasia leaves, smother them in spicy-sour besan and evenly roll them into patrel, or pull off an intricate badaam ki jaali (almond lattice confection), but our taste for them lingers on. Moreover, our food was once intended for largish families, not singletons. Cooking a one-person biryani is impossible. It's much simpler to steam and have ready-to-eat biryani. This market is about Rs 80 crore and is expected to be worth Rs 250 crore in the next five years. Regional flavours are easy to savour with the Kitchens of India brand selling ready-to-eat Hyderabadi biryani, Chettinad chicken and Avadhi badam halwa in 50 Indian towns. This return to our roots is most evident in mtr's recent and popular ad that shows a child learning how to pronounce 'pu-li-yo-gare.'

But we're still only nibbling at our patriotism. Says Kalra, "My dream is that every kitchen in India should have not just garam masala, but also the panch phoron of Bengal, the bottle masala of the East Indians and the podis of Andhra." Restaurateurs and foodies, here's a hint. There's been an e-mail afloat in cyberspace, where sentimental Bengalis have listed foods they miss from Calcutta, like phulkopir shingara (cauliflower samosa), kosha mangsho (spicy meat) and patishapta (crepes filled with sweet coconut cream). Maybe it's time for the Pillais and Pathares to start off a nostalgia-chain mail, starting with shall we say, erisseri and puran poli? Maybe then, the way we ate will become the way we eat.

By Pramila N. Phatarphekar with Sugata Srinivasaraju in Bangalore, Jaideep Mazumdar in Calcutta, S. Anand in Chennai, Payal Kapadia in Mumbai