The republic entered the age of adolescence when we finally began our struggle with the post-Nehruvian loss of innocence.

The war with Pakistan and the cascading economic dislocation it brought; the unsatisfactory peace at Tashkent; a drought and food shortage; the devaluation of the rupee; the humiliating dependence on pl-480 wheat from the United States; and widespread unrest—all this combined to sour up the national elan.

All the certainties and certitudes of the Nehruvian era seemed unworkable. Or at least were contested rather vigorously. The old order, with all its pretensions to a copycat British civility and Brahminical gentleness, had become dysfunctional; the search for a new matrix of ideas and promises could hardly be postponed. And we were gloriously confused. Disparate forces, ideas and impulses were unleashed, and they kicked off an inevitable war over the direction and soul of the Indian polity. And all those who manned the institutions pushed the envelope.

The ball was set rolling by none other than the President of India. In his last address to the nation, on the eve of Republic Day, 1967, Dr S. Radhakrishnan, a very learned man, but deeply unhappy that he was not likely to get a second term, lamented the “widespread incompetence and the gross mismanagement of our resources”. And, a mere two days later, on January 27, J.R.D. Tata talked of a “mood of frustration and despair” and asked for the abolition of the Planning Commission.

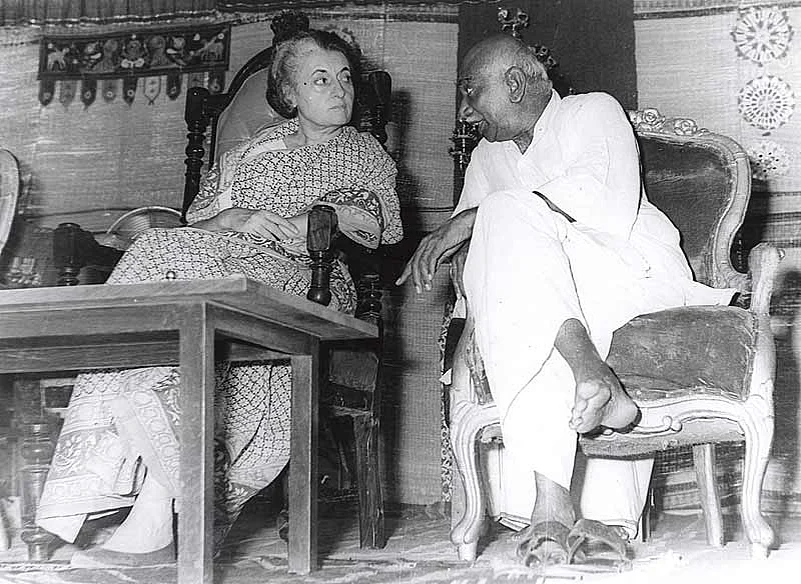

| After treatment for a nose broken by a stone -thrower in Orissa |

Post Nehru, the Congress was deeply enfeebled on account of a clash of ideas, egos and ambitions. The leadership had lost its capacity to accommodate new forces and new voices; not only that, it was no longer able to carry forward the Nehru-Patel tradition of disparate personalities staying together and working together in the interest of a larger purpose; the much-touted high command itself was divided, and this bad odour of factionalism at the top had seeped down to the state capitals. In state after state, important leaders—Vijayaraje Scindia in Madhya Pradesh, Mahamaya Prasad Sinha and the raja of Ramgarh in Bihar, Kumbharam Arya and the maharaja of Jhalawar in Rajasthan, Harekrushna Mahatab in Orissa, Ajoy Kumar Mukherjee in West Bengal—all of them walked out of the grand old party to set up separate shops and to provide respectability to the anti-Congress formations. And then, the voters did their own bit of ass-kicking. Powerful chief ministers like K.B. Sahay, P.C. Sen and M. Bhaktavatsalam and central ministers like C. Subramaniam were made to bite the dust. By the first week of March, it was clear that the voters in the fourth general elections had put an end to the 20-year-old Congress supremacy of the country’s political landscape.

And, of course, the loudest explosion took place in the Virudunagar constituency in what was then Madras state. An unknown 26-year-old student leader inflicted a humiliating defeat on the Congress president, K. Kamaraj, the great party boss who was serenaded as the very ideal embodiment of “old Congress values”. This explosion from Virudunagar was heard the loudest in New Delhi. The man who was hoping to be kingmaker found himself with a palpably diminished stature.

Its internal preoccupations had allowed the coming together of anti-Congress forces. The brilliant and bitter Ram Manohar Lohia had his revenge on his life-long betes noires, Nehru and his daughter, when almost all political formations, from the right to the left, came to subscribe to his thesis of anti-Congressism. His personal animosity towards Indira Gandhi got reworked into a very successful electoral strategy. By grafting intellectual respectability around anti-Congressism, Lohia made it possible for the communal, feudal, right-wing and regional parties to sup with the Communists and socialists in state after state. The parties of the Right Reaction—the Swatantra Party and the Bharatiya Jana Sangh—increased their tally in the Lok Sabha from 32 to 77, while the Communist score went up from 29 seats to 43.

