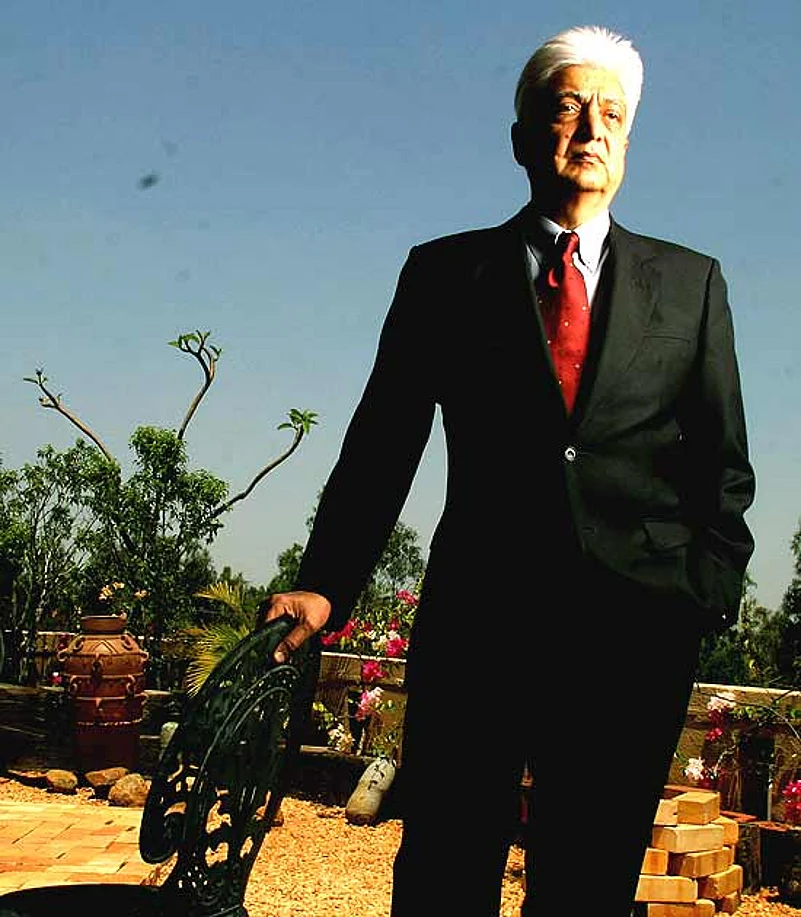

Life has a way of making its own plans for you. And—who knows—perhaps in the long run, the plans that life has are better than the ones you make for yourself. In 1962, at age 17, Azim Premji was studying at St Xavier’s, Bombay. Classmates remember a kid with spiky black hair who was fond of long bicycle rides, and playing cricket during lunch break.

Young Azim’s plan was to go to Stanford University and graduate with a degree in electrical engineering. It wasn’t necessarily his subject of choice, but, in those years of acute foreign exchange shortcomings, the Indian government only allotted funds to students of “serious” and “productive” subjects, like engineering. But, en route to the US, he planned to first stop off and hitchhike through Europe with friends.

Azim came from a well-to-do Kutchi business family. Apparently, his grandfather was called “The Rice King of Burma”. After the rice trade was nationalised, his family set up a vanaspati manufacturing unit, Western India Vegetable Products Ltd (thus sowing the seeds of Wipro). This was run by his father Hasham Premji, a man so respected for his business skills and probity that, in 1947, Jinnah had apparently invited him to be the first finance minister of Pakistan. The innovative vanaspati manufacturing company was cannily positioned to offer an affordable alternative to ghee, the supply of which, by the 1960s, could no longer keep up with the needs of India’s exploding population.

For Azim, life at 17 must have looked rosy: go to Stanford, get a degree, and work for the World Bank in developing countries (something he had long desired to do). Curiously enough, the idea of joining the family’s thriving vanaspati business doesn’t appear to have figured into his plans. But, as it so often does, life had a googly in store.

Just four years down the road—and one semester short of getting his degree—Azim received a call from his mother. His father had died of a heart attack and he was needed in Mumbai to help with the family business. At first, Azim thought he would be back at Stanford in a few weeks. That was not to be.

There would be testing times ahead for him. At his very first Annual General Meeting in fact. A shareholder stood up and told the 21-year-old he was not competent enough to run the business and that he should sell his family’s stake. That frontal challenge impelled him to start reading books on management—and grow a moustache to look more mature. But for Azim in 1962, all that, of course, was still very much in the future.

Having dropped out of Stanford, Premji is often listed alongside Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Larry Ellison as a member of the celebrity drop-out club. The fact is though, nearly 30 years after leaving the university, he petitioned Stanford to let him complete the remaining credits by correspondence. And when he finally got the degree in 1995, he proudly put it up in his office. Where it still hangs today.