Mishaps At Indian Nuclear Plants

- 2001, Rajasthan: Turbine blade failures, cracks in end-shields, leaks in calandria, leak in many tubes in the moderator heat exchanger.

- 1999, Tarapur: Tube failures result in de-rating of the reactor.

- 1999, Madras: Four tonnes of heavy water leaks, exposing workers to radioactivity.

- 1994, Kaiga: The pre-stressed concrete dome collapses while under construction.

- 1993, Narora: Fire triggered by broken turbine blades leads to near-meltdown.

- 1992, Rajasthan: Fire in 4 out of 8 pumps threatens to affect cooling system.

- 1988, Madras: Heavy water leak exposes workers to radioactivity; plant shuts.

- 1980, Madras: Zircalloy pieces found in moderator pump after inlet cracks.

- 1976, Rajasthan: Reactors flooded due to construction errors.

***

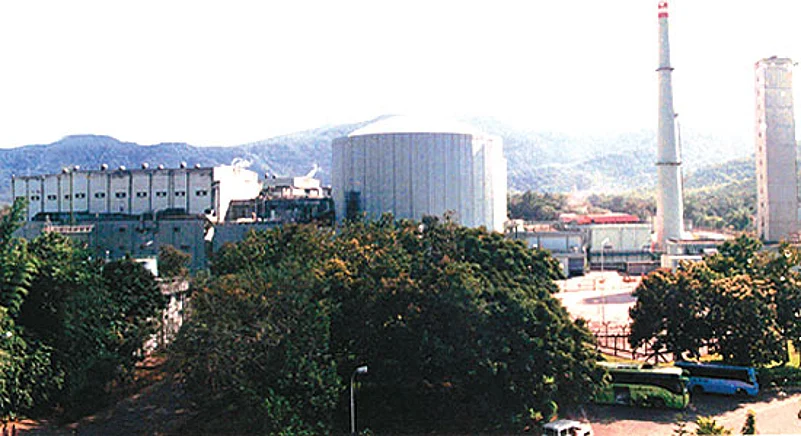

An eerie stillness envelops Kaiga and the human settlements in Kadra and Mallapur surrounding it which is nothing like the natural quiet of the Western Ghats. Ever since the Kaiga nuclear power station’s launch in 2000, people here have led uneasy lives, a constant, what-if fear of radiation lurking in the background. That said, seldom have they allowed their anxieties to be voiced.

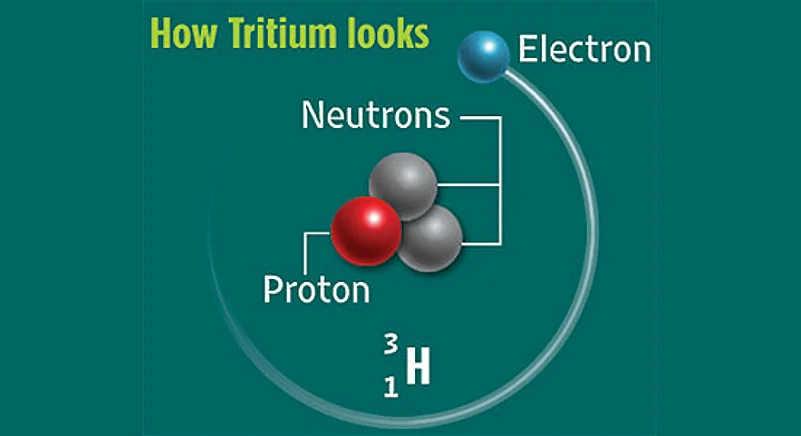

All that changed on November 24 when 50 workers (that’s the official figure) at the N-plant fell ill, exposed to radiation allegedly after they drank water “contaminated by tritium”, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, from a cooler in Unit I. Locals have looked more or less confounded since over the various theories of “sabotage” and “mischief” officials have been putting out.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has grandly declared there is “nothing to worry about the small matter of contamination”. The shroud of secrecy marking the official response, though, has done little to inspire confidence. The Nuclear Power Corporation, which runs the plants, has neither released the names of the workers affected nor revealed their exact medical condition. It has also not stated how many of those affected were NPCIL regulars and how many were contract labourers.

In fact, local authorities are doing everything to play down the issue. A formal complaint was lodged only on December 1, a good week after the incident. Inspector K. Kusumadhar of the Mallapur police station is at a loss to explain the delay. “The unit’s senior manager, Uma Maheshwar, filed a four-line complaint asking us to investigate. I have no idea if they have already conducted a preliminary internal inquiry,” he says.

According to details with the police, there are 1,647 regular employees at the Kaiga station, but no details on the numbers on contract. While some sources put it at around 2,000, others say the number may be higher. These daily-wagers, from across India, live in five major settlements adjoining the nuclear station—Gandhinagar Camp, Laxminagar Camp, Hartuga Camp, Tamil Camp and the Kadra Dam Rehabilitation Camp.

As outgoing Atomic Energy Commission chief Anil Kakodkar’s “deliberate sabotage” theory gains currency, the needle of suspicion is now being pointed at these labourers. But given the fact that many of them too have been exposed to the radiation, this looks like all-too-easy conjecture. Shamnath Vishwanath Naik, a member of the Kadra gram panchayat, where some of these contracted men live, says it’s “easy to find a scapegoat from among these people. No mystery related to Kaiga, whether murders or health hazards in the past, has been solved and this too will remain so,” he says dejectedly. Incidentally, there’s also talk of some intense inter-union rivalry—which earlier intelligence reports too had alluded to—but station director J.P. Gupta didn’t seem to think it a probable cause. Incredibly, there’s no CCTV coverage to fall back on either.

