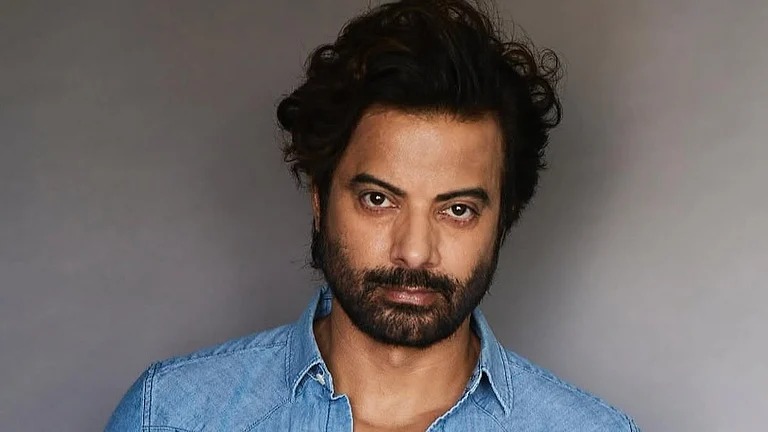

Last Monday TERI’s employees were asked to gather for an impromptu meeting at their Lodi Road headquarters in Delhi. R.K. Pachauri, the disgraced former director-general of the environment research outfit, had something to declare. As cups of chai and samosas were passed around, Pachauri announced that new director-general Ajay Mathur was finally taking over. Pachauri then revealed his own elevation as TERI’s executive vice-chairman, leaving his audience stumped.

One person familiar with what transpired says that Pachauri cracked a “sick joke” soon after his disclosures. Grinning, he told employees that TERI now has “two rookies at the top”—a rookie D-G and a rookie executive V-C—making many in the gathering wince, as they felt the joke was on them.

In fact, going by the headlines and outrage on social media, the joke is on all of us. A powerful man with serious criminal charges, including that of sexual harassment pending against him, has got sanction from one of India’s most respected environment research bodies. He has clawed his way back despite serious legal, moral, and corporate governance issues. Worse, the topmost executive position has been carved out by TERI’s governing council, packed with illustrious veterans of India Inc—Naina Lal Kidwai, Hemendra Kothari and Deepak Parekh—for the first time, especially for Pachauri.

For a while TERI’s women employees have suspected that Pachauri would, sooner or later, “get into trouble” for the way he treated women. In February 2015, a young woman (who quit in disgust in November) had levelled allegations of sexual harassment against him. This complainant expresses her shock at Pachauri’s elevation. “The council members are considered the who’s who of corporate India—and they could not take a stand,” she despairs in an interview (see box).

Pachauri’s new role is all the more damaging for TERI as its own internal complaints committee had confirmed this complainant’s allegations. As per the law, if this committee confirms sexual harassment charges, then it may recommend disciplinary action. TERI’s committee did recommend disciplinary action against Pachauri. “However, the governing council did no such thing. Instead it allowed him to go on voluntary leave and subsequently appointed him to the newly created post of executive vice-chairman,” says Indira Jaising, the senior advocate representing the complainant. In this way, Pachauri’s new role falls foul of the law.

The brazen way in which the TERI governing council has defended and protected the accused and victimised the victim shows their utter contempt for the law against sexual harassment at the workplace: “The man should be punished and the GC reconstituted,” says Brinda Karat, politburo member of the CPI(M). Kiran Mazumdar Shaw, who resigned from TERI’s GC over delays in the Pachauri case, was the sole member to do so. “Why is GC a bystander to this anomaly and accept RKP as V-C” (sic), she tweeted on January 26. All others have maintained a deafening silence. The pressure is building up. Not only is there a fresh allegation of sexual harassment against Pachauri, some students of TERI University—Pachauri is the chancellor—have refused to accept degrees from him. In response, Pachauri has merely “gone on leave”.

His lawyers insist, on their part, that the post of executive V-C is not new. “There has been in TERI a post of VP since inception. It was just lying vacant for a long time,” says Ashish Dixit, who represents Pachauri. He also says that the case has suffered from a kind of “one-sided” approach, especially in the media. “The internal committee did not recommend removal of Dr Pachauri. It only asked for compensation. So, even if upheld, Dr Pachauri would still not be removed from TERI,” says he. Dixit also argues that Pachauri’s new role is a “demotion”—and that he has “twelve orders passed by various courts”, none of which he has violated. “When trial hasn’t started, (and there’s) no chargesheet by police, how can people shout for his dismissal? He’s innocent until proved guilty,” says Dixit.

Fact is, there’s tremendous disquiet over the situation. Sections of Delhi’s elite are agitated, though they are unwilling to speak out. Some say Pachauri wants to hold on to executive powers because of perks. “A wider influence,” says one source, “comes to any person who is executive head of TERI.” This person is referring to the India Habitat Centre (IHC), a members-only convention centre housing TERI’s premises. As executive head of an institution located within these premises, Pachauri is entitled to be on its governing council.

IHC president Kiran Karnik confirms that the rules are such that a small number of organisations located within IHC are “permanently” on IHC’s governing council. To get a sense of the power that being on IHC’s top decision-making body entails, consider that when it opened 100 new memberships some years ago, 25,000 applied. Karnik says that memberships aren’t screened by the governing council. “Even if a governing council member recommends somebody, it must always go to the committee dedicated to examine fresh membership requests,” he says. Karnik is also on TERI’s advisory board. “For at least a year or year-and-a-half they [TERI] have not met to reconstitute this board—I don’t even remember being on it!” he says.

The same source informs us the NGO Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA) secured a membership at the IHC on Pachauri’s recommendation. Ramesh Gupta, Pachauri’s advocate, is on BBA’s board. When asked, he texted, “Not to my knowledge. However Dr Pachauri has no direct or indirect relationship with the BBA. I know Dr Pachori (sic) because of this case only”.

Undoubtedly here is an instance of a club of the powerful and influential. But what is still more shocking is how TERI’s eminent governing council, funded by the public, chose not to speak out for a woman fighting a lonely battle for the very basics—her own dignity and that of millions of women showing up at offices every day.