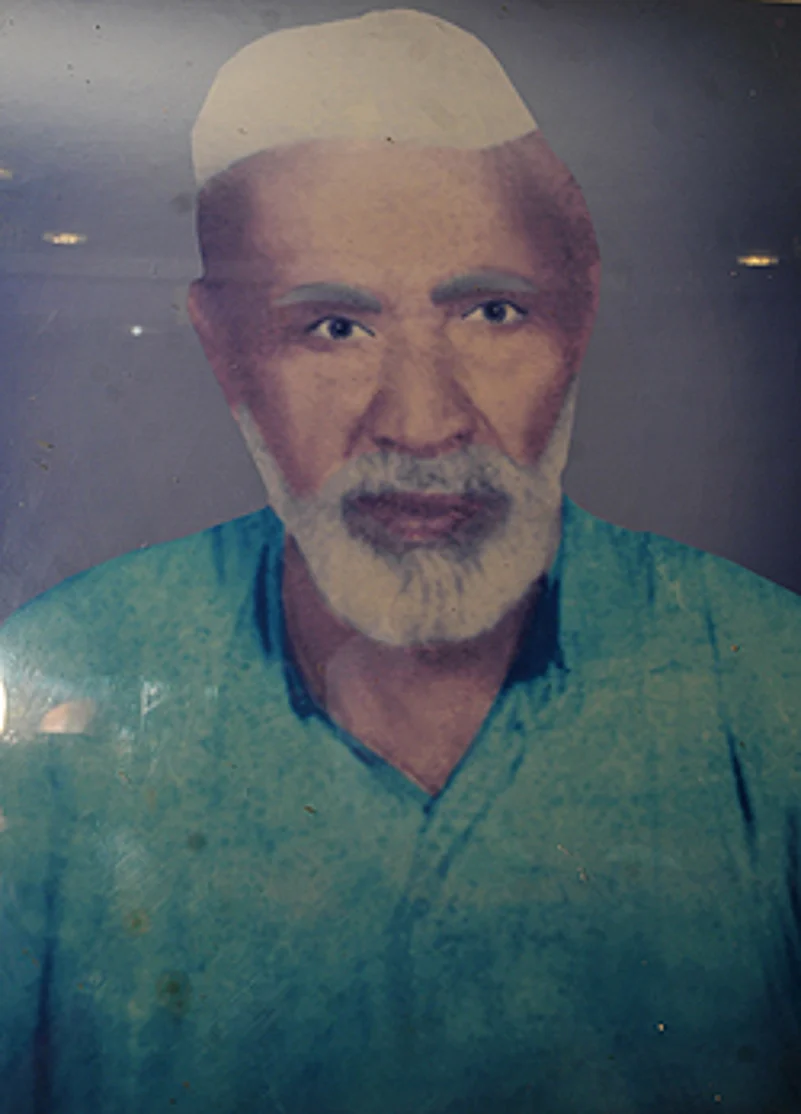

A hundred-and-eight years ago, when Murad Ali (pic left) started his humble kabab-parantha shop on Gol Darwaza street, in the middle of old Lucknow’s busiest marketplace, it was better known for the mujras and tawaifs at its numerous kothas. He earned the appellation of Tunday when he fell off a rooftop in the pursuit of his favourite sport—flying a kite—and had to have his arm amputated. Little did he know that his handicap would lend him and his kababs a brand identity that would outlive generations.

Neither Murad Ali nor his son Haji Rais Ahmad cared to move out of the walled city. The corner at the junction of Gol Darwaza street and Akbari Gate remained synonymous with Tunday’s kababs for a good 90 years.

It was only when Rais Ahmad’s son succeeded him that he started a parallel outlet in Aminabad in 1995. Fifty years old now, Usman, who grew up listening to stories his grandfather would relate to him, recalls how their tiny eating joint thrived from day one. “It was a success story right from the beginning,” says Usman. “I remember dada mian telling us how the place gained popularity with the then cultural elite of the town.”

When Tunday’s was 17, in 1921, ‘sham-e-Awadh’ was the order of the day and nautch girls were an essential ingredient of Lucknow’s cultural ethos. “Members of the royal families were a common sight on the Gol Darwaza street, known for its kothas. The tawaifs here, apart from providing the royals entertainment, often also taught Lakhnavi tehzeeb to the nawabi progeny,” recalls Usman.

His grandfather’s kababs became a special attraction for the royals. However, they preferred to get their orders packed rather than be seen munching on the roadside, which wouldn’t exactly be in keeping with their nawabiyat. Alternatively, says Usman, “the tawaifs, more familiar with the taste buds of their nawabi guests, would send their errand boys to fetch freshly prepared kabab-paranthas; and that was how the business really grew around that time.”

It was around the same year that the British administration decided to stop vehicular traffic on Gol Darwaza street after sunset. As a result, the mile-long street stretching up to the famous Akbari Gate would turn into a walking plaza by evening with stalls selling rose and mogra gajras, and bhishtis watering the road, the evening air redolent with their perfume.

The launch of Usman’s Tunday Kababi Pvt Ltd four years ago marked a new turn in the history of the eatery. But Usman remains very choosy about his franchisees. Which is why Tunday’s has been able to come up only in Bangalore, Varanasi and, more recently, in Patna. “What is important for me,” says Usman, “is that the flavour created by my grandfather in 1904, and well aged by the 17th year, must remain the same even in the 117th year.” Inshallah.