Voters in two states, Madras and West Bengal, crossed a new threshold. Madras was angry with the Congress; the anger had begun with the anti-Hindi agitation and kept simmering. Suddenly, the magic touch abandoned the grand organisation, so vividly associated with the “great” Kamaraj. In 1967, two very unlikely political personalities—C.N. Annadurai and C. Rajagopalachari—joined hands to dislodge the Congress. The Congress was never to come back to power in Madras state, to be renamed Tamil Nadu in 1969.

It was also the beginning of a new era of populism: The DMK extravagantly promised that if voted to power, its government would give two measures of rice for a rupee. The state Congress leaders found the promise “an impossible proposition”. The DMK’s electoral success began the age of political paternalism. All Tamil political parties since have finessed the populist strategy.

Crossed, boxed Volunteers at a booth outside a polling station in Mumbai, 1967. (Photograph by Getty Images, From Outlook 05 November 2012)

Equally significant was the outcome of the West Bengal elections. On March 2, the first non-Congress government, the United Front, comprising the CPI(M), the CPI and the Bangla Congress, came to power, setting in motion an inevitable confrontation between the state government and the various CPI(M) dissidents, including Charu Mazumdar, Kanu Sanyal, and Jangal Santhal, who expressed their disagreements in a violent idiom at Naxalbari (in the Darjeeling district to the north of West Bengal). A similar ideological disagreement, though not coordinated, in Srikakulam, invited violent suppression. Inspired by Mao, various Naxal actions began their romantic experiment with different kinds of violence against “class enemies” in Calcutta. And rural Bengal witnessed the grand spectacle of a war on local landlords, involving guns, bows and arrows. It was only a matter of time before the state responded with its own coercion, setting in motion a “movement” that remains untamed till this day.

It was evident something was wrong, and something different would have to be done. An internal debate was on: whether the state had the capacity to be effective; and whether a realignment of political forces was in order to make it effective. Soon after the fourth general elections, the Congress undertook an analysis of its performance and came to decide on a ten-point programme which, in turn, became the basis of a great political struggle in and out of the Grand Old Party.

When the votes were counted, the Congress majority in the Lok Sabha stood drastically reduced. It was by no means certain that Indira Gandhi would get automatically re-elected as the leader of the Congress Parliamentary Party in the fourth Lok Sabha. Even though they had been humiliated at the polls, the party bosses were unprepared to let the young prime minister have her way. Indeed a great game was put in play: how to control Indira Gandhi. She had been saddled with Morarji Desai as deputy prime minister and finance minister. The deputy was soon complaining that “chhokri sunti nahin hai (the girl does not listen)”.

Word war An anti-Hindi protest in Madras

Just about the time the results of the fourth general elections were being collated, there was a little noticed judicial judgment that reignited a veritable ideological war over the soul of Indian democracy. On February 27, the Supreme Court, headed by Chief Justice K. Subba Rao, gave an unprecedented ruling in a case known as I.G. Golak Nath versus the State of Punjab. A divided bench ruled that Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution was not unqualified and it could not be used to curtail or restrict the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution. This decision, delivered by a deeply divided bench, was understood by all to be a triumph for the landed classes and other property interests. The bottomline of the Subba Rao judgement was that private property could not longer be appropriated for “public interest”. The court had nullified one of the most intoxicating axioms of socialistic rhetoric and welfare state practices. The progressive voices were mortified : “...the road to socialism (stands) barred”, pithily observed an editorial in Mainstream. On the other hand, this was a heady moment for the right-wing conservative voices and interests. C. Rajagopalachari, once Nehru’s comrade-in-arms and now an unforgiving foe of his daughter, crooned: “A great moral victory this decision of the Supreme Court has conferred on the Swatantra Party.”

After the Golak Nath judgement, and after the Swatantra Party formed a government in Orissa, the right wing was on a high. The feudal princes and maharajas had never had it so good in democratic India. Now, brilliantly guided by the formidable Rajagopalachari and Minoo Masani, they made a breathtaking move. In April, the republic was to elect a new president. Indira Gandhi had already ignored Kamaraj’s suggestion that Radhakrishnan get a second term (one more act of “defiance” on her part) and chose to elevate Vice-President Zakir Hussain to Rashtrapati Bhavan, thereby ensuring that the republic would get its first Muslim head.

Rajagopalachari, Annadurai. (Photograph by The HIndu)

Masani walked into Chief Justice K. Subba Rao’s residence and induced him to become the Opposition’s presidential candidate. The first great act of institutional impropriety was committed. It was the judiciary, that too its head, who committed the first grand solecism. What was worse, such was the confusion and such was the at-the-fork-in-the-road moment that this grave impropriety went largely unnoticed. No one had the courage to question that the head of the judiciary was getting involved in political games. This act of partisanship did not go unnoticed by the radical voices. The time to settle a score will come later. Justice Subba Rao’s partisanship had set the stage for a “committed judiciary” demand a few years later.

Towards the end of the year, one individual departure and one arrival came to matter. Ram Manohar Lohia passed away in October in Wellingdon Hospital; without his iconoclastic ideas and impulses, the anti-Congress camp got mired in its own unavoidable confusion. Second, Indira Gandhi decided to induct P.N. Haksar as principal secretary to the prime minister. The new man in the prime minister’s office was to quarterback an energetic centralisation of the Indian State’s resources, setting the stage for the 1969 Congress split, the 1971 electoral battle and the Emergency.

Khare, a senior journalist, has served as media advisor to PM Manmohan Singh