Recently, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M. K. Stalin announced the rechristening of state-run school and college hostels as ‘Social Justice Hostels’. For over five decades, these hostels—maintained by various welfare departments of the state—have made a silent revolution by enabling disadvantaged and underprivileged rural communities to access education.

How A Hostel In Tamil Nadu Is Breaking Caste And Class Barriers Through Shared Meals

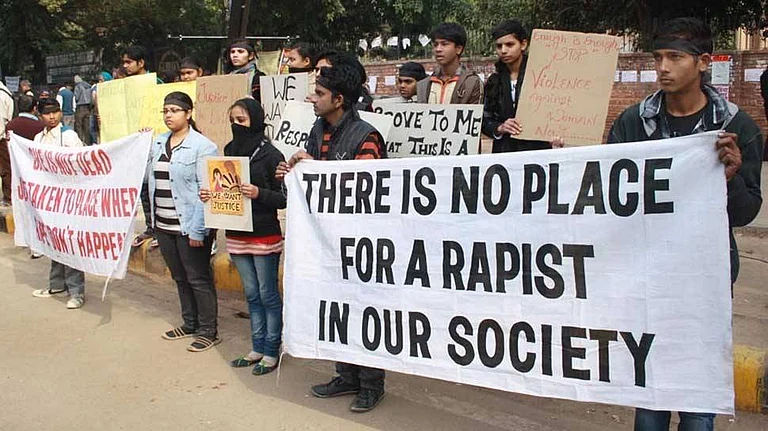

A unique hostel project in Tamil Nadu has brought together students from diverse caste and class backgrounds to live under one roof, share meals and sleeping spaces to promote a new model of social justice.

Compared to initiatives like the Midday Meal Scheme, the free student bus pass, or the more recent Breakfast and Naan Mudhalvan Schemes—in which Tamil Nadu has been a pioneer—the government hostel system for students has rarely received the attention it truly deserves. If the Midday Meal Scheme helped students enter school, the hostel system—generally meant for students from sixth standard through to college and university—enabled them to pursue higher education.

No other state, as far as I know, has a hostel system as well-developed as Tamil Nadu’s, which has now been extended to government educational institutions even in small towns.

During the 1980s and the 1990s, I completed my school and college education while staying in Tamil Nadu’s government hostels, which became a second home throughout my academic journey. Before me, many in my village were able to achieve higher education, thanks to the hostel system. In fact, many of the first-generation government employees from my village had received their education by staying in these hostels.

Among my villagers, the belief still holds strong: a child who studies in a hostel is destined to find employment and move forward in life. For decades, Tamil Nadu’s student hostels have quietly and steadily brought about a revolution in rural and women’s education.

In fact, the scope of the hostel system goes beyond merely educating rural and female children. To me, it is a project in social integration. It brought together children from diverse caste and class backgrounds to live under one roof, share meals and sleeping spaces, and learn an entirely new way of social living—most importantly, it helped them unlearn many of the social prejudices instilled by their families and communities. In this regard, the hostels played a more impactful role than the schools. Perhaps the history of the student hostel system in Tamil Nadu did not begin merely as a welfare state initiative of the post-Independence period. In fact, hostels with similar objectives existed as early as the beginning of the 18th century.

Beginning in the seventh century AD, the discourse of Tamil Bhakti saints emphasised devotional egalitarianism, thereby challenging and defying the imposed social hierarchy in the presence of God. We are given to understand that there existed social integration and a sense of camaraderie among the communities of Bhaktas, or devotees.

Several instances reflect their defiance of social norms and caste rules in order to enter temples and worship the gods. However, the translation of the devotional egalitarianism of the Bhakti into modern social egalitarianism was far from a smooth journey. It was achieved—whatever has been gained so far—through various well-conceived, state-initiated visionary projects, one such being the hostel system.

Alongside the temple entry movement, efforts to gain access to schools also began. While it is unclear to what extent the early gurukula system accommodated students from lower social hierarchies, the schools established by Christian missionaries and the colonial government imposed no restrictions. Colonial records and missionary documents reveal the outraged protests of upper-caste students and parents against the entry of lower-caste students into schools. Refusing to sit with lower castes, many upper-caste students left schools, and parents withdrew their children’s enrolment. The issue was gradually overcome as both the schools and the state remained firm in their stance.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the boarding schools run by missionaries emerged as sites of social integration experiments. Influenced by the Pietist movement in Germany, which, perhaps for the first time in Europe, promoted the establishment of boarding schools for the disadvantaged and enslaved—the Protestant missions opened numerous boarding schools across various parts of South India.

