Wasting Away

- Over two years, 113 schemes saw no movement of money; Rs 1,700 crore lay unspent, in state government accounts.

- Some schemes seem outdated, like the ones for "fallen" animals, Indians touring France, an organ transplant scheme, the National Urban Health Mgmt scheme

- Only 5% of funds released for patient-care schemes in state hospitals in Madhya Pradesh have been utilised

- Maharashtra, Haryana ask for the new unique ID tracker scheme

***

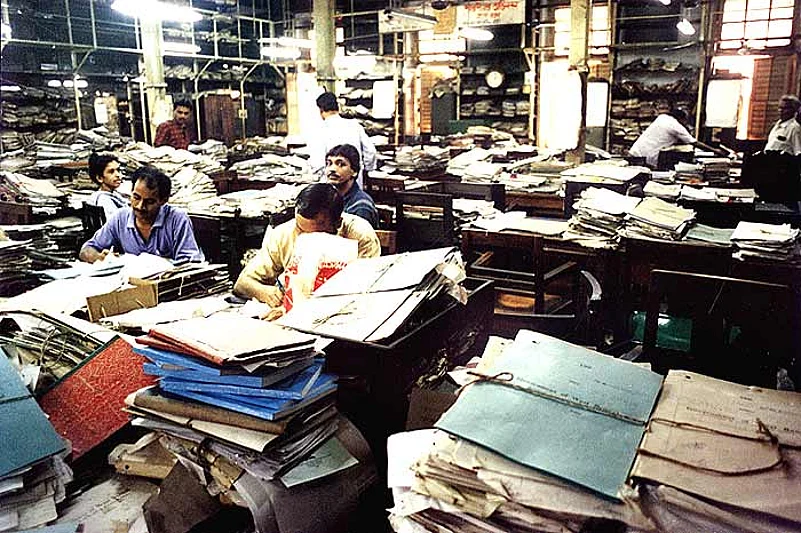

A favourite pastime of urban Indians is to guess how much of the money spent on ‘development projects’ actually reaches the poor. Some say that for every rupee allotted to the multi-thousand-crore schemes, only 1 paisa does its work. The more optimistic ratchet this up to 15, 16 or 17 paise per rupee. Truth is, nobody knows. Now under pressure from the spiralling protests against bad governance, inflation and corruption scams, attention is turning to how to plug the spectacular waste of money visible everywhere in India.

To detangle the complicated web of financial transactions—the annual budget for just the 900-odd schemes that New Delhi and states collaborate on is a mammoth Rs 1,85,000 crore—the government is planning to launch yet another scheme. The Planning Commission has recently given this new project an in-principle go-ahead, and the prime minister’s approval will be sought soon.

“The minute the Centre writes out a cheque releasing money to a state, it counts this as an expenditure. Yes, the releases are based on utilisation, but the money could be badly spent. Or the utilisation certificates can be delayed almost endlessly. With this kind of project, we identify who is responsible for the expenses...that’s our effort,” says Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman, Planning Commission, who reviewed the programme in August.

The idea is to give one lakh identified agencies—NGOs and state bodies—a unique 19-digit identity which will help track all their financial transactions, starting with central transfers and going up to panchayat beneficiaries. The condition is that the agency should be taking financial help from the Centre, or be paid for by a state. Their unique ID will soon be linked with the project headed by Nandan Nilekani at the Commission.

The project is being led by the central government, including the ministry of finance and the Planning Commission, and will be “strategically managed” by the National Informatics Centre. Officials will get online access as per need, from ministers to bureaucrats down to DMs, block-level officers and panchayat leaders. The aim is to make the information public, and available in real time.

So far, four states (Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab and Mizoram) have completed implementation. Here it’s possible to see details of how much money they were allotted by the Centre, when and to what agency the state transferred the money in turn, right down to the villages. What those agencies paid implementing agencies—the contractors, workers or individual beneficiaries of cash transfers (such as pensions or NREGA payments)—can also be accessed.

The project was recently tested and is ready to be rolled out in all states, though hitches remain. For one, cash payments have led to “disappearance” of funds in many places; funds through banks would have been a counter but access to them remains low across rural India. Project developers say they hope an RBI deadline of September ’11 to computerise all banks will speed up things. Of the 84 regional rural banks, only 44 are computerised, and fewer still of them are cooperative banks. Officials say the government will have to decide now if they want to continue using co-ops for payments.

The response from states has been encouraging. Bihar recently moved all bank accounts for agencies to the government sector. Haryana and Maharashtra have independently asked the project to be implemented. The home ministry has also sought their assistance in a bid to come to grips with expenses on “police reform” efforts.

Caregiver? Government hospital in Bhopal. (Photograph by Vivek Pateria)

Detractors say bank accounts and cash transfers, though presented as a panacea, don’t necessarily help, for nothing replaces careful monitoring of schemes, accountability and efficiency. Dr E.A.S. Sarma, an ex-bureaucrat and rights activist, says, “The demand for cash transfers is very low in states where the pds, for instance, is well-run. It’s the already inefficient states which favours cash transfers, because there’s little trust in the system.” He, however, supports the convergence of information about government schemes as “efficiency and transparency are always welcome”.

Getting banks to agree to reveal information on cash movements, in real time, was not easy—convincing them took a year. The result, however, is that agencies (such as an NGO) that have accessed funds from over one source for a single project can easily be “discovered”. “To combine public scrutiny with government accountability, the sources and routes of funds need to be transparent,” says an official connected with the project.

The project assumes that spvs, NGOs and government bodies, once given a unique ID, will lose much of their over-arching discretionary powers. It will be impossible for states to claim insufficient funds as the default source of their woes. “Mismanagement and errors may occur, but we want to eliminate chances that money will not reach beneficiaries because a babu has misused his/her discretionary powers. We’ll spot where the bottleneck is,” says Montek. He adds that he “will not oppose” making the information accessible to the general public, a process that can take two years.

Dr R.K. Thukral, who runs a series of online databases under the flagship Indiastat.com, confirms the lack of information on India and the vast interest in reliable (usually government) data: “I expect such a system to provide as vast an information bank as the RTI did,” he says.

While conducting the ‘pilot run’ in four states, the project unearthed many sources of mismanagement—and it wasn’t always outright fraud. At times, payments did not come through to individuals or contractors because the officials authorised to sign cheques were on leave. At other times, state authorities seemed to have forgotten about the resources at their disposal. In some districts, high-value cash transfers stood out among many smaller transactions. Either way, it’s going to be tougher to serve up those standard excuses for delay.