A radiation tag hangs from a tree in Balamane village, 3 km from Kaiga

How did it happen?

Outlook got in touch with a few contract labourers who drank the ‘radioactive water’. Anandu Mahabalesh Naik, 34, has been working in Unit I and II of the plant for the past eight years. He earns Rs 160 a day for eight hours of work. His primary job is to collect the special clothing used in the reactor building and elsewhere and send it to the laundry. When the reactor shuts down for maintenance, he also helps erect a scaffold around it after which others clean and paint it.

Currently, the Unit I reactor is shut for maintenance (closed on October 20) while Unit II is functioning. The two units are roughly 100 feet apart. Anandu says when he goes into the “dome” of Unit I, which has three doors, there is so much heat that his throat goes dry. So naturally, he consumes a lot of water the moment he’s out. Anandu was on the night shift on November 24 and drank about half-a-litre of water from the ‘contaminated’ cooler around midnight. Urine samples of plant workers are regularly sent for testing to the Health Physics Unit (HPU), which suddenly detected very high radiation levels in samples sent on November 24-25. That was how the contamination came to light.

Anandu says the water cooler is “always locked” and is opened only for cleaning. He doesn’t remember it being opened in the week preceding November 24. “If somebody has to put something into it, they have to open the nuts and bolts and that’s difficult given the security,” he says. Last year, says Anandu, a Bihari labourer was exposed to excessive radiation and was taken to Mumbai for treatment. In the last two days, he’s been having stomach and back pains, but is not sure if this is the result of the radiation. Interestingly, exposure to tritium radiation leaves no visible symptoms although its ingestion can increase the risk of cancer and can damage cells.

What about whole body counts?

Ramesh T. Nair (26), a contract labourer, is a supervisor in the two units, earning Rs 185 per day. He’s been working at the plant for seven years now and is far more articulate about his condition. He supervises the wall/floor painting and de-watering, and also keeps an inventory of the special gear worn in the reactor building like gloves, socks, shoes and the yellow uniforms. He was taken to the hospital on November 26 night and was administered saline water and given an injection. Radiation levels in his body showed 582 microcurie that day. A second test showed 862 microcurie (see info). (The maximum permissible amount of tritium in a litre of urine is 100 microcurie.)

Ramesh says the HPU wouldn’t give out the radiation count results earlier. It’s only after “the incident” and with the intervention of higher authorities that they started releasing it. “We weren’t allowed to speak to the doctor. For those of us with high radiation levels, they also conducted a ‘whole body count’ test, but they didn’t reveal the results,” he says.

Interestingly, on Sunday, November 29, station director J.P. Gupta had a lunch meeting with affected workers and their contractors. He is said to have thanked them for their “cooperation” and also for “keeping silent” about the issue outside. “None of our contractors spoke at the meeting, it was just us workers expressing a great deal of anxiety about their health,” says one of the men present.

About the water cooler, Ramesh says it’s kept against the wall and requires 2-3 people just to move it. There is a pipe for water overflow and a filter at the back of the cooler. And of the heavy water (said to have been put into the cooler), he says it can be collected only by the ‘operations group’ and nobody else can access it. “Contaminated water in the reactor is collected in the pits and goes out automatically. If somebody has to get down to the pits, they need permission from the HPU,” Ramesh says and adds that the water cooler was kept in Zone 2. There are four zones and Zone 4 is the closest to the reactor, and possibly with the highest radiation. “To enter the high radiation area, one has to wear the Ventilation Plastic suit,” he adds.

Shankara Gowda (28), who works as a mechanical helper in the first two Kaiga units, was taken to hospital by the staff on November 25. His urine sample is said to have been among the ones with the highest radiation count, 1,695 microcurie on November 25. The next day it was down to 642 microcurie. The variable counts have created severe doubts among workers about their overall safety.

Detecting Radiation Levels

Radiation count in urine sample is in microcurie per litre. Max permissible level is 100 microcurie per litre.

.jpg?w=801&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&dpr=1.0)

* Test results given out by HPU

***

Flush With It

What is Tritium?

Tritium is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. Produced in heavy water-moderated reactors.

Danger of consuming Tritium

Tritium is one of the least dangerous radionuclides. But exposure to it increases risk of cancer. Also damages cells.

Treatment

Tritium can be flushed out of the body by drinking fluids or by administering diuretics under medical supervision.

Amidst the panic, there is the curious case of 47-year-old Manohar Naik, who like Anandu sends clothes to the laundry and helps erect the scaffolding around the reactor. He says he drank water from the same water cooler on November 24 at 11.30 am, but his radiation count was so low he was neither alerted nor taken to the hospital. But he says he heard that a co-worker, Mutthana, had alarmingly high readings at 1,940 microcurie.

Manohar too says the cooler is difficult to open. “There are just two taps at the front and you have to put your mouth below it to drink water.” He also says that “the source of the water to the cooler is a tank outside...the tank is connected to the other coolers and canteen as well”.

Stitching together the bits and pieces of information from the affected labourers, it’d be safe to suggest the investigating authorities perhaps look beyond the ‘sabotage’ theories, and check if there is more to the incident than some “malevolent” elements trying to get even. Thousands of lives are at stake here, transparency and truth must prevail.