The missionaries soon realised that even making children from the families they had converted to Christianity was a challenging task. The students from lower-caste backgrounds often refused to intermingle with those from castes considered lower than their own.

In school hostels, separate time slots and designated areas were requested for upper-caste children to eat. There were also demands for different glasses and plates to be used for drinking and eating. Outrage erupted when the mission enforced a strict rule that food in the hostels must be prepared by a cook belonging to the lowest caste in the local social hierarchy. However, with the firm commitment of progressive missionaries, this phase too eventually passed.

Soon, the colonial state—partly influenced by the persuasion of missionaries—began to gradually open schools and colleges to students from the lower castes.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some upper-caste communities had successfully promoted and supported the education of their children through mutual support. However, education remained largely inaccessible to others due to a range of social and economic barriers. To address this, hostels for backward and lower caste students soon emerged, aiming to facilitate their access to education.

For instance, the Dravidian Association Hostel (Dravidian Home), established by C. Natesa Mudaliar in 1914, provided accommodation to first-generation non-Brahmin students.

Over time, the establishment of similar staying facilities paved the way for the rise of many distinguished figures across diverse fields. However, caste and economic barriers kept the most underprivileged lower-caste children, particularly those from rural areas, away from the fruits of education.

The present hostel system was conceived and began to take shape in the early 1970s, bringing successive generations of rural students—both girls and boys—to educational institutions in nearby towns. The hostels were the sole hope for rural students in areas without schools or colleges and where transport facilities were virtually nonexistent.

In the late 20th century, these hostels significantly expanded educational access in rural areas. For many rural students, it was their first experience of regular meals, concrete shelter, and access to newspapers in both Tamil and English. When televisions were introduced in hostels in 1998, many students watched TV for the first time. They also gained urban exposure and, most importantly, could focus on their studies with fewer hardships. The hostels continue to play this role even today, despite the expansion of schools and colleges and improved access to transportation.

One of the most important functions of these hostels was not just educating underprivileged rural children as a matter of social justice, but also fostering social integration by bringing together children from diverse caste and class backgrounds to live and grow together.

In recent times, the number of hostels has increased, and their infrastructure has been enhanced. According to current data, there are 2,739 hostels accommodating 179,568 students.

These hostels cater to both girls and boys and to students at both school and college levels. Most of these hostels are funded and maintained by the Department of Scheduled Caste and Tribal Welfare and the Department of Backwards Class Welfare. There are also hostels for minorities and denotified communities. Though these hostels are run by different departments, they generally admit students from all communities, making social integration possible. Even decades ago, the hostels run by the SC and ST Welfare Department had well-constructed concrete buildings designed to accommodate over 100 students. Most hostels, initially housed in rented buildings, have gradually improved over time, with upgraded facilities like desks, tables, chairs, and better provisions for sports and recreation. In addition to periodicals and newspapers, hostels for college students have also been equipped with a library and e-library facilities

In the last two years, the current Tamil Nadu government has inaugurated several monumental structures such as libraries, hospitals, bus stands and more, including well-planned student hostels. For instance, last April, on the occasion of B. R. Ambedkar Jayanthi, the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu inaugurated the new building of the M. C. Raja Boys Hostel for college students in Chennai.

The 10-floor building, constructed at a cost of Rs. 44.5 crore, will accommodate 484 students. Four months earlier, at Presidency College in Chennai, he inaugurated a hostel complex for students with special needs. Built at a cost of Rs. 21.60 crore, the facility includes special features such as tactile guiding surface indicators, Braille boards, emergency calling bells, almirahs with smart locks, and bathrooms equipped with specially designed grab bars. The introduction of the Thozhi Hostels for working women— with safety, affordable rent, and modern amenities—across Tamil Nadu in 2023 marks a new phase in the history of the hostel system in the state.

The July 7 announcement to rename these hostels as Social Justice Hostels (Samooga Needhi Viduthigal) is part of the Tamil Nadu government’s ongoing efforts to eliminate caste markers from educational institutions. Though most of the hostels accommodate disadvantaged students from all categories—with special preference given to targeted groups—they are often referred to by the name of the department under which they operate. For instance, they are locally called SC hostel, BC hostel, and so on. To remove these caste markers—an issue for which the Tamil Nadu government had earlier constituted a commission under retired Justice K. Chandru—the renaming of the hostels has now been announced. These hostels are filled with countless untold stories—of quiet struggles, unexpected friendships, and transformative journeys. They remain true symbols of social justice. Several generations of rural and disadvantaged students remain indebted to the visionaries who conceived and implemented this idea of hostel system.

(Views expressed are personal)

S. Gunasekaran is an assistant professor at the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Tags