Conventional wisdom has it that policy changes that liberalised trade, industrial licensing and financial flows constituted the bedrock of the post-1991 reforms and yielded rich dividends in unleashing higher growth rates. This is despite the fact that successor reforms—the so-called second generation reforms rooted in core sectors such as power, agriculture, urban and higher education—have been stymied, with adverse implications for growth and distribution.

While this is true to a considerable extent, it draws attention away from an even more serious set of institutional reforms whose implications are profound not just for the economy but for India’s very future, namely the entire supply chain of law, order and justice. The upstream end of this chain is the structure and content of the tens of thousands of laws and statutes that govern any society; the next link is the investigative arms of the state, namely the police, followed by the prosecutorial arm. The courts and the judiciary and finally the penal system, the jails, make up the downstream end.

The entire chain, never very strong to begin with, has become deeply dysfunctional over the years. But if the deep malaise in India’s justice system is hardly a blinding insight, why is it that a problem so fundamental for the economy and society, and so well recognised, has not received the attention it deserves in reform debates?

Protests in Calcutta over the Left’s shame, the Nandigram killings, 2007

Many of the country’s laws are archaic, dating back to the colonial era. Even while the former coloniser has changed many of the original laws back home, the erstwhile colony has shown little inclination to do so despite profound changes in its society and economy. This might seem surprising, given how much activists and civil society seek a legal solution to virtually any serious issue. But this legal obsession is all about new laws and only rarely about repealing or modifying existing laws. In the late 1990s, the Jain Commission, in its Report of the Commission on Review of Administrative Laws, sought repeal of over 1,300 central laws while the National Law Commission too has been periodically giving recommendations for revision of laws. Yet, apart from a one-time repeal of 315 Amendment Acts in 2002, progress has been decidedly modest. When it comes to similar state laws, which run into many thousands and directly affect the day-to-day workings of business, there has not even been an inventory. The multiplicity and complexity of laws and administrative rules make compliance, deterrence and effective enforcement difficult and in many cases impossible. The result is circumvention by businesses while state functionaries harass and extract rents. While line ministries consequently have little incentive to reform these rules, law ministries in most states—and now even at the Centre—simply lack the capacity to do so.

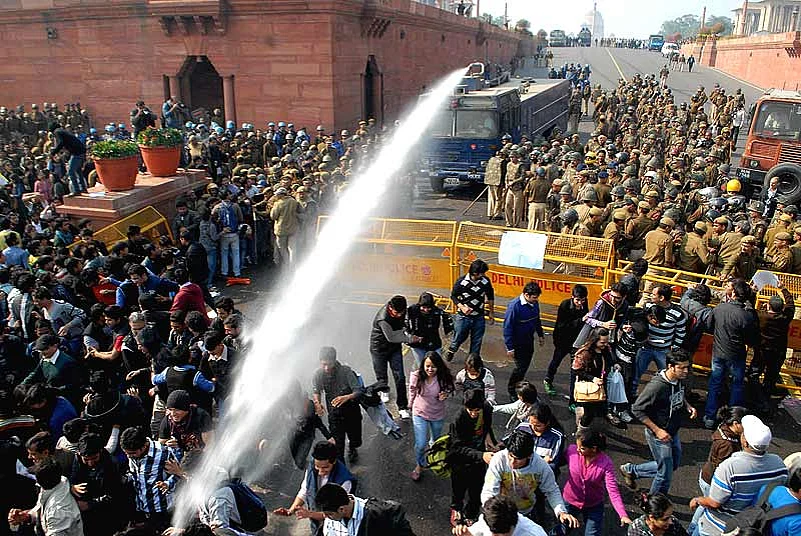

For most citizens, laws are invisible; their encounter with the justice system is foremost with the police, a venal and demoralised arm of the state, equally reviled and derided until it is most needed. There are some obvious reasons why the recommendations of numerous police commission reports—on autonomy, recruitment, equipment etc—carry dust. If there is one principle that unites the principals, politicians of all hues and stripes, it is that a competent, autonomous police force is a threat to their common interests. Societal pressure has also been limited. The rich know they have the financial wherewithal to ensure a compliant police force, so why bother? The middle class (and the rich, of course) have exited public services across a broad spectrum, and this is no different in the case of the police as evident by the huge growth in private security services and gated communities. The centrality of identity politics for India’s political and social movements has further weakened a common societal interest by making social representation in the police rather than its effectiveness their prime focus.

Good laws and competent investigative agencies can only go so far if the third link in the supply chain—the prosecutorial arm of the state—is weak. There is little doubt that in almost any case where the defendant has deep pockets—which means virtually all cases of import in the country—there is a major mismatch between the quality of legal counsel on the state’s behalf and the other side. Government lawyers are poorly briefed, often at the last minute, while a corporate or political defendant has a battery of highly paid lawyers who have had much more time and often competence to undercut the public prosecutor’s case, as attested in Bishwajit Bhattacharyya’s new book, My Experience with the Office of Additional Solicitor General of India.

India’s judiciary—the crucial third arm of the state—forms the bedrock of the legal system. The visible successes of the higher levels of the judiciary in driving prosecutions of the crony capitalism nexus in India masks the deeply troubling reality that for most ordinary people the judicial process itself has become the punishment. The extraordinary alacrity with which the courts grant adjournments has ensured that the powerful will always outlast the weak, making a mockery of what constitutes justice. The eagerness with which the judiciary takes on and intrudes on the space of the executive is in sharp contrast to the timid efforts to improve the effectiveness of courts for more basic tasks. The modest efforts in reforming the administrative organisation of the courts—from physical spaces to the smooth functioning of the courts qua organisations—have been outstripped by the sheer growth in case load. This has been magnified by determined government efforts to limit the hiring of judges, since a clogged legal system gives the powerful greater leeway. The legal profession itself needs reforms, whether the Bar Council of India which has conducted itself in a dreadful manner or even the cartel-like structure in the Senior Advocates of the Supreme Court which has ensured extraordinary rents for its members. And there is a real problem in the competence of judges, with many talented lawyers refusing to join the courts given the massive mismatch in the returns to legal talent in the public and private sectors. Debates on judicial reform have focused singularly on judicial appointments rather than on judicial capacity. Does India have sufficient courts and judges, given its population and the volume of litigation? Does the judiciary need better training and modes of recruitment? These are questions that are rarely asked, let alone addressed.

Delhi’s Tis Hazari courts sees over 55,000 litigants everyday. (Photograph by Sanjay Rawat)

But if with courts we at least have some sense of the dimensions of the problem, the last leg of the supply chain, India’s penal system—still primarily governed by the Prisons Act of 1894—is a black box. Stories of undertrials languishing for years without trial for minor crimes, custodial deaths and political strongmen leading comfortable lives and conducting business as usual, courtesy cooperative jailors, abound. When was the last time even the Indian media examined this issue?

The combined effects of these weaknesses are an alarming breakdown in the country’s justice system. To take a simple example: the low conviction rate of public officials (the cbi’s success rate is barely three per cent). India stands out in the degree to which witnesses turn ‘hostile’, often because of intimidation and bribery, because the law on perjury is toothless. All the court can do is initiate summary trial against the witness and sentence him to imprisonment for up to three months or a maximum fine of five hundred rupees! Even this is rare given the huge backlog of cases. Weak laws, when yoked to an even weaker enforcement system, virtually guarantee that the powerful will transgress without abandon.

It is now a well-worn cliche that India has law but not order; it also has laws but limited justice. Even if the rich and powerful ever get prosecuted, the fact that in the end with adjournments, appeals, witnesses turning ‘hostile’ because they have been paid off or simply dying of natural causes as cases drag on, the message is clear. Whether one engages in mass violence, or looting the treasury or natural resources, the important lesson is to do it in sufficient scale, provide oneself with a suitable political cover or political patronage and then brazen it out. The risks will be minor, indeed vanishingly small, compared to the upside gains.

It is ironic that India’s activists and civil society, for whom passing more laws and enshrining rights has become the principal instrument for progressive ends, have been largely silent in putting sustained pressure to improve the justice supply chain in the country. Most established democracies ensure that communal violence does not occur not by passing draconian legislation but rather by having an effective police, which is supposed to manage public violence no matter what the source or cause. But passing a communal harmony bill gets far more visibility for activists; working on administrative reforms in the justice supply chain is long, arduous and gives little opportunity to flex one’s self-righteous biceps. It is possible, of course, that when it comes to India’s justice system, Mao’s revolutionary adage, “There is chaos under the heavens—the situation is excellent”, might give reason for hope. Perhaps.

Devesh Kapur is director, Center for the Advanced Study of India, University of Pennsylvania. A PhD from Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School, he holds the Madan Sobti